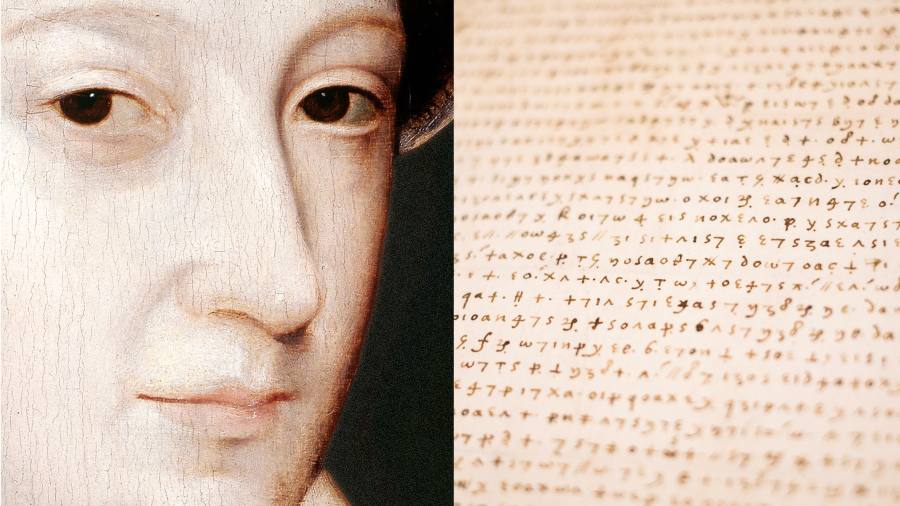

In the spring of 2021, Satoshi Tomokiyo came upon a collection of encoded letters in the online archive of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. They were described simply as Dépêches chiffrées, enciphered messages. Nobody knew who the author was, or who the letters were addressed to. They were written on handmade paper and composed of tightly packed strings of strange, unpunctuated characters, like the writing of an ancient civilisation, drawn with a quill dipped in iron-gall ink.

Dating from the late 16th century, they had been kept for hundreds of years in a volume of miscellaneous letters, bound together in red goatskin for the library of a French noble family, until the Bibliothèque Nationale started digitising manuscripts in the 2010s.

Tomokiyo, a patents expert in Tokyo, posted the enciphered letters to his website Cryptiana, where he collects and blogs about historical ciphers. Two fellow cryptanalysts, Norbert Biermann in Berlin and George Lasry in Tel Aviv, noted the post. Biermann, a music professor, was interested but busy working on reducing the expansive orchestral score of Lorin Maazel’s opera, 1984, for the Regensburg Theatre in Bavaria. Lasry, a software engineer with some time on his hands, set to work. “If somebody hands me a difficult cipher, that’s nasty for me. I have to crack it,” he says.

The only problem was that he kept hitting dead-ends. The library catalogue metadata contained some clues: “early 16th century” and “Italian”. He knew the kinds of enciphering methods used in that era, and tried using Italian, but this didn’t seem to help. He decided to put the letters aside for a while, not uncommon for a codebreaker. Later that year, Lasry remembered the ciphertexts and returned to them with fresh eyes. The Bibliothèque Nationale de France, he thought. I’ll try deciphering it in French. At last, the letters started to unlock.

Lasry began deciphering historical texts during a period of unemployment about a decade ago. The start-ups he was working for had folded one after the other. “I realised, it’s not easy to find a job when you’re 50,” he says. Lasry wanted to stay occupied and use his computer programming skills, so he began solving enciphered texts he found online, first simple ones and then more complex. One day, he came across a website hosting some of the most famous unsolved historical ciphers. He picked a “double transposition challenge”, based on one of the most secure ciphers of the second world war. In November 2013, after two months of work, he cracked it. “There are not many mathematical domains with that eureka moment,” he says. Lasry’s solution made some waves in the cryptography community and caught the attention of an acquaintance, who passed his CV to Google. It hired him.

In February 2022, after managing to decipher most of the homophones — symbols that directly translate to readable alphabetic letters — from one of the letters, Lasry got stuck again. He decided to do something he had tried to avoid for as long as possible. He contacted two of his biggest competitors, Tomokiyo and Biermann. “In the community, we are good friends, but we also compete. Everyone wants to be the first to crack the code,” says Lasry. But this one couldn’t be solved alone; there were simply too many characters to decipher.

A few days after they started working together, Lasry began to suspect the identity of the author. He had uncovered old French words in the feminine form and terms such as ma liberté (my freedom) and mon fils (my son). “Why write ‘my liberty’ unless you are not free?” says Lasry. He told the others he thought they might be looking at some of the lost letters of Mary Queen of Scots, who was executed at the age of 44 at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire, with three blows of an axe.

