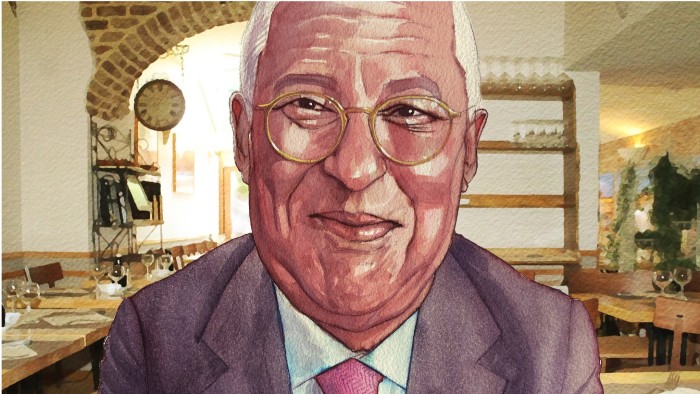

As he squeezes his way through the throng that has packed the entrance of Il Pasticcio with polite smiles and softly spoken apologies, I’m struck by how unlikely a figure António Costa cuts as the man the EU will rely on to face off against US president-elect Donald Trump.

Yet the Portuguese socialist, child of a communist immigrant and devotee of multilateralism, will nevertheless next month assume arguably the toughest job on the continent.

As president of the European Council, he must hold together the EU’s increasingly fractious 27 leaders in the face of a nationalist, isolationist US president who has threatened to slap tariffs on its already creaking economy and strike a peace deal with Russia, its existential foe.

Costa, in dark blazer and pink herringbone tie, flashes his trademark full-face grin when I lay out the vast political, social and cultural gulfs between him and Trump. He takes a breath: “We need to talk with him as soon as possible.”

“Europe has experience of how to live with Trump. Perhaps now he is more radical, more assertive,” he begins. “We need to be prepared for this . . . find a point of trust to manage our differences. If we don’t do this, then it is a problem for the entire world. Not just for us or for him.”

We’re eating together eight days after Trump’s victory. The cosy Italian restaurant, a few minutes walk from the European parliament, is a Brussels bubble stalwart. Costa has been lunching here for more than two decades. Maurizio, the owner, refers to him as “Mr Antonio”. Those standing at the doorway are told it’s a 45 minute wait for a table. Our glasses of prosecco are on the house.

“I’m very curious about how Trump says that with two calls, he can finish the war [in Ukraine] in 24 hours,” says Costa, eyes twinkling behind his orange-rimmed glasses. “I also hope to finish the war in a just way, but ensure a lasting peace, not just for the time of our lunch.”

“Do you believe that he wants to do in Ukraine the same that Biden did in Afghanistan? I don’t believe it,” he says, referring to the chaotic US-led military withdrawal of 2021.

“It’s one thing for [Trump] to look and see Europe versus Russia. It’s different when he looks and sees North Korean soldiers in Russia, and that the main supporters of Russia are China and Iran,” says Costa. “I think it’s impossible for him not to understand this is bigger than Europe and Russia.”

As well as 20 per cent tariffs on imports, Trump has threatened to not defend European Nato allies unless they increase military spending. “But for that, he needs a stronger Europe,” Costa says. “It is not in the interests of the United States to create too many economic problems for Europe because then it will be more difficult to pay for our own defence.”

“Everybody says: ‘Oh, he doesn’t like Germans. He hates German cars’ . . . [But] I think I heard him say that he doesn’t want to engage the United States in new wars,” Costa quips. “So why would he want a trade war with Europe?”

A waitress arrives with a chalkboard. She rattles through the choices but Costa evidently made his mind up 25 years ago on his maiden visit as the guest of Portugal’s then-commissioner Antonio Vitorino. “I always take the speciality [pasta] trio,” he laughs. I take the same, requesting to swap out the truffle ravioli.

Born in Lisbon in 1961, Costa was marked out by his uncle to join the family law firm. He duly graduated with a law degree, but as a member of the country’s Socialist Youth party, harboured dreams to enter politics.

During his first proper election campaign in 1993 for the mayoralty of Loures, a suburb of Lisbon, he organised a race between a Ferrari and a donkey during rush hour to highlight the need for a subway line. The donkey won, and although Costa narrowly lost he gained notoriety and a taste for the game. His uncle’s plans were dashed.

