Islamabad, Pakistan’s military-built capital, had the look of a city under siege on Friday. Shipping containers and trucks blocked the roads in an effort to thwart citizens stirred to action by their support for one man: Imran Khan.

The previous afternoon, the leader of one of Pakistan’s main political parties had walked out of the country’s Supreme Court, sporting his trademark shades and smiling after two days under arrest. The court had deemed his arrest in a longstanding graft case “invalid and unlawful”, and requested that the 70-year-old cricket star turned populist firebrand condemned the violence that had broken out following his detention.

While Khan was in confinement, some of his supporters had clashed with the police and burnt their vehicles, leaving at least five dead across Pakistan. There had even been attacks on army buildings — unprecedented in a nation where the generals sit above politics, but run the show behind the scenes.

During the unrest, embattled prime minister Shehbaz Sharif called in the army to take control in two provinces: Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, as well as in Islamabad. Together these areas account for about two-thirds of the country’s 230mn population. Some social media networks were also partially blocked, to contain the online fury spreading among Khan’s legions of followers.

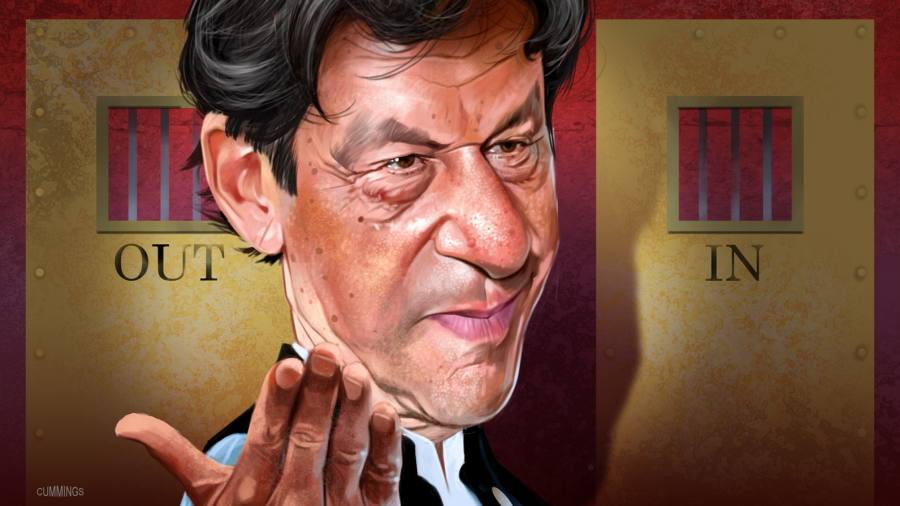

To his defenders, Khan, who survived an apparent assassination attempt in November, is a patriot and unwavering voice of the people. To his critics, he is a dangerous demagogue who is more an agent of chaos than one of change.

An election is planned for this year, in which it is likely that Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party (PTI) will trounce Sharif’s struggling government, which itself ousted Khan last year. The febrile scenes in Islamabad and elsewhere have confirmed his status as Pakistan’s most powerful politician. “In the days ahead, he is going to face a real test of leadership,” says Maleeha Lodhi, a former Pakistani permanent representative to the UN. “First, he has to restrain his supporters, and condemn the violence that took place, and second, if they decide that he still has to answer these charges, then he has to answer them.”

Though he claims kinship with the common man, Imran Ahmed Khan Niazi was born in 1952 to a wealthy family in Lahore. He attended an elite school in Pakistan, and read philosophy, politics and economics at Oxford university. But Khan first came to prominence as a cricketer, captaining the national team from 1982, and to many Pakistanis, he remains a hero for leading them to victory over England in the 1992 World Cup. Three years later, he married Jemima Goldsmith, in the first of what were to be three marriages. When Khan launched his political career soon after, he tapped into nostalgia for his sporting triumph, while channelling public disgust with the industrialists and political dynasts who run Pakistan.

Khan founded PTI in 1996. It won a single seat in the 2002 election, which he took himself. A decade later, he led protesters into Pakistan’s tribal areas along the Afghan border, to protest against American drone attacks. This endeared him to both ordinary Pakistanis and the generals, who appreciated the nationalist gesture.

During his rise to power, Khan underwent a religious awakening and embraced Sufism. He shed his playboy image for good in 2018, when he married Bushra Bibi, his third wife, who he has described as a spiritual leader. In the same year, his promises to fight endemic corruption and poverty brought him to national office in a government that enjoyed army support.

But in 2020, Khan’s political opponents formed the Pakistan Democratic Movement, a coalition that accused him of being beholden to the army and demanded he step down. His own relationship with the military began to sour in 2021, when the candidate he sought to promote as the next army chief failed to secure the post the next year. Khan also disrupted relations with the IMF by announcing a politically motivated fuel subsidy.

Pakistan’s economy was in full blown crisis by 2022, when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine raised the prices of the imported food and fuel on which it relies. When Khan lost a parliamentary vote of confidence soon after the war began, he accused the military and the US of unseating him. Both denied the charge.

In recent months, as inflation has spiralled and Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves have run low, Khan’s own stock has risen afresh. He has led protests across the country, demanding that the next election be moved forward. During Ramadan, the politician was seen outside his Lahore home, squatting on a mat while sharing iftar with his supporters and commiserating about food prices. The nation’s economic crisis is now acute, and Moody’s Investors Service this week warned it could default if it failed to resume its stalled $6.5bn IMF programme.

The corruption case for which Khan was arrested centres around the Al-Qadir Trust, a welfare organisation he and his wife set up in 2018. Pakistani officials have said they are investigating whether the trust served as a front for an alleged bribe from a real estate developer — a claim that Khan rejects. A conviction could bar him from running.

For a leader who built his following on charisma and street smarts, the legal challenge will pose Khan with new tests of his leadership. Pakistanis — facing the threat of further violent unrest — are holding their breath.

Read the full article here