Receive free Jack Smith updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Jack Smith news every morning.

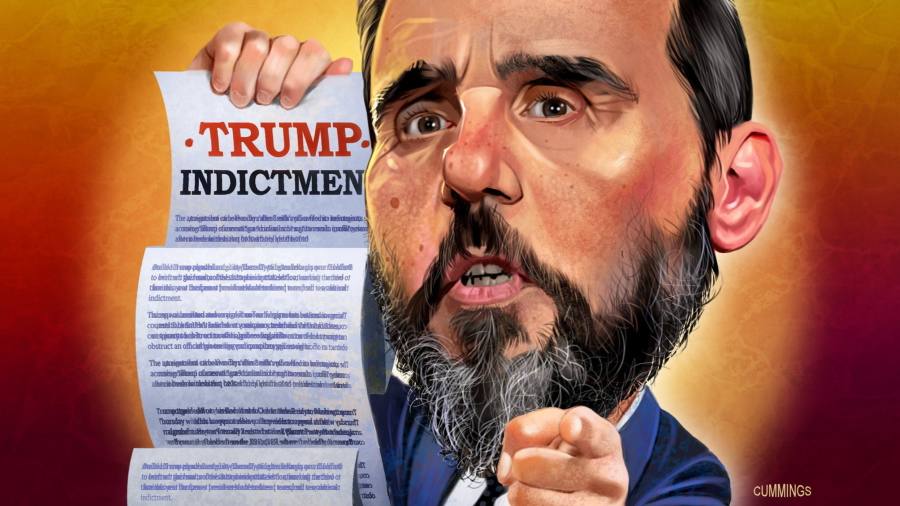

There was a sense of déjà vu as Donald Trump and Jack Smith found themselves together once again in a courtroom this Thursday. It was the second time in as many months that the former US president has been confronted by the special counsel, this time in Washington for allegedly masterminding a “criminal scheme” to overturn the 2020 election.

Trump, previously charged in Miami for mishandling sensitive government documents, sat mere steps away from the veteran prosecutor appointed by US attorney-general Merrick Garland to oversee both investigations. The stakes for the two men could not be higher.

“I can’t conceive of another prosecutor who has come close to the enormity of the challenges that Smith faces in a country that can’t even agree on certain facts and that came so close to the precipice of a violent interruption in the transfer of power as a democracy,” says Ryan Goodman, a professor at New York University’s law school. “This is his burden. And it’s unparalleled.”

Though Smith is seeking speedy trials, the two cases may not be decided before the 2024 election, in which Trump is outpacing other Republicans in the race to become the party’s nominee. Yet the indictments — to which Trump has pleaded not guilty — have already placed Smith in the annals of US judicial history. He “is certainly in a historically unique, historically unprecedented, historically amazing situation”, says Robert Weisberg, a professor at Stanford Law School.

Smith’s sombre demeanour evinces the weight of the moment, his facial expressions — framed by a salt-and-pepper beard — often serious. Born and raised in Clay, a suburb of Syracuse, New York, he attended the State University of New York at Oneonta, followed by a degree at Harvard Law School.

Outside legal circles, Smith, 54, was not previously well-known and the career prosecutor still prefers to stay in the background, keeping public statements to a minimum and taking no questions during brief press conferences. Former colleagues deem him apolitical and Garland has said he is committed “to integrity and the rule of law”. But it was inevitable that the man prosecuting Trump would be thrust into the spotlight, generating support and criticism in equally frenzied fashion.

His backers see him as the official finally bringing the former president to justice after an attack on US democracy. Fan accounts have emerged on social media, while sites sell memorabilia ranging from posters, mugs and T-shirts to stickers with tick boxes labelled “single”, “taken” and “mentally dating Jack Smith”. The National Bobblehead Hall of Fame and Museum, based in Wisconsin, has launched a presale for the “first” bobblehead of the prosecutor.

Meanwhile, Smith’s detractors accuse him and the DoJ of politicising the judiciary and seeking to thwart Trump’s prospects in the 2024 election. A campaign statement this week compared the prosecution to: “Nazi Germany in the 1930s, the former Soviet Union, and other authoritarian, dictatorial regimes.” Trump has called it a “witch hunt” and labelled Smith a “deranged lunatic” and “psycho”, while criticising his wife, who produced a documentary about Michelle Obama and donated to President Joe Biden.

This is not Smith’s first high-profile case. He previously served as chief prosecutor in a special court at The Hague hearing Kosovo war crimes cases. There he indicted former Kosovo president Hashim Thaçi, who has since pleaded not guilty. Legal experts argue such experience has primed him to handle polarising and much-scrutinised investigations.

Smith “appears to be the right person for the moment”, says Goodman. “It shows the kind of intrepid prosecutor who is basically going to apply the law to the facts and not worry about political considerations.”

As head of the Department of Justice’s public integrity section in the 2010s, Smith has also overseen prosecutions of US lawmakers — with mixed results. The unit’s targets included Democratic vice-presidential nominee John Edwards, who was acquitted, and Bob McDonnell, the former Republican governor of Virginia whose conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court.

The charges against him “were completely wrong”, McDonnell told Fox News last week. Smith is “just overzealous”, he added. “I think he doesn’t do an honest look at the law to see if the facts apply to the law and so he’d rather win than get it right.”

Complex cases also defined Smith’s earlier career at the US attorney’s office for the Eastern District of New York. He was among the trial lawyers in a police brutality case that gripped the US in the 2000s and resulted in the conviction of Charles Schwarz, a Brooklyn police officer accused of participating in the rape of Abner Louima with a broken broomstick while in custody.

“I could have chosen anybody I wanted to,” says Alan Vinegrad, lead prosecutor in Schwarz’s retrial and now senior counsel at the law firm Covington. “I chose Jack because of the very strong reputation he had as an excellent trial lawyer: hard working, diligent, thorough, very committed to the cause, serious guy.”

This determination has also found an outlet in endurance sports. As of 2018, Smith had completed 100 triathlons, more than 20 half Ironmans and nine full Ironmans, including the world championship. “Enthusiasm and high energy are key ingredients to a happy life,” he said at the time.

The grit needed for such endeavours is apparently consistent with the prosecutor’s personality in court. He is a “hard-nosed guy”, says Vinegrad. “I would not want to be on the other side of Jack Smith in a criminal case.”

Read the full article here