He was elected Mayor of Lisbon in 2007. Eight years later, he won his first of three terms as prime minister.

He says his politics are personal. “I was born when Portugal was a dictatorship, into a family actively fighting the regime. My father was a clandestine communist militant, he was arrested three times. He was also a writer; all his books were censored. My mother was a journalist . . . I remember as a child being at dinner and her receiving a call . . . to fight with the censors.”

At 14, he organised a strike at his high school to protest against the unjustified expulsion of its headmistress in post-revolution political reprisals. He boycotted his exams and was forced to sit the year again.

“It was very decisive on my own political development, to understand the importance of freedom. The end of the dictatorship was not the end of history or the fight for democracy and freedom,” he says. “That’s why I know very well that if you want to preserve freedom and democracy, you need to fight for them every day.”

He will become the president of the European Council on December 1. The role, selected by the EU’s 27 leaders from their own ranks, involves chairing their regular summits, steering the bloc’s political direction and representing it overseas.

With eight years’ experience as a member of the council as Portugal’s prime minister, and well-liked by his colleagues for his pragmatism and sense of humour, Costa was long touted as a likely president.

But the leap from Lisbon to Brussels appeared stone dead a year ago, when Portuguese prosecutors announced a probe into a natural resources corruption scandal with alleged links to his office.

On November 7 last year, prosecutors detained Vitor Escaria, Costa’s chief of staff, and raided dozens of locations including his office, government ministries and the Socialist party headquarters. While asserting his innocence, Costa resigned that afternoon, on the grounds that he could not serve under suspicion of malfeasance.

“I assumed it was all over,” he says. “At that moment, I believed that I would change my life again and . . . go back to university.”

But the case soon unravelled. A mention of Costa in a wiretap transcript was revealed to have referred to a different man with the same name. The investigation is still open but no charges have been brought. His resignation turned out to be a political masterstroke.

“Political life is a strange thing . . . when the [other EU] leaders called me again about the job, I said: ‘OK’,” he chuckles.

But does he believe his reputation is untainted? “I think it’s very clear for everybody in Portugal, nobody talks about this any more,” he says.

The food arrives: two steaming plates piled with orecchiette in a tomato and guanciale sauce, topped with crumbled ricotta, and fresh trofie with pumpkin and sausage. Mine also has risotto with radicchio, while Costa has his plump ravioli covered in shaved truffle.

It’s a moment for me to paint a bleak picture of Costa’s role. At a time of deeply strained national budgets, the EU has been told by former ECB President Mario Draghi it needs €800bn of additional annual investments to revamp its moribund economy. Its ambitious climate change agenda is under heavy political attack. Far-right political movements are gaining ground, and the governments of Olaf Scholz in Germany and Emmanuel Macron in France — the EU’s most important players — are weak.

“Usually, Europe works better in crisis moments,” he retorts between forkfuls. He’s not wrong: the EU’s biggest leaps of integration — from issuing shared debt as a means to survive the pandemic to joint purchases of weapons to support Ukraine — came in periods of acute stress.

“It will be very, very, very difficult,” he admits. “But people are more open-minded, and very realistic about the dimension of the problems.”

He concedes that the EU has a lot of challenges all at the same time. “We need to change dramatically on economic competitiveness. We need to support Ukraine to ensure that we have a just and lasting peace in Europe, we need to fix our relations with the United States, to reset relations with the UK and strengthen our networks with the multipolar world, because the world is more than just the United States, China and Europe.”

Costa’s job will not be helped by the increasing number of nationalists in the council of leaders. Hungary’s arch-Eurosceptic Viktor Orbán used to be the exception in a body dominated by centrists of various stripes. Now he can count Italy’s Giorgia Meloni and Slovakia’s Robert Fico as rightwing allies. Geert Wilders’ far-right Freedom party is the largest in the Dutch coalition government, and far-right parties prop up the ruling coalitions of Finland and Sweden.

“Europe means diversity. We have 27 leaders around the table. All of them with their own national interests, coming from different political families,” he says. “What is extraordinary . . . is that in spite of all of this we move ahead.”

Does the weakness of Macron and Scholz concern him? “It’s democracy working. The members of the council are always changing,” he demurs, pointing to other leaders such as Poland’s Donald Tusk and Denmark’s Mette Frederiksen as providers of stability.