On November 28, 1570, Mary Stuart — famously tall, auburn-haired, impeccably dressed and dangerously Roman Catholic — rode out of the gates of Chatsworth House in the central English county of Derbyshire, crossing the moorlands and the rocky paths that tangle across the neighbouring hills, and over the border into Yorkshire, on the way to her next prison. She was 27 years old. Her jailer, George Talbot, the sixth Earl of Shrewsbury, was by her side, along with his guards. The prisoner was accompanied by a large entourage, including ladies-in-waiting, her physician, secretary and a personal cook. They reached Sheffield, an early industrial town near ancient woodlands, a few hours later. This was where Mary would spend 14 years, the longest period of her captivity and the longest period of her life in any one place.

She alternated between Sheffield Castle in the valley and the Manor Lodge on the hill, a few miles away on the estate, while the other was being “sweetened” — cleansed of the dirt and sewage that built up without modern plumbing and with large numbers of people under one roof. Sometimes she stayed at Chatsworth, another of the Earl’s properties, and she summered for a while at Buxton spa, in a suite built for her by the Earl. For a jailer, he was, in many respects, attentive to his royal prisoner’s needs. He was perhaps the only person in England who could afford to finance her small travelling court.

Mary had not seen her son, James VI of Scotland, whom she was forced to abdicate to in 1567, since he was a baby. Nor had she heard much news of him in the intervening years. She studied portraits of him, painted by different people, as he grew up without her. Though her complaints were rarely taken seriously, her health was declining and she was plagued by depression. Her swollen legs ached. She had pains in her side. She longed for exercise, which would have helped her condition. But she was not allowed to roam.

She spent much of her day sitting on a crimson velvet chair in her chambers, embroidering, reading, writing in the glow of candles that melted on to gilt chandeliers. Her rooms were luxuriously furnished, the walls bedecked with tapestries and floors softened with expensive Turkish carpets. Her cloth of state, a sign of her queenly status, hung proudly. She washed her face with white wine and retired to a freshly made bed after midnight. Her embroideries were full of emblems and coded language. In her book of hours, a small illuminated manuscript containing psalms and prayers, which she knew was surveilled by others, she signed off her verses as a reigning monarch, R for Regina. In one dated 1579, she wrote:

My fame, unlike in former days,

No longer flies from coast to coast.

And what confines her wandering ways?

The very thing she loves the most.

— Mary R.

What we know of Mary has been shaped by centuries of politically motivated literature, romanticisation and projection. A woman who inherited the Scottish throne at six days old, who was sent to France for safety while still a child, was married three times, widowed for the first time at the age of 17, whose second husband was murdered, probably by her third, who represented in her person the hopes of Roman Catholics desperate to reclaim the English throne and the fears of puritanical Protestants intent on defending the Reformation. Portraits of her can feel tantalisingly real but differ radically: a stern martyr clasping a crucifix, in cap and high-collared dress; a seductive rebel queen capable of bewitching men with her beauty. Shakespeare was fascinated by her, as was Jane Austen.

Mary knew the importance of shaping her own image, even in death. On the day of her execution, she wore a black satin gown and white veil that reached to her feet. As the gown was removed by her gentlewomen and the executioners, the waiting crowd gasped. She stood before them in crimson undergarments, “the liturgical colour of martyrdom in the Catholic Church”, according to biographer Antonia Fraser. It was Mary’s final performance.

Throughout her life, she used ciphers extensively. She would dictate letters at great speed to her secretaries, whose job it was to encipher the outgoing letters and decipher incoming letters using a key. More than a hundred of her cipher tables have been identified in various archives. Her letters, which number in the thousands, allowed her to keep abreast of political news, seek advice from allies in France and exert her will. They were a poor proxy for face-to-face communication, travel or direct action. But, in an era when religious plots were brewing across Europe, they were lethal. William of Orange, the Protestant leader of the Dutch Revolt, was assassinated in 1584 after Philip II of Spain put a bounty on his head. Mary, a figure of both adoration and ire, was considered a threat to the rule of her cousin, Elizabeth I. “So long as that devilish woman lives, neither Her Majesty must make account to continue in quiet possession of her crown, nor her faithful servants assure themselves of safety of their lives,” wrote Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth’s spymaster and secretary, in 1572.

In 1587, Mary was brought to trial for conspiracy. The main pieces of evidence were intercepted letters that showed her involvement in the Babington Plot, a scheme to kill Elizabeth I. On February 8, when her head, detached from her body, rolled towards the crowd, her lips were “still moving as if in prayer”, the British historian, John Guy, wrote in a 2004 biography.

