For the past century, educational institutions have used legacy admissions to give preference to family members of alumni or donors, especially their children. Data and various studies show the system has benefited white students most — as intended, because it was originally established to keep Jewish and immigrant students out — even in cases where those admitted to college do not have better grades or higher test scores than non-legacy students.

Related: How college admissions will change in America after the Supreme Court knocked down affirmative action

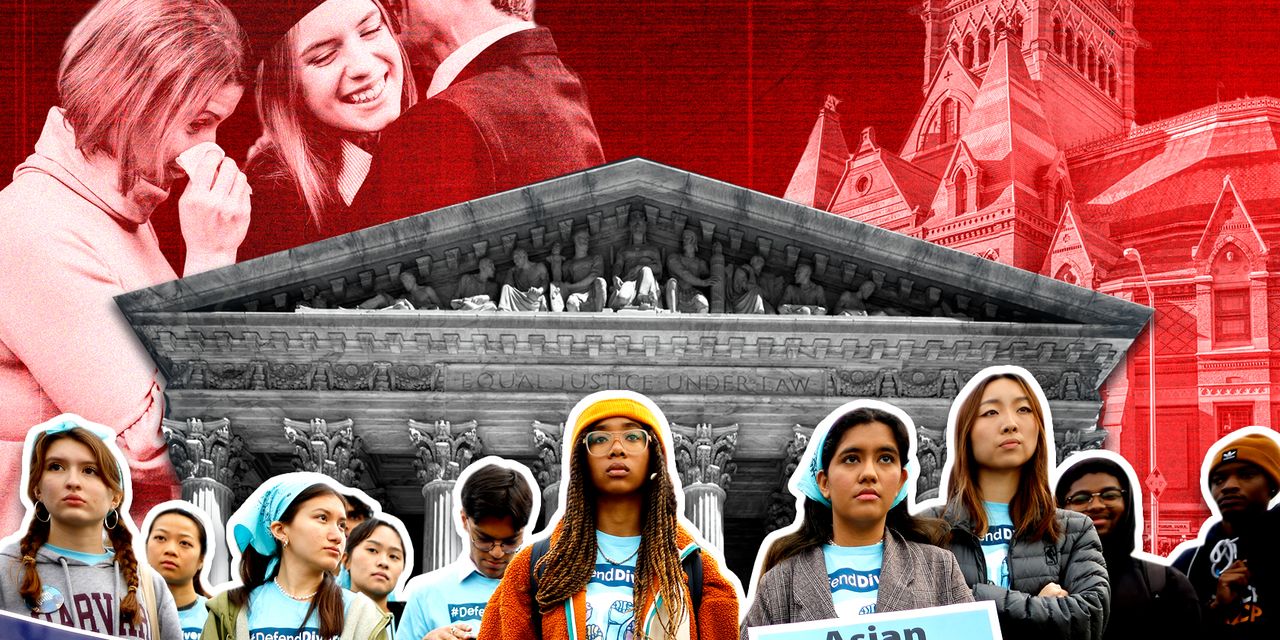

In light of the Supreme Court’s ruling that race-conscious admissions policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina violate the 14th Amendment’s equal-protection clause, the legacy-admissions system may no longer be justifiable either, some critics told MarketWatch ahead of the decision.

And some opponents of the system say it’s unfair no matter what.

Those include the Democratic co-authors of federal legislation called the Fair College Admissions for Students Act, Sen. Jeff Merkley of Oregon and Rep. Jamaal Bowman of New York, who plan to reintroduce their bill, according to Merkley. It would prohibit universities that participate in the federal student-aid program from using legacy admissions, with waivers available to institutions that can show they’re using legacy admissions to benefit historically underrepresented students.

“The longstanding use of legacy and donor preferences in admissions has unfairly elevated children of donors and alumni — who may be excellent students and well-qualified, but are the last people who need an extra leg up in the complicated and competitive college admissions process,” Merkley said in a statement to MarketWatch.

The system “creates an unlevel playing field for students without those built-in advantages, especially minority and first-generation students,” he added.

To Viet Nguyen, the executive director of EdMobilizer, a group of first-generation students who advocate for making higher education accessible and equitable, “getting rid of legacy is a no-brainer,” he said in an interview. Nguyen’s organization supports the federal bill and is also working with states, plus alumni of elite universities, in the push to eliminate legacy admissions.

Still, he called ending legacy policies just one tool in addressing inequities in higher education. “Substantial changes are needed,” he said.

After the Supreme Court issued its decision Thursday, many others also questioned the future of legacy admissions.

“The Supreme Court ended affirmative action today. Expected but disappointing,” Julián Castro, a Democrat who served as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under President Barack Obama, wrote on Twitter. “Now do legacy admissions. They absolutely disadvantage people of color, women and families who have been low-income for generations. They must end.”

Proponents of legacy admissions, such as Harvard, contend the system helps preserve “strong bonds” between the college and its alumni — an argument that is understood to include universities’ desire to hang on to their donors.

But Nguyen said his group is “flipping the script” on that common argument, suggesting that keeping the system in place may negatively affect alumni donations to universities. “We’re saying young alumni will be angry if you don’t get rid of it,” he said.

That sentiment is reflected in various student opinion pieces at universities like Harvard, Brown, Cornell University, Yale University, the University of Michigan and more, which call for ending the legacy system.

Some institutions, such as Johns Hopkins University and Amherst College, have already eliminated legacy admissions, and the University of Pennsylvania appears to be moving away from it. At Johns Hopkins, the move led to an increase in admissions for Pell grant-eligible students, who come from low-income households. Earlier this month, Amherst reported that a record 19% of its incoming students are the first in their families to go to a four-year college.

That bolsters the argument that legacy admissions ensure that “whatever inequalities existed in the past are being recreated in the present by giving preference to those who have parents who were students a generation ago,” said Nancy DiTomaso, a professor of business and management at Rutgers Business School. Her 2013 book, “The American Non-Dilemma: Racial Inequality without Racism,” explored white privilege as a function of white people’s preferential treatment of people in their own networks.

Eliminating legacy admissions would have a “limited effect” on white students and, to an extent, Asian students, DiTomaso said. “There are still many options available from which they can gain a good education and good opportunities for their life outcomes,” she said.

But Black and Latino students have “greater obstacles and lesser resources,” she added, even those whose families are middle class, because of different factors including the effects of policies and laws that have made it harder for their families to build wealth.

From the archives (January 2022): Racial and economic inequality persists. Why do many people deny it?

Read the full article here