Roma Caput Mundi

About fifteen years ago I was making a facsimile of a 16th-century illuminated codex for the publishing house with which I was collaborating, and this codex was housed in the Casanatense Library in Rome. For a few months I went to the capital quite often, checking the fidelity of the reproductions to the original, and each time I stopped for lunch. Although I am almost a vegetarian, I love carbonara very much, and every now and then I make an exception to the rule. Also, because Rome is the world temple of this dish.

Some Roman friends had pointed me to a typical trattoria near Campo de’ Fiori, where I happened to meet a regular customer, a “good fork” as we Italians say, who authoritatively explained to me that Rome’s two most characteristic pasta dishes, carbonara and “cacio e pepe,” have one ingredient in common that is not written in cookbooks: water. (I felt like Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate when Walter Brooke tells him, “Just one word. Plastics!”).

What the Hell Is Water?

Yep, the water. I had always focused on the ingredients, procedure and timing, I had never paid attention to this seemingly non-ingredient of fundamental importance to the success of a carbonara. It is the water that softens the egg and keeps it from “scrambling;” it is the water that makes the crema form and makes it so delicious…

But what the hell is water? as the fish wondered in David Foster Wallace’s famous speech. Water is a vital substance that in its liquid state has volume of its own, but takes on the form of the vessel that contains it. Yet water, and its “liquidity,” serves as a metaphor: in addition to natural liquidity there is economic liquidity. The natural one is the basis of all known forms of life, while in finance, investments that can be immediately converted into cash without capital loss are defined as liquid. Economic liquidity gives life to our portfolios.

Obviously, it is through liquidity that we can fulfill our financial commitments and enjoy the pleasures in everyday life, but I personally believe that financial liquidity is a vital non-ingredient for the health of my portfolio. Although my investments comprise mainly CEFs and ETFs (as well as a couple of BDCs and an ETN), I have always felt that an adequate liquidity component can help me manage my relationship with the financial markets and their manic-depressive phases with more peace of mind. It is a non-ingredient that gives balance and completes my portfolio, like water in carbonara.

I would like to focus here on the two instruments that I use as a cash reserve, to be used at the appropriate time for new investments or simply kept as a “lung” in case I need it. Since I do not like to buy individual T-Bills, on which I am not well versed, I have selected two ETFs that allow me to park liquidity and at the same time earn a small yield to offset the loss of purchasing power due to inflation, thanks in part to rising interest rates.

SGOV and BIL

In my last article, containing an August check-up of my portfolio, I described how the cash from the recent easing of my positions in JEPI and XYLD has been temporarily parked in (SGOV) (iShares 0-3 Month Treasury Bond), an ETF that offers vanilla exposure to ultra-short-maturing fixed income securities of the U.S. Treasury market. SGOV is not the only ultra-short ETF I use in these cases, alternating sometimes with (BIL) (SPDR Bloomberg 1-3 Month T-Bill), which also provides exposure to publicly issued U.S. Treasury Bills that have remaining maturities between 1 and 3 months.

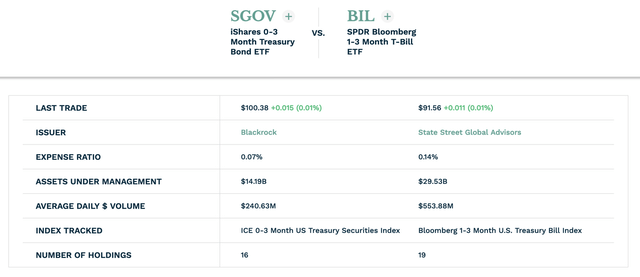

The table below summarizes the characteristics of both ETFs:

ETF.com

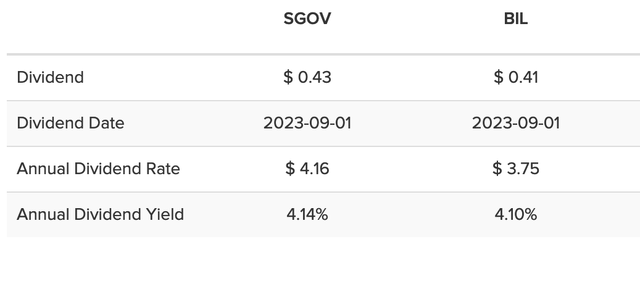

As you can see, the expense ratio for SGOV is half that for BIL. Instead, we can see below the annual yield of both ETFs, with a fair advantage for SGOV, also due to lower costs. In my view at a time like this, despite still high inflation, their dividend yields slightly above 4% make them a good instrument in which to park cash waiting to be invested, as opposed to the non-interest-bearing cash in my bank account.

