Lucy Kellaway

FT contributing editor and co-founder of Now Teach

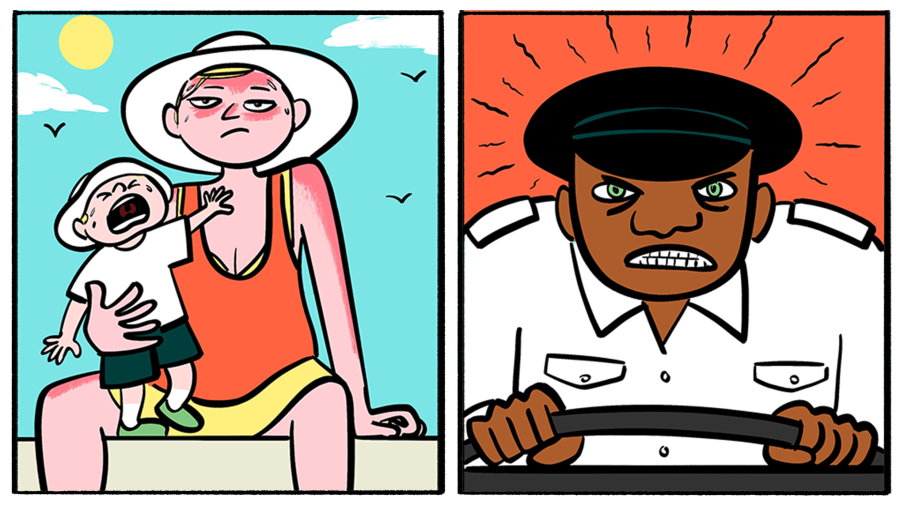

In the photograph I am sitting on a low wall wearing shorts and looking sunburned. On my knee is my daughter, who must have been about one, which means the year was 1992. We are somewhere in Tuscany and we are on holiday.

I’m not smiling — which isn’t surprising, given everything. We had gone away with various couples with young children and had rented a villa where the rooms were dark and the walls thin. All night the babies cried — as soon as one stopped another started up. Every morning frazzled adults dithered inconclusively over plans for that day, so by the time we arrived at Cortona or San Gimignano the heat was intolerable, as were the crowds of other foolish English people.

In the evening we did competitive cooking by rota and when it was my turn I laboured over a lasagne — my technique disparaged by the Italian villa owner, who had popped by to see if we were making a mess (we were). By the time our friends’ children were finally in bed it was 10pm, the lasagne was desiccated and the adults not quite drunk enough not to notice. Someone raised the subject of Maastricht and suddenly they were all shouting at each other. I wanted to shout too: I don’t give a crap about Maastricht! This isn’t fun! I hate all of you! I want to go home!

It wasn’t the worst holiday ever. But it was thoroughly unenjoyable in a way that should have been predictable. Why had I agreed to go away with other families for two whole weeks? Why did I think Tuscany would be nice in August when half the metropolitan elite from London would also be there?

Although I often dislike holidays when I’m on them, I love the idea of going away as much as the next person. According to a recent survey, half the British adults questioned said they lived for their holidays. A third did jobs they hated in order to have money for a holiday that would give them a short break from the hatefulness. Most bizarre of all, a third said that of all the terrible things about Covid, not being able to fly off abroad was one of the worst.

What is this magic allure of a holiday that we can’t do without? For me it’s two things: rest and escape. Yet 60 years’ experience tell me how hard either is to achieve; my best chance of finding them is going somewhere familiar and quiet that I can reach by car. There is no rest queueing for Ryanair flights at Luton or fighting for the last hire car at midnight at some boiling European airport.

Being in a strange place also seems to invite mishaps and involve a disproportionate number of brushes with the emergency services. There was one holiday when our hire car skidded and flipped over and, although no one was hurt, there was endless argy bargy with the fire brigade. Twice we had all our luggage nicked, leading to waits in foreign police stations and at the embassy to get new passports. There was a visit to a French hospital when I had been bitten by a dog and needed a rabies shot, and untold trips to strange doctors in search of antibiotics. Wherever there is a swimming pool there is a miserable child with an ear infection.

Although tiresome, these things alone can’t ruin a holiday. If it is otherwise enjoyable you can forgive unrestful interludes as being part of the adventure.

What is unforgivable is when a holiday fails to provide any escape. For me this is the central flaw in every planned getaway — there is no location far-flung enough to offer escape from yourself. Wherever I go my failings, moods and thoughts come along uninvited. Neither is there any escape from the family and friends you are travelling with as holiday means 24-hour confinement in a way that real life never does.

This was the undoing of that Tuscan holiday. It was nothing to do with heat or sleep deprivation. It was the fact that otherwise serviceable friendships broke under the strain of enforced proximity.

