Receive free Life & Arts updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Life & Arts news every morning.

For the last few weeks I’ve found myself thinking again and again about the recent cases of orcas ramming into boats off the Iberian coast. It’s a phenomenon that has been happening since 2020 and scientists are still not certain whether the orcas are playing or attacking. I think it’s a fascinating story because the orcas seem to be revealing a new level of agency that’s thrown humans off balance, reminding us that we are not as in control of other life forms as we want to believe.

It’s also intriguing to me because I’ve recently been consumed by reading a book of meditations that has truly deepened and expanded the way I think about our relationship with the ocean and the life within it, particularly the animals. Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals is by American poet, scholar and activist Alexis Pauline Gumbs. She writes as a self-proclaimed “Queer Black Troublemaker and Black Feminist Love Evangelist”, and in this book she considers how the study and appreciation of marine mammal life can inform our attitudes to justice, healing and care for ourselves, each other and the world. In her introductory words, she writes that these animals “have much to teach us about the vulnerability, collaboration, and adaptation we need in order to be with change at this time, especially since one of the major changes we are living through, causing and shaping in this climate crisis is the rising of the ocean”.

It has always seemed invaluable to me to be curious and open enough to learn from sources that challenge our ingrained ways of seeing and understanding the world. Reading Undrowned has made me reflect on beautiful and adaptive ways of living within our changing and increasingly precarious times. This requires us to respect how other animals live and believe that their ways of existing have things to teach us. But it is hard to hold that posture if we are raised in cultures and societies that condition us to believe that animals primarily exist for our use.

In her opening chapter, Gumbs shares the story of the Hydrodamalis gigas, better known as “Steller’s sea cow”, a slow-moving and thickly blubbered creature that was “discovered” in 1741 by a German naturalist. Within 27 years, it went extinct, a victim of human hunting — its demise is thought to be the first known extinction of a marine mammal caused by humans. To be “discovered”, argues Gumbs, is to be put in danger. She ultimately asks us to consider how we can “listen across species, across extinction, across harm”.

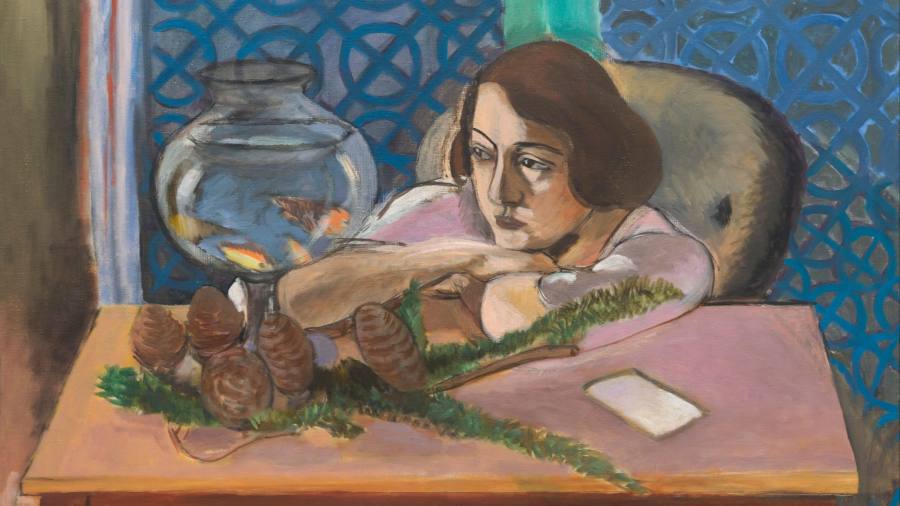

I am taken by Henri Matisse’s 1923 work, “Woman Before an Aquarium”. It is an evocative blend of elements, reflecting Matisse’s interest in painting women, his love of north African and Islamic culture, and in his fascination with goldfish, which recurred in several of his images in the 1910s.