Biermann and Tomokiyo agreed to help Lasry decipher the letters, each working remotely on shared Google Docs from their homes in Germany, Japan and Israel. “Norbert and I looked at the partial decryptions and came up with suggestions for what different symbols could mean,” says Tomokiyo. “It wasn’t the hardest cipher, not compared to, say, something like the Zodiac cipher,” says Biermann, referring to a code made by the so-called Zodiac Killer in 1969. “Here, it was just the sheer number of symbols, and there were a lot of letters.” Over the next couple of days they confirmed Lasry’s initial findings. Then, on the third day, they deciphered the word “Walsingham”. In cryptography terms, they’d hit the jackpot.

To break a ciphertext or identify the type of cipher, codebreakers usually start with something called frequency analysis — studying how many times a character or group of characters appears. But this technique was not useful for deciphering Mary’s letters. Ciphers became more complex during the Renaissance, when the need for encryption grew. A key accelerant was the introduction of resident ambassadors for the first time in Europe in the 15th century, according to Bill Sherman, professor of Renaissance studies at the University of York. Rising literacy rates, the spread of the printing press and the beginnings of the postal service led to an explosion of written communication — and with it the ability of restless nobles, diplomats and spies to share secrets across borders and oceans. To evade detection, cipher-makers turned to evermore sophisticated methods.

Homophones — multiple symbols to represent one letter of the alphabet — were introduced. Another invention was the nomenclator, a small dictionary of symbols that represent words: names, places, parts of words and blanks. Diacritics are glyphs attached to symbols, like accents on a letter, and these glyphs attribute a standalone word or part of a word to each symbol. For example, O, O/, and O* would each stand for a different word, or part of a word. They throw the decipherer off because they look like they could be recurring letters. The use of diacritics is a distinguishing feature of Mary’s ciphers because they were not commonly used until the 17th century.

The ciphers Mary used were exceedingly complex for her time. Lasry, Biermann and Tomokiyo ultimately identified 219 distinct graphical symbol types in the letters, including homophones, nomenclature, diacritics and nulls. The process of deciphering also involves reconstructing the historical cipher key itself, a table of symbols and their meanings that unlocks the readable text across all of the letters. To have the cipher is to hold the key.

“The characters of the cipher symbols are like Greek characters or geometric shapes,” says Tomokiyo. “They cannot be handled by computers so we have to transcribe those symbols into characters that can be read by a computer. That transcription work was very tedious and took many weeks.” They took the symbols they had classified, and applied a “hill-climbing algorithm”, which scored possible solutions based on how good the match was between homophones and alphabet letters. It made use of the fact that certain five-letter combinations appear frequently in French; ision, ement, etles, ourle. The remaining matching had to be done manually. Slowly they decoded one word after the other.

Some symbols continued to throw them. A comma sign, which looked like the familiar punctuation mark, occurred after 18 different symbols. After Biermann analysed fragments of partially decrypted text, he discovered it was in fact a diacritic, meaning that each of the 18 symbols the comma was next to corresponded to standalone words. This was a major breakthrough. They could now unlock the meaning of almost 20 words. There were yet more stubborn symbols, which were not diacritics or homophones, and whose function was unclear. One looked like the number four with a tail, and one looked like a stretched question mark. This time Lasry and Biermann were stumped.

In his day job at a patent firm in Tokyo, Tomokiyo sits in a cubicle on the 16th floor of a concrete high-rise building, preparing applications for clients who hope to prove that their invention is truly, historically, new. “I’m interested in history, especially western history,” he says. “I’m always interested in when history books mention ciphers. I cannot explain why. I like to imagine historical people working on ciphers.” He has broken many codes himself, but he sees his main role as a different one: he aggregates riddles for others to solve.

Tomokiyo runs his cryptology website, gathering and organising ciphers from archives all over the world, like a public service. It is vast, comprehensive, generous. His life’s work is to make sense of the connection between different ciphers. In the process, Tomokiyo is exposed to a lot of historical ciphers. “I am not a good decipherer,” he says. “My colleagues, George and Norbert — they are some of the best in the world, but me, I would say, I am mediocre”. Lasry and Biermann disagree. Tomokiyo possesses a vast historical knowledge of hundreds of different cipher examples and methods to unpick them.

Tomokiyo realised that the character looking like a number four with a tail did not represent a letter. Instead, he says it “dictates a function”: that the preceding letter must be repeated, a technique he had seen before. It was another breakthrough. Eventually, the trio discovered that most of the letters had been written to France’s ambassador in London, Michel de Castelnau Mauvissière. After deciphering the months and years of each, Biermann could date the letters as having been written between 1578 and 1584.