“For instance, you mention Meloni. I always read in the press that Meloni is a problematic member of the council. It’s Orbán, Meloni, Fico,” he says. “What I have seen is always Meloni as constructive. With her own point of view, certainly, but who doesn’t? It’s your job.”

The optimism extends to Orbán too. “Even with Hungary, in the most critical moments . . . we found a way to take a decision,” he says.

A shared love of football partly explains why the Benfica-supporting Costa has a better rapport with Orbán than most. “Orbán as a colleague always has a good personal relationship with the others. Even when we have radically different points of view,” Costa says. “In democracy, the problem is not when you don’t believe the same thing, but when you don’t respect another who thinks differently.”

I ask if he will encourage Orbán, who is Trump’s — and Putin’s — most prominent supporter in Europe, to act as a bridge to the White House.

“I will look to members of the European Council to act as people who can help my job,” Costa says. “It is a smart idea to use the different capacities of the different actors. This current European architecture has not only difficulties, it sometimes also offers opportunity!”

“Look, it’s public: Orbán enjoys very close relations with President Trump. And it certainly helps,” Costa adds. Costa himself has also had extensive conversations with former Nato secretary-general Jens Stoltenberg about how the Norwegian successfully handled Trump during his first term in the White House, he reveals.

I have demolished my food. I could have eaten an entire plate of the orecchiette and its tart, salty sauce. Costa is still working his way through his portions.

Costa’s Indian heritage through his part-Goan father make him the first person with non-European roots to be elected president of any of the EU’s three major institutions. But he has been reticent to talk up this landmark, he says, because he has never made too much of his identity.

“It was never unusual for me in Portugal. The first time I really realised the relevance of my roots is when I was elected mayor of Lisbon, and my photo was on the front page of all Indian newspapers,” he recalls.

“And when I became the first prime minister of Indian origin in Europe, before [Britain’s Rishi] Sunak and [Ireland’s Leo] Varadkar, I was not any more only on the front page of the newspapers, but on all the television channels, the magazines,” he laughs.

He is the proud holder of an Overseas Citizen of India card, given to him personally by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and still has a cousin in Goa. “Now I realise that these roots help me a lot to understand diversity and the world larger than my country and Europe,” he says.

I ask him if he is dismayed at how much the EU’s position on migration has shifted rightward during the past year, with a Polish push to suspend the right to asylum, Italy outsourcing migrants to Albania and Brussels acquiescing to demands from capitals for harsher methods. Costa as prime minister was known for being one of the EU’s biggest supporters of migration.

“On one hand we know that at least for economic reasons, we need to have legal migration . . . [and] we need to ensure that international protection for refugees remains a reality,” he says. “But to protect asylum, to be able to create legal channels of migration, you need to assure the citizens that we are able to control our borders.”

Costa, not for the first time in our conversation, pivots to the personal. “You are British. I am Portuguese. We were born in countries with a colonial tradition. We have the experience of crossing the oceans, to spread, to be everywhere,” he suggests. “We also have a great experience of being an immigrant country . . . both from our former colonies and also other places.”

He recounts an anecdote of an unnamed Polish leader who visited him in Portugal. “He said: ‘Look, António, understand that in Portugal to be or not to be a Catholic is a matter of faith. But in Poland, to be Catholic is what defines our identity and what differentiates us from the German Protestants, the Russian Orthodox and the Ottoman Muslims.’”

“And that’s why this debate about migration is so difficult in the European Council. We all must understand the different cultures around Europe and what that means,” Costa says.

We order espressos. Costa requests his longer, in the Portuguese tradition. As the other diners begin to exit into the grey Brussels drizzle and the staff begin to prepare the tables for the dinner service, Trump looms back into the conversation.

“It’s not only about America. There is a deep furrow in our societies,” he says when I ask about how he interprets the election result. “For different reasons: globalisation, increase of inequalities, poverty, the change of our way of life, a lot of uncertainties . . . it’s more or less the same across all the European countries. So we are more polarised and more fragmented. And this is of course difficult to manage.”

“We need to fill the gap between the European citizens and the EU institutions,” Costa suggests. “I don’t think it’s growing, but we need to narrow it. We need to speak more about the issues that the people care about.”

We’re the only people still left in the restaurant. I pay the bill as Costa jokes with Maurizio about his demand for us to exit with a shot of limoncello. I wouldn’t be averse, but Costa has work to do. Lots of it.

Henry Foy is the FT’s Brussels bureau chief

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FTWeekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen

Read the full article here