By far the worst holiday of my life was on a Greek island with my husband and children. The Aegean Sea lapped the sand just below the veranda of the simple house we’d rented. We swam in the pale turquoise water and read books and ate in a pretty taverna where the retsina was cold and the feta salty. Yet the perfection of the surroundings provided no balm for a marriage that was in trouble; instead it shone a spotlight on the extent of the dysfunction. Never have I longed so passionately for a holiday to be over so I could escape to the restful routine of everyday life.

Every morning this summer from 6am I can distantly hear the planes taking off at Newcastle airport. Every five minutes another couple of hundred people who have been living and saving for this break hurtle over my house towards their roasting hells in Corfu, Faro and Menorca.

From the cool peace of my own bed I hope they are not too disappointed, they don’t fall out with family and friends and they return renewed. This year, at least, I won’t be going with them.

Martin Wolf

In the summer of 1956, when I was just about to be 10, I went with my parents, my brother and a friend on what turned out to be my worst ever holiday. It was to Loch Lomond in Scotland.

The place was beautiful. But, alas, it rained incessantly. When the rain temporarily cleared, I, my mother, my younger brother (then nine years old) and my friend went on a walk into the hills. My father had returned to work in London.

We left the cottage in the late afternoon. After some time walking, we became separated somehow. I remained with my mother, while my brother and my friend went on ahead — and disappeared.

My mother, with me in tow, tried to find the two missing boys. But the area was far too large. Whether they heard our cries and ignored them or were too far away to hear, we did not know.

After some time, my increasingly worried mother decided to go back. She also must have hoped that the two boys had found their way home. We got back to the cottage at about 6pm. But there was still no sign of them.

By now, my poor mother was frantic and called the police. Then it got dark. Finally, at about 10pm, the two boys turned up.

My infuriated mother hit my brother, which she normally never did. Why, she demanded, had they separated? He explained that he had been trying to get to the top, but each ridge opened up a view to the next one.

After that frightening episode, my mother kept us close to her. Most of the time we were stuck in the cottage as the rain poured down. Finally, almost at the end of the holiday, we had a bright, sunny day and decided to swim. The water was cold, but refreshing. But I cut my foot on a sharp stone. It bled freely.

My parents decided that the British Isles were not for summer holidays. Next summer, they found a flat in Bocca di Magra, a village on the coast of Liguria, in north-west Italy. In the years that followed, my parents rented a flat there, and then, when I became a parent, I rented one with my brother and now we own one of our own in the same village.

Our worst holiday led to our best one, and many more after it.

Stephen Bush

FT columnist and associate editor

When I was 20, I had two plans for the money I had earned selling bad food at Legoland. The first was to visit my grandfather in Zambia, and the second was to go Interrailing in Europe. My cunning plan to do so involved taking a cut-price route to Kenneth Kaunda International, Lusaka’s main airport. There are no direct flights from the UK to Zambia, but the usual route involves a journey to one of Africa’s hub airports — usually in Nairobi or Johannesburg.

However, mystifyingly, it was cheaper — albeit more destructive to the planet — to fly from London to Amsterdam to Dubai before arriving in Nairobi.

The journey there, and the time with my grandfather, went off without a hitch. But my selfishness had clearly angered the planet, and my journey back was disrupted by the eruption of the Icelandic volcano Eyjafjallajökull, which began to ground flights back to Europe as my return flight was halfway to Nairobi. I had a choice: stay in Nairobi for an indefinite period, head to Dubai for an indefinite period or try to make my way back to Europe by any available means. I went for option C, which in the end meant a flight to Egypt, a flight from Cairo to Rome, and from Rome a series of trains and coaches to the ferry at Caen in France.

Travelling while mixed-race is, well, mixed. At best, everyone thinks you’re local: I was greeted as café au lait in France, caramello in Italy, and, to my surprise, as Egyptian in Cairo. But at worst, everyone thinks you’re from whatever the local out-group is: I was abused as Algerian in Egypt and France, and curiously as Eritrean in Italy. I travelled in empty carriages through winding Italian countryside, in a sweltering coach from Milan, and on a ferry that smelt overwhelmingly of stag do from Caen. By the end, I had used almost all of my nest egg. I suppose, in a sense, I did get to go Interrailing — but not quite in the way I wanted.

Bryce Elder

FT City Editor, Alphaville

The low point was when I threw a paper plane at Pete Tong.

This was 2007. I’d been made redundant and was a few months away from becoming a father. My partner insisted I make the most of the freedom, since it would never happen again, but I was broke and lost. My last grasp at being carefree had a travel and accommodation budget of £250.

Several bad decisions later I checked into the cheapest room in the cheapest casino in downtown Las Vegas. The idea was to write something.