Despite living as a prisoner for 19 years, Mary existed in a perpetual state of hope that her cousin, Elizabeth I, would restore her to the Scottish throne or in joint rule with her estranged son, James VI. In ciphered letter F130 from 1583, she wrote:

Monsieur de Mauvissière,

. . . I cannot thank you enough for the care, vigilance and entirely good affection with which I see that you embrace everything that concerns me and I beg you to continue to do so more strongly than ever, especially for my said release to which I see the queen of England quite inclined. If it brings any success, be assured that I will acknowledge as much as I can your good services with her, and the obligation I have for you from the past.

— Sheffield, this sixteenth of April.

Mary and Elizabeth had a fraught relationship. They never met in person. Mary felt that if only she could speak to her cousin face to face, queen to queen, everything would be set right. They have been depicted throughout history as rivals, despite often referring to each other as sisters. Elizabeth has traditionally been presented as the reasonable, rational one and Mary as emotional and headstrong. Despite Elizabeth being somewhat intimidated by Mary’s famous warmth and charisma, they wanted to meet and almost did in 1562. Arrangements were made, but the French wars of religion and then Elizabeth’s infection with smallpox got in the way. William Cecil, Elizabeth’s chief adviser, saw Mary as a threat to his Protestant aims for England, and put a stop to further plans.

“The thing that gets passed down to us through history,” says the historian John Guy, “is that Mary and Elizabeth were mortal enemies from the beginning because Mary wanted to claim Elizabeth’s throne. It is a load of old cobblers. This is an Anglocentric, religious, partisan take that stuck. When you go back to the original sources, what you find are two relatively young and relatively inexperienced women in a man’s world. You couldn’t win if you were a woman in the 16th century. It was dangerous to marry and dangerous not to. They were the only two people on the planet who knew what it was like to be in the other’s shoes.”

Mary and Elizabeth had to navigate the political and religious influence of their councillors to establish their positions. They were both intelligent and politically astute. In 1561, Elizabeth privately backed Mary’s claim to the English succession, against Cecil’s favoured Protestant candidates, says Guy. Cecil believed religion came first and dynasty second. Elizabeth believed dynasty came first.

Throughout the period of these letters, Elizabeth was looking for some sort of solution to restore Mary to Scotland and protect the idea of monarchy. Cecil had other ideas. He wanted Mary in jail for life or executed for treason. Mary suggested the idea of a royal alliance to rule Scotland alongside her son James VI in 1581 after a visit from Robert Beale, another adviser to Elizabeth. Both he and Cecil thought it a terrible idea, but Elizabeth was in favour. Painfully for Mary, her son did not seem to give her much thought, amid his own growing ambitions.

Mary felt constantly let down by Elizabeth. Over time, the grievances between the two women built. A war of shade was fought between them with quill and needle, through letters, verse and embroidery. Mary’s painstaking encryption of her letters ultimately proved in vain. From mid-1583, Walsingham installed a mole at the French embassy who made copies of some of Mary’s correspondence. By this point, Mary’s tone towards the queen is often harsh. She doesn’t call her chère sœur — dear sister, but ceste Royne — this Queen. She is desperately trying to find a solution for her situation, preferably her return as Queen of Scotland.

In August 2022, Tomokiyo found another volume in the online archive of the Bibliothèque Nationale containing 28 more letters. They looked the same, and they used the same symbols. “It was a disaster, and a big joy,” says Lasry. “We had to make a decision.”

Biermann says: “I remember I was on holiday with my family. And I had to sit at a desk and work on the new letters. I was tired. I was behind on writing my opera arrangement. The orchestra was waiting for the parts so they could start rehearsing.” He complained to Lasry and Tomokiyo about his hands, which needed to be light and pain-free for his piano work, cramping from holding the computer mouse for too long. “Why did you carry on, then?” I ask. “Because,” he says, “it’s Mary!”

Biermann teaches at Berlin’s University of the Arts. On a bright Tuesday in May, I visit him at the music school on Fasanenstrasse. In his practice room, he sits at a Steinway, long limbed and in jeans. Helene, an opera student, stands at the centre of the room, in a linen shirt tucked into mint-green trousers. They begin — Ilia’s aria from Act III of Mozart’s Idomeneo. Biermann paves the way on the piano. Then, Helene begins to sing. Suddenly the room, me, Biermann, the piano, orbit her. She finishes and the room settles. Biermann instructs her — this phrase should be longer, this sound shorter; enunciate this more. They perform again and this time it is even better.

