Just south of Nashville, Williamson County is a well-to-do enclave, one of the 10 richest counties in the US; actress Nicole Kidman and her husband, musician Keith Urban, once owned a 35-acre ranch there. For almost 14 years, 46-year-old Ashley Williams has also called it home; but she expects to move soon. “Someone I know threw a massive party with cardboard cutouts of Trump, McDonald’s fries and Trump wine,” the marketing consultant says. “I wasn’t invited.” Sixty-five per cent of the county’s voters cast their ballot for the president-elect in November; Williams wasn’t one of them. Now, “my neighbours are sore winners,” she says. The Chicago native is planning a move out of state; her partner’s job was set to transfer him to Switzerland soon, but Williams is keen to switch up her living situation much more quickly, mostly citing concerns about local support for policies such as Tennessee’s near-total ban on abortion.

Almost 1,000 miles away, in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Rebecca Meadows understands the urge to move. The 57-year-old financial executive was born and raised in California’s Central Valley, but has uprooted her family. Meadows and her husband moved to the Midwest a year ago as they readied for retirement. They took a road trip around the country, stress-testing various states and cities such as Houston and Orlando, before settling on South Dakota. Nearby family was one pull factor, as was the comparatively lower cost of living; residents of South Dakota pay no state income tax, while California levies up to 13.3 per cent tax on those who live there.

These weren’t the only factors, though. “We love California, but we no longer felt we were a right fit for it,” she says, “We have very traditional family values, and as a taxpayer, we felt our taxes were not being used in a way that was best. We knew years in advance that’s where the state was headed, and we knew we could not stay.” She’s thrilled with her new home. “The weather and the seasons? I love them,” Meadows says, comparing the year-round balmy climate in Fresno, California with the extremes South Dakota experiences. “People here are so kind, and open to expanding their spheres of friendship, even to someone who’s 57 and relocating.”

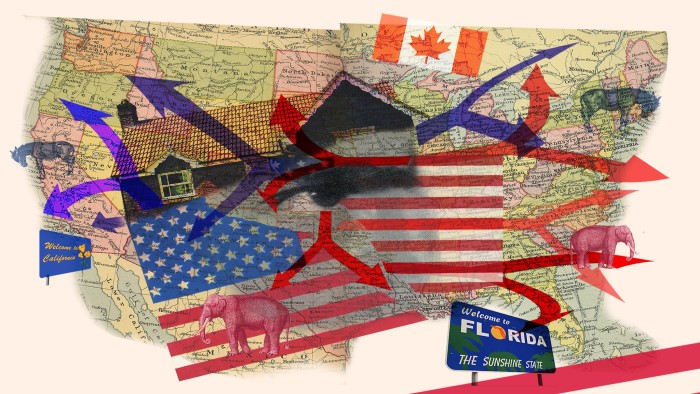

These two women might differ politically, but they share the same impulse: a desire to live somewhere aligned with their values — and their vote. A survey by realtor.com in October showed that almost one in four Americans considered local and national politics a factor in their choice of where to live. Almost 40 per cent said they already lived among like-minded people, and 14 per cent said that their most recent move was to an area where their views would be aligned with the local political landscape.

Just before Donald Trump won his first election in 2016, a Morning Consult/Vox poll showed 28 per cent of Americans would consider moving to another country should he win; Google searches for “move to Canada” spiked 1,270 per cent in the 24 hours after east coast polls closed in 2024 (“move to Australia” surged 820 per cent). Conversely, the 7th Annual Idaho Public Policy Survey, released in January this year by Boise State University, showed a clear rise in right-leaning arrivals to the Republican-controlled state. Thirty-five per cent of longtime residents there identify themselves as Republicans, but 47 per cent of new arrivals do, an 11-point increase over the same survey two years earlier; there has been no similar shift among left-leaning incomers.

1,270%Spike in the number of Google searches for ‘move to Canada’ in the 24 hours after east coast polls closed in November

Amy Stockberger, the South Dakota-based agent who found a home for Rebecca Meadows, says that politically motivated moves have become a core part of her business in recent years. “It’s the freedoms here. The homeless population in the west had gotten so big, the government in those areas allowed the public parks to be taken over,” she says. “We now have an agent on my team from Oregon who helps people like herself make the decision [to move] — based on what the policies were there.”

There are even dedicated organisations aimed at making such transitions as turnkey as possible, such as Paul Chabot’s Conservative Move. Chabot is a former Republican congressional candidate and Capitol Hill staffer who moved with his wife and four children eight years ago from Rancho Cucamonga in California to McKinney, just north of Dallas, Texas. “We realised a lot of other families we met moved here for the same reasons we did, so I thought, all right, why not create a business model around the idea of helping families move out of California to Texas,” he says.

Chabot’s network expanded, and now covers the entire country, focusing expressly on helping clients sell property in Democrat-run states and buy in Republican strongholds. (If you’re in need of a new job, too, he’ll help liaise with Red Balloon, a recruitment company that helps people find work in what Chabot calls “non-woke companies”.) Conservative Move, which acts as a referral platform for real estate agents, analyses data down to a district, allowing clients to cherry pick a home where they’re all but guaranteed to find their neighbours’ views in sync. Still, Chabot emphasises that few people with whom he works upend their lives without pause. “Most people are leaving a place they were born in, where they married. There’s a big psychological impact — it’s never a huge celebration.”