Against a blue textile wall, a woman sits at a desk, her chin resting on her hand. She is staring reflectively at goldfish swimming in a bowl in front of her. Pine cones and branches surround the base of the bowl.

Her melancholy gaze sets a contemplative mood, and the palette of warm browns, mauve and olive gives the canvas an enclosed sense, a world unto itself. It is an interesting painting, beautiful, and almost seductive in how it lulls you to that pocket of space between the woman’s gaze and the captured goldfish. The goldfish, of course, were once taken from their freshwater habitat, and the pine cones and branches brought indoors from field or forest. It makes me think about how often we try to tame nature and control it to suit ourselves.

People have kept aquariums of some sort for thousands of years. But gazing at this painting, I can’t help but wonder if there is some correlation between our domestication of smaller creatures, and our belief that we have the right to capture or kill larger ones. Goldfish do not belong circling glass bowls any more than dolphins or beluga whales, orcas or seals, belong at SeaWorld. It’s funny, sometimes I wonder if there’s also a correlation between shrinking the freedom of what should remain in the wild and the shrinking of our own imaginations.

I have spent a lot of time looking at the image “Capturing a Sperm Whale”, and remain deeply moved by it. I know it as a print by John William Hill, made after the original 1835 oil painting by William Page, which was itself apparently painted from a sketch by Cornelius Hulsart, a whaleman who lost his arm in a whaling accident. Whaling was a major commercial industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the print is a rendering of a sperm whale undergoing a ferocious attack by whalers. The tremendous body of the whale lurches towards the viewer, as it wrestles in distress from the harpoons speared into its sides and piercing its lungs. The dark clouds and the tumultuousness of the ocean seem to match the whale’s flailing despair and suffering. Yet still it fights to survive.

It is a heart-wrenching scene. But besides its ability to convey the suffering of this animal, the image also makes me think of humanity’s age-old antagonistic relationship with the natural world. There remains a stubborn, almost imperialist desire to subdue and control what is elemental, wild and flourishing. And so often in our attempts to do so we end up inflicting harm on ourselves, whether bodily, like in this painting, or upon our imaginations and thinking, and by extension within our own spirits.

I think whatever we do on a small scale does have an impact on the larger-scale things we may not willingly recognise our connection to. This, I imagine, applies to all areas of our lives. The more informed we are, the more consciously we can make decisions. It never ceases to amaze me how a growing awareness and new knowledge about something can profoundly affect the way we think and act and engage with the world.

I love the 2018-19 textile painting “The Ark” by Bengaluru- and Vadodara-based artist Lavanya Mani. The work is influenced by the biblical telling of Noah’s ark and the visual narrative work of Miskin, the late 16th- early 17th-century Indian painter of Mughal miniatures.

Mani’s work consists of two large quilts held together like an open tent by a pole suspended from the ceiling. Both sides of the panel depict a beautiful gathering of animals starting from the top of the quilt and descending to the base, where another circular quilt spreads out like an ocean floor. There are painted birds in the sky, animals among the forests and in the ocean; swordfish and blowfish and manta rays and lobster and hammerheads and seahorses tumble and flow against a blue wall. It is like a gorgeous chorus to non-human life forms, populating the world of the painted textile, and demanding our attention and admiration. Swirling white waves of fabric blending into the sun-drenched yellow sky. The tent-like panels reveal thriving, full worlds on both sides, with not a human in sight.

These animal communities live in an ecosystem that balances itself and supports itself, but which still requires our recognition, respect and care to maintain its equilibrium. One of the aspects of Undrowned that I have cherished the most is how it has reminded me that the ocean is replete with exchanges and communications and an aliveness that we humans barely know the surface of. Seals teach their young that they can breathe in expanded ways that allow them to dive to unimaginable depths. Orcas have the ability to influence other animal life in their part of the water. There is so much happening below the surface of the waters we take for granted. How can we begin to inch out of our own fishbowl thinking and open ourselves to learning about other expanded ways of living?

Follow Enuma on Twitter @EnumaOkoro or email her at [email protected]

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

Read the full article here