For Biermann, uncovering secrets from centuries-old documents is time travelling. “When you find a historical ciphertext and you have no idea where it will lead you, and then you figure out one word, your foot is in the door of the past. You’re uncovering something that has been unknown for years, centuries.” I imagine his foot sticking through a portal to another world. Music is a coded language that he interprets every day. Deciphering the letters is a way of trying to understand Mary, as if the composition of her life is a score that could one day be heard, her soft voice entering the air once more.

When Lasry, Tomokiyo and Biermann reached the final stages of translating the texts into readable words, they began to fear something every successful code breaker fears — that afterwards, someone would tap them on the shoulder and say: “Hey, those letters you just spent a year deciphering? They’re all known to historians. And the plaintexts are here in this archive.”

To pre-empt this nightmare, the trio attempted to find a match in other archives. “Boom. One of the letters clicked,” recalls Lasry. Would all of them find a match? Eventually, they found only seven letters that appeared as plaintext copies in archives. They all date from 1583 onwards, the time Walsingham’s mole was operating in the French embassy. They were in the clear.

In September 2022, they finished deciphering and transcribing the second volume. They submitted an academic paper detailing their discovery in December. It was published in the peer-reviewed journal, Cryptologia in February 2023. Alexander Courtney, a history teacher at The Perse School, Cambridge, believes the letters “will keep historians busy for years, and help them rewrite parts of Mary’s biography”. Courtney is a scholar of early modern history working on a biography of Mary’s son.

Courtney is the only historian to have seen most of the deciphered letters. They are still difficult to read. Despite Lasry, Tomokiyo and Biermann’s best efforts to edit the letters themselves, they needed help from a historian. They are written in Middle French, without punctuation or word breaks. They contain mistakes. Mary’s secretaries didn’t work flawlessly, and the deciphering process introduced errors of its own. With his knowledge of Middle French, and the historical context, Courtney has been editing the initial decryptions. “The letters are from a spectacular conjuncture of events in British and European history. Everyone knows what happens next,” he says. “Mary is beheaded, the Virgin Queen doesn’t marry . . . England goes to war with Spain.”

The letters give us a sliding-doors view on how the course of English and European history could have been dramatically different if the plans described in the letters were actually carried through — if Elizabeth had married the Duke of Anjou, forming an alliance with Catholic France; if Mary had returned to her Scottish crown. “We have not been able previously to connect up the possibilities that Mary and some other figures in Elizabethan politics saw, for a different ending.”

The letters also contain some psychological insights. Mary would change her tone for each recipient, pull at the heart strings of some, assert her status with others. “She was not a weak, feeble, tragic heroine,” says Courtney. “Mary was a political animal, a guileful politician with a weak hand to play. She was lobbying — lobbying the King of France, lobbying Elizabeth and others through the French ambassador.”

She arranges for the payment of écus — gold coins — to loyal messengers, promises rewards for spies (“Give Fowler ten pounds Sterling on my behalf and assure him that if he continues to faithfully impart to you the intelligence he will obtain from Scotland . . . I could even grant him some annual pension”) and repeatedly asks the ambassador to “please remember to speak to the queen of England on my behalf”. She worries about possible plots against her, attempts to negotiate her freedom, expresses her frustration at delays and misunderstandings.

In a letter written in 1582, between political tactics, we glean a hint of her maternal longings. Mary writes to Castelnau thanking him for a portrait of her son. Compared with earlier pictures, he looks different. She asks to know when and by whom this one was painted, desperate for any detail about her child.

Sheffield Castle, where Mary wrote most of the newly deciphered letters, is now an excavation site. It lies in a north-east corner of Sheffield in an area called Castlegate — a mix of modern apartment blocks, To-Let signs, shops and takeaways. The castle was demolished at the end of the English civil war of the 17th century. It is difficult to picture Mary inside the grey walls, beside a window above the stinking moat. A dig in 2018 unearthed a very particular image of her, the Earl of Shrewsbury and their entourage’s eating habits: “We know, from the enormous number of animal bones found on site, that a colossal amount of meat, probably deer, was consumed by those living at the castle,” says John Moreland, a professor of archaeology at Sheffield university.

There have been other items found at Sheffield and elsewhere thought to have been hers: a silver key, a handbell, a large canopied bed. We can imagine her famously beautiful long hands, turning the key, ringing the bell. There are people continually looking, trying to find out more about who Mary was, what she felt, what she looked like, what she wore, read and ate. They continue to search for the enigmatic Queen of Scots, hoping, perhaps, that with any new information, they might unlock something and, belatedly, set her free.

Imogen Savage is a writer based in Berlin

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

Read the full article here