It might seem that such self-sorting is a new, driving force in Americans’ lives. The truth is rather more nuanced, at least according to experts such as James Gimpel, a professor of government at the University of Maryland and author of Patchwork Nation. Gimpel traces the instinct to live among like-minded people to the wake of the second world war. “That’s when we basically managed, at least in the advanced industrial democracies, to solve our most severe problems of material want,” he explains, “so people came by an unprecedented degree of freedom, [which] allowed self-expressive, lifestyle migration to occur.” Put simply, far more of the labour force was now working above subsistence levels, and so had leeway, both economic and emotional, to make proactive choices about their lives.

Gimpel has conducted studies with volunteers where he has shown images of different homes — perhaps a farmhouse with outbuildings, or a sleek town house. As volunteers saw each house, he would describe the community, whether right or left-leaning, and ask for a rating of desirability from 0 to 100. Consistently, both Republicans and Democrats rated homes in the enclaves that reflected their beliefs more highly; when presented with a home in a supposedly Democratic stronghold, Republicans balked most, rating homes significantly lower.

Indeed, Gimpel says, it was the right-leaning populace that was typically more mobile, as it skewed both whiter and wealthier, both factors facilitating more options for a move. Of course, as white-collar voters grow more liberal, he adds, that may well change. “[Humans] are conflict averse, and we don’t really like to feel isolated,” he says.

It was the journalist Bill Bishop who first brought pop culture attention to the concept, with his 2008 book The Big Sort. Bishop looked at county-level voting during presidential elections; since 2004, among the US’s 3,100 or so counties, those where the winner was decided by 80 per cent or more has surged from fewer than 200 in Bush vs Kerry to around 720 this year.

“People go to places where they feel ‘this is me’,” says Bishop, recalling a trip to the suburbs south of Minneapolis where the state Republican party was asking its members to take a poll of their neighbourhoods to determine geographical spread. “They said, ‘We don’t need a poll — just measure the distance between the houses. The closer they are together, the more Democratic the area.’”

Yet perhaps what’s driving such self-sorting is less partisan politics in particular and more governance in general — or how that politics manifests in daily life, rather than simple sloganeering. Stockberger cites the pandemic as a pivot point for her real estate businesses, in particular the stringency of approaches to Covid-19 controls in Democratic-run states. “It was about June 2020 that I saw a big number of relocating clients coming [to South Dakota] because their states were closed down and the restrictions for children were so intense,” she says.

Palm Beach, Florida-based agent Carolina Buia agrees. She works with wealthy incomers from across the country. “Before Covid, we rarely saw a buyer from cities like Chicago, or California,” she says. “A lot of people in California felt they were hindered economically from working, because they couldn’t get their kids back into school. Here we had a hybrid system, where students could choose whether or not to learn online.” She also notes that the new norm of remote working was also fundamental to many decisions to move.

Even if the pandemic and governmental differences from state to state may have sparked some home-selling, it’s still not a mass movement, according to Kathryn McConnell. She is a sociologist at the University of British Columbia in Canada, with special expertise in domestic migration. She cites data showing that internal migration in the US has been declining since the 1970s, with the recession of 2008 particularly impactful. Census data shows that around 20 per cent of the US population moved annually from the late 1940s to 1960s, a period of economic growth and “robust housing consumption”, but that number had dropped to 13-14 per cent in the early 2000s and hit a record low of 8.4 per cent in 2020-21 (even as the pandemic eased, it only climbed to 8.7 per cent the following year).

So-called mortgage-rate lock is likely to constrain that further, she notes; homeowners on a 30-year fixed mortgage, the standard offer in the US, will be cautious about giving up record-low interest rates and remortgaging after inflation has returned. Those who do move usually differ from their immediate neighbours, too.

“We know that [those relocating] tend to be demographically different from the broader populations they move from — in the research world, we call it an ecological fallacy when you assume an individual from a group has the same characteristics as the group,” she says. McConnell also points to so-called “expressive responding” — or what laymen might call venting. Surveying anyone at a moment of frustration is likely to generate the most extreme response. “There’s often a gap in migration research between an individual’s stated migration preferences and the actual migrations they make.”

Certainly, both Ashley Williams and Rebecca Meadows are clear about their motives — and emphatically so. They also have something else in common: neither has given their real name. Both women were happy to be interviewed and share their stories, but neither wished to risk recriminations, social or professional, from those who disagreed with them after disclosing their willingness to relocate for political reasons. Whatever the true dimension, or nature, of self-sorting, no one should have to worry about others finding out their motivations.

Perhaps the Nashville-based woman sums up the febrile mood best. “There’s such an influx of California people here, but the hate they receive on our local neighbourhood Facebook boards is crazy. They have to start a post like this: ‘I moved where I can vote the right way, and that said, where’s the best place to get a haircut?’”

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ft_houseandhome on Instagram

Read the full article here