But two weeks alone in Vegas is too much. Everything about its immersive artificiality is designed to mainline vices and, not being much of a gambler, I drank. Each day I’d walk to a different bar, write a sentence or two about the fraud at the heart of the American dream, and drink bourbon until being asked to leave.

The evening before my flight home, in a back room of the MGM Grand, the British DJ Pete Tong was playing. In my maudlin state I decided that he was a beacon of authenticity in this vacuous place and needed urgently to let him know, but casino goons blocked all routes to his booth. So I wrote a musical request in my notebook — the kind of obscure, serious tune that would signal he had an ally in the room — tore out the page, folded it into a dart and threw it at his head.

The invitation to leave was unusually forceful. And now, whenever I catch myself reminiscing about life before responsibility, the memory of being ejected on to the Strip, having nearly taken out Pete Tong’s eye, is a useful corrective.

Lilah Raptopoulos

Host of FT Weekend podcast

My family is not an adventure travel family, but one year, we convinced ourselves to take the vacation of our lives: Guatemala. I was 18 and my sisters were 26 and 30, all of us single. It felt like maybe our last chance at a nuclear-family holiday.

My mother planned the trip for months. There were volcanic hikes, scenic car rides, cooking classes, biking tours, maybe a zip line? We packed. We bought adaptors and new digital cameras. The night before our flight, around 8pm, my sister called. In four small words, the dream slipped through our fingers. “Guys, my passport expired.” It slipped through our fingers and straight down a well.

My mother spent that night on the phone, cancelling everything. She booked a last-minute trip to Florida to replace it, renting an old couple’s timeshare in a retirement village. I remember us all meeting at the airport the next day. There was a long pause, and my sister looked at us and said, “Sorry, guys”, and we laughed with rage.

I don’t remember many details of the trip to Florida. I’m sure it was perfectly fine. The condo had decorative shells and pastel art. We probably ate at a few versions of the Joe’s Crab Shack franchise. I also, strangely, hold a memory that my mind invented of the trip that never was: our family, joyfully zip-lining over a Guatemalan rainforest.

It’s been 15 years. Guatemala has travel warnings, my sisters have kids, and we’ll probably never go. But every once in a while, my other sister still turns to me, and whispers, “We should have just gone. We should have sent her to the passport office and gone on that fucking trip.”

Tim Hayward

FT food critic and restaurateur

I’m on holiday at the moment and, as Englishmen abroad must, reading Dante’s The Divine Comedy. It’s remarkable how current it remains. I did not know that the eighth circle of Hell comprised 10 concentric ditches or bolgias, each assigned to a subset of the fraudulent. Bolgias for panderers, corrupt politicians, counsellors of fraud and even one for simoniacs — those who sold favours and offices. This prescient 14th-century genius had foreseen Boris Johnson, Andrew Tate and almost any other contemporary sinner. But even he would have had to dig down to extend. He’d have had to have built a whole 10th basement circle for the people who equip the kitchens in holiday rentals.

I am in the charming southern French town of Uzès. Wine country. Honeyed stone baking in 30C heat. Food writer Elizabeth David came down here in her declining years, took a flat overlooking the twice-weekly market in the Place aux Herbes. Me? I get to stuff my bags with the finest produce and return to a kitchen where there are two blunt ceramic knives. How, you scream, can ceramic knives be blunt? Simple . . . stick a sharpening steel in the block next to them and watch a hundred frustrated holidaymakers send sparks showering into the night.

These look like they’ve been used to open bloody tins. Which is a distinct possibility, as there are relics of an electric can opener in the bottom drawer, keeping part of a wand blender and a wok lid company.

A few years ago I got caught trying to smuggle my own knives on to the “Boden Express” — the London to Avignon train. Is it just, I ask you, that because I’m particular about julienning carrots, I should still be on a terrorist watchlist?

Airbnb has upped the game of shark rentiers. Everything looks great for the website. Stacks of fresh ecru towels on every beige surface. Fresh off-white paint. Also three incomplete coffeemakers, eight opened pots of paprika, three half-empty bottles of organic olive oil and a tub of Vegemite in a bedside drawer. There is one napkin/tea-towel curated to match the table linen rather than for absorbency. The crap oven has a pass-agg little note taped to it saying that if I sully its interior, I will incur a €100 cleaning surcharge as “the cleaners are very busy”. I want to heat up a tian, not puke in a cab.

Last night, in front of my own family, I did the trick of getting the cork out of a wine bottle with a wall and a deck shoe. I haven’t done that since art college and hoped I’d never need to again. But then, I believed that when I was a grown-up, there would always be a corkscrew that worked.

Not four that didn’t.