ETF Database

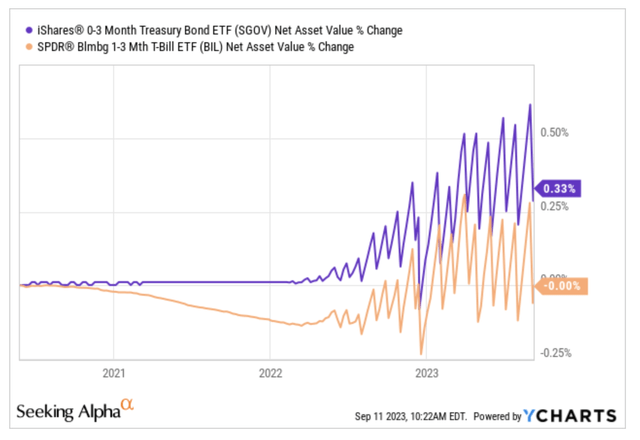

Both SGOV and BIL are a safe tool for short-term investing, capital preservation, and more importantly, liquidity. My preference, however, goes to SGOV, given also the slightly better performance over the past three years, since SGOV’s launch on May 26, 2020. (Moreover, SGOV quotes just above $100, which makes any kind of calculation easier.)

YCharts

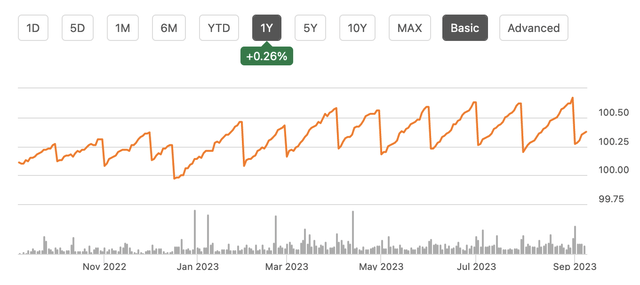

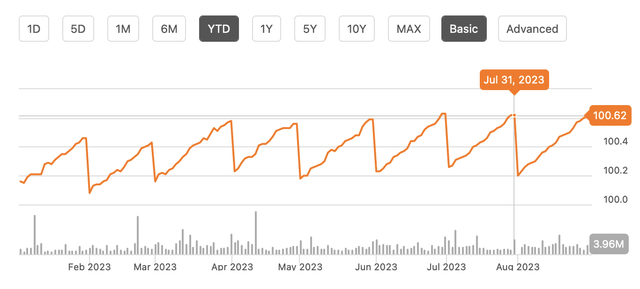

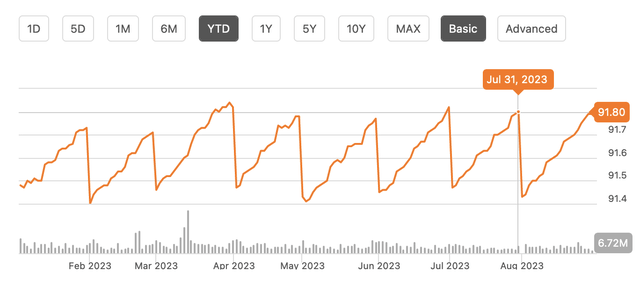

Now, however, since both of these securities have a monthly distribution of varying magnitude but with an ex-dividend date always on the last business day of the month, the sawtooth pattern we see in the graph hints at how their price varies in a constant and predictable way at the moment of dividend payment at the end of each month.

Viewed more closely, SGOV’s graph for 2023 in fact looks like this:

Seeing Alpha

This circumstance prompted me to develop a trading strategy on these ETFs so as to:

- Being able to use them as a parking lot of (almost) tax-free liquidity, while waiting to clarify my ideas on how to invest it;

- Increase the number of trades in order to meet the parameters required by European regulations for maintaining a professional investor qualification.

The Tax Regime

For me, who am Italian, American ETFs are non-tax-harmonized instruments on whose dividends we Italians are subject to a withholding tax of 15% in America and 26% in Italy, for a total amount of 41%. In this case, however, the Italian-American treaty to avoid double taxation provides that the 15% withheld in America can be recovered in Italy at the time of the tax return.

For non-tax-harmonized instruments, during the spring, the bank with which the investor has the securities deposit account provides him with a certification regarding the tax regime of the financial income earned in the previous tax year, indicating the income and the related withholdings (at least, my broker does.) This summary shows the foreign tax incurred, which is to be reported on line RN29 of the tax return as a tax credit already paid on income earned abroad.

On capital gains, on the other hand, we have only the Italian withholding tax of 26%, because they take place in Italy, and of course there are no foreign withholdings. In practice, the final taxation is still always 26%, but in the case of dividends, the time for recovery of the 15% withheld in America is deferred until the following tax year.

Capital Gain or Loss?

This circumstance has prompted me to adopt a strategy of buying and reselling these ETFs monthly, not collecting the dividend and benefiting from buying them back at a lower price on the day after the ex-dividend, which is always the first day of the month. In this way, since the price of any security falls roughly (but not exactly) by the value of the dividend on the ex-dividend day, by selling it the day before and buying it back the day after, I avoid leaving the 41% tax on the street, while collecting the (always positive) difference between the purchase and selling price.

However this strategy, which allows me a secure dollar gain, exposes me to two possible scenarios from a fiscal point of view, related in this case to the trend of the dollar/euro exchange rate, namely:

- The dollar rises relative to the purchase exchange rate. I incur the 26% tax on the gain in euros between the time of purchase and the time of sale (regardless of the gain in dollars), which I will bring to my tax return.

- The dollar falls relative to the purchase exchange rate. I record a loss between the euro amount paid at the time of purchase and the amount collected at the time of sale, again regardless of the gain in dollars.

The best scenario is obviously the second one, that is, the one that allows me to collect the difference between the sale price and the repurchase price (always positive since the beginning of the year, as seen from the previous graphs) but not pay taxes on it because the dollar has fallen against the euro.

This negative difference, or capital loss, is recorded and can be carried forward with a time limit of five fiscal years, during which it can be offset against other financial instruments such as individual stocks, ETNs or certificates (which I do not use, however.) In this case for me, however, it is a “virtual” loss because SGOV and BIL are just a temporary parking lot of dollars waiting to be invested, and I have no intention of converting them back into euros. Even if I could not offset these losses, the damage would be minimal.

A Bet on Euro/Dollar Exchange Rate

The calculation of the difference, whether positive or negative, is made on the basis of the euro-dollar’s reference exchange rate, which is set in concert by the major central banks and announced daily by the Bank of Italy at 4 p.m. Italian time (the so-called “fiscal exchange rate”). All buying and selling euro-dollar transactions made up to 4 p.m. are fiscally settled according to the previous day’s exchange rate, while those made after 4 p.m. are settled according to that day’s exchange rate.

By seeing the movement of the real exchange rate during the course of the day, one can guess with sufficient approximation whether the exchange rate for the day, reported at 4 p.m. and valid until the same time the next day, will be higher or lower than the previous day’s rate. Thus, if, for example, I buy a security this afternoon and the dollar goes up until the close and throughout the following morning, I can decide to reset the position in the first half hour of the market opening (for me, between 3:30 p.m. and 4 p.m.,) with no gain and tax, while waiting to see if the exchange rate is likely to settle. It is true that you pay buying and selling commissions twice, but they are now pocket change at any bank or broker.

As for the taxation of any capital gains realized on currency transactions, Italian regulations stipulate that it is due only if, in the calendar year, the total amount of all currency deposits and current accounts held exceeds 51,645.69 euros for at least 7 continuous business days. Therefore, to avoid taxes, it is enough to be careful with the timing so that you always have lower deposits (or even higher deposits, but for a period of less than seven working days.)