Robert Armstrong

Starting a family? Remember this phrase: “It’s not a vacation; it’s a family trip.” I can’t remember what hardened veteran of the parenting wars passed this mantra on to my wife and me, but it proved a crucial support as we raised our twins. It’s not that small children make your holidays hell. The hell comes as a result of believing, in the face of all experience and evidence, that you, parent of small children, get a holiday at all.

What you get, instead, is a family trip. One primary family trip activity, as all parents know, is touring the emergency rooms of sunny destinations. Do you know how ear infection treatment protocols vary, regionally and internationally?

I do, and you, parent-to-be, will soon know it, too. And ear infections are low on the family trip illness difficulty scale. I will not soon forget the trip on which both of my children, aged two or three, got hand-foot-and-mouth disease, a nightmare of screaming, Popsicles and pink antibiotic liquid.

On family trips, as on vacation, you go and see the sights. But one does not do this because the sights are worth seeing. One does it because it tires out the children and fills the hours before it is appropriate for the adults to drink heavily. If you start to drink early in the day, who will drive to the ER?

My wife and I used to consolidate our family trips with those of her brother and sister-in-law and their three children. The idea, I think, was that there were economies of scale in child care. This may have been true. But, in retrospect, I suspect these benefits were outweighed by the fact that the ability of children to get into greater mischief as their numbers increase is not additive but multiplicative.

I remember a family trip to Wales when four of the children went running straight for a seaside cliff, the drop-off invisible until the last moment. Only last-second hysterical screaming by the fifth child stopped the worst from happening. All four parents — watching the whole thing, helpless, from several hundred yards away — suffered simultaneous nervous breakdowns.

Best of luck hiring local child care. I remember leaving the kids on the third floor of the Airbnb with two babysitters, almost ready to head out for dinner. Then our niece, 18 months old, came tumbling down the winding staircase towards the concrete floor of the front hallway. Her father just managed to stop her on the last step. We decided to stay in and let the hire-a-nannies go.

Why, in those early years, did we attempt holidays at all? That’s easy. Making a chaotic, filthy, deafening home life seem normal was worth the price of the plane tickets.

Jemima Kelly

FT columnist

Our five-and-a-half-hour bus ride from Kigali to Bujumbura had been going just fine until a man at the front, who was late for work, asked the driver to speed up. I had even begun to enjoy the journey, now that we had got over the Rwandan border into Burundi, had entered lush rainforest, and were making good progress towards our beach retreat.

We would be staying in a hut looking across to the Democratic Republic of Congo at the edge of Lake Tanganyika, which I had been excited to discover we would be sharing with the famous Gustave, a 20-foot, 2,000-pound crocodile rumoured to have killed as many as 300 people.

The problem was that the driver, who had seemed in good spirits until this point, did not appear to appreciate being asked to speed up — not one bit, in fact. He seemed somehow offended by the request. We watched in horror from the back of the bus as his demeanour turned to rage: gesticulations, shouting, and then foot flat on the gas.

“Buhoro, buhoro! [slow down, slow down!]” my sister shrieked in her best Kinyarwanda as we barrelled round a blind corner. But this, unfortunately, only served to wind the driver up further, and he seemed to want to show us: keeping his pedal to the metal he now lifted his hands off the steering wheel and threw them in the air. I gripped the back of the seat in front of me as we ploughed through a village, terrified mothers grabbing their children out of the way of the careering bus.

We arrived at the Bujumbura bus station with legs of jelly and dripping sweat, to be greeted by swarms of mosquitoes and ominous thunder clouds. I spent the next four days looking out for Gustave, reading about the horrors that King Leopold of Belgium brought to what is now the DRC, and thinking a lot about our journey back to Kigali.

Madison Darbyshire

FT US INVESTMENT CORRESPONDENT

I have one superstition, and it is that Rome is where relationships go to die.

My relationship perished there, on a romantic mini break. But it became a superstition when friends would tell me: I just had “your” trip to Rome. Meaning, they went to Rome and returned with a smouldering husk of a romance.

The trouble with Rome is that it is a city designed to be in love in. And when you’re not in love, it feels obvious.

When all you have to do is wander through piazzas and gaze at cathedrals, eat four gelatos a day and languish over marathon meals, it is apparent when you’ve run out of things to talk about beyond what you can see.

The sound of forks scraping spaghetti from plates felt desolate as we discussed the couples at other tables — a lifetime away from when he had kissed me outside a hectic train station at midnight, and we could have been the only two people in the world.

At dinner on our final evening, he took me to a restaurant where he had celebrated his birthday the year before. We had the same waitress, they exchanged witty repartee in Italian that I didn’t need to understand to understand. They looked so cute together. He made her belly-laugh. I found myself wishing he would have the courage to ask for her number. It simultaneously occurred to me that this is not what you are supposed to want for the man you are dating.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Read the full article here