Squaring the Circle with SGOV

Basically, I act like this, taking the month of July 2023 as an example. On July 31, the day before the ex-dividend date, SGOV stock was trading at $100.62, and I sold.

Seeking alpha

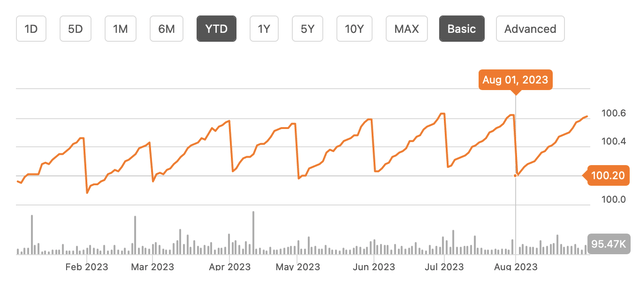

The next day, the ex-dividend date, I bought it back at $100.20 and kept the difference in my pocket. As far as taxes are concerned, what I just said about the euro/dollar exchange rate on the days I made the transactions applies.

Seeking Alpha

As can be seen, the charts account for the subsequent rise in August, which came all the way up to 100.62 on Thursday 31, the day I sold. The subsequent opening at 100.26 on the morning of Friday, September 1, discounted the dividend and I bought back.

Same Strategy with BIL as Well

Of course, I could have conducted a similar trade on BIL as well. Again, taking July 2023 as an example: on July 31 (the day before the ex-dividend,) BIL stock was trading at $91.80, and following my strategy would have been the time to sell.

Seeking Alpha

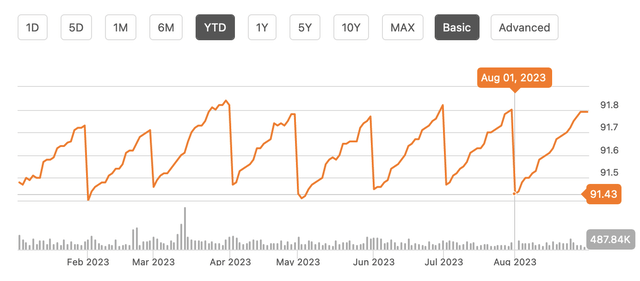

The next day, the ex-dividend date, again following my strategy I could have bought it back at $91.43 keeping the difference in my pocket.

Seeking Alpha

Operability Required by European Regulation

Among the prerequisites for applying and maintaining of professional investor qualification, European regulations require the execution of transactions of “significant size” with an average frequency of ten transactions per quarter on administered savings instruments such as stocks, ETFs, certificates, bonds and covered warrants. In Italy, the administered savings regime covers the case where the investor entrusts his or her savings on deposit to an intermediary, but without delegating the management of the savings.

Of course, while waiting to clarify my thoughts on new investments aimed at increasing the profitability of my income portfolio, I could also secure the required operations by trading with CEFs or ETFs already in my portfolio. However, their volatility would expose me in the short term to the risk of losses both in dollars and in the euro/dollar exchange rate.

Trading on ETFs such as SGOV and BIL avoids the risk of losses in dollars (where indeed the gain is certain, at least in this period of high rates) leaving me to manage only the risk of having to pay capital gains taxes if the euro/dollar exchange rate varies in favor of the dollar between the time of purchase and the time of sale.

Bottom Line

While my strategy of buying and reselling SGOV or BIL once a month allows me to increase (albeit marginally) my dollar liquidity, it also provides me with the opportunity to ensure that I have the number of trades necessary to meet the parameters required by current European regulations for maintaining professional investor qualification, subject to annual review.

All these transactions are conducted by me pending clarification of more profitable uses, although I like to maintain a liquidity buffer at all times, and all in all, it’s better if it’s fruitful. Financial liquidity is like water in carbonara: one of those “secrets” that no one tells you. To make carbonara you need plenty of water over and over again. It is the dish itself that asks for it.

A non-ingredient such as financial liquidity does not appear in the “securities depository,” but it allows me to better create and manage my investment portfolio, providing balance to all its elements and sound sleep to the owner. It is the portfolio itself that asks for it.

Read the full article here