When most couples split up, sleep in separate bedrooms or spend time apart and then decide to get back together, they might go to couple’s counseling or air their grievances in a backstreet coffee shop as a last-ditch effort to repair a once fruitful and happy relationship.

Successful conscious re-couplings typically have one thing in common: Both sides need to change. After all, a professional relationship — just like a personal relationships — is a two-way street. So why has this not been part of the contentious debate on the return of remote workers to the office?

How did it all go so wrong? What’s missing from this picture? How did what started as a “perk” and a safety measure — that was not afforded to millions of service workers during the pandemic — turn into such a PR disaster for companies and an employee-management standoff?

“Aren’t all relationships, professional and personal, a two-way street? Don’t both parties need to change?”

In a relationship when separated couples get back together, they put a concerted effort into both parties’ actions, said Tessa West, a New York University social psychology professor with an interest in workplace behavior, and author of “Jerks at Work: Toxic Coworkers and What to Do About Them.”

Companies need to communicate what’s at stake for both the employee and the employer, she said. “They aren’t going to grow at work, develop new skills, network in a way that will improve the chances that they can get promoted and climb up, [unless they] feel invigorated at work,” West added.

Before the pandemic, we were often mired in the minutiae of everyday office life — just like we are in domestic relationships: The photocopier is jammed. The printer is printing out paper on another floor. Someone borrowed my iPhone charger, and didn’t bring it back. You’re on mute. That’s all changed. Bigger cracks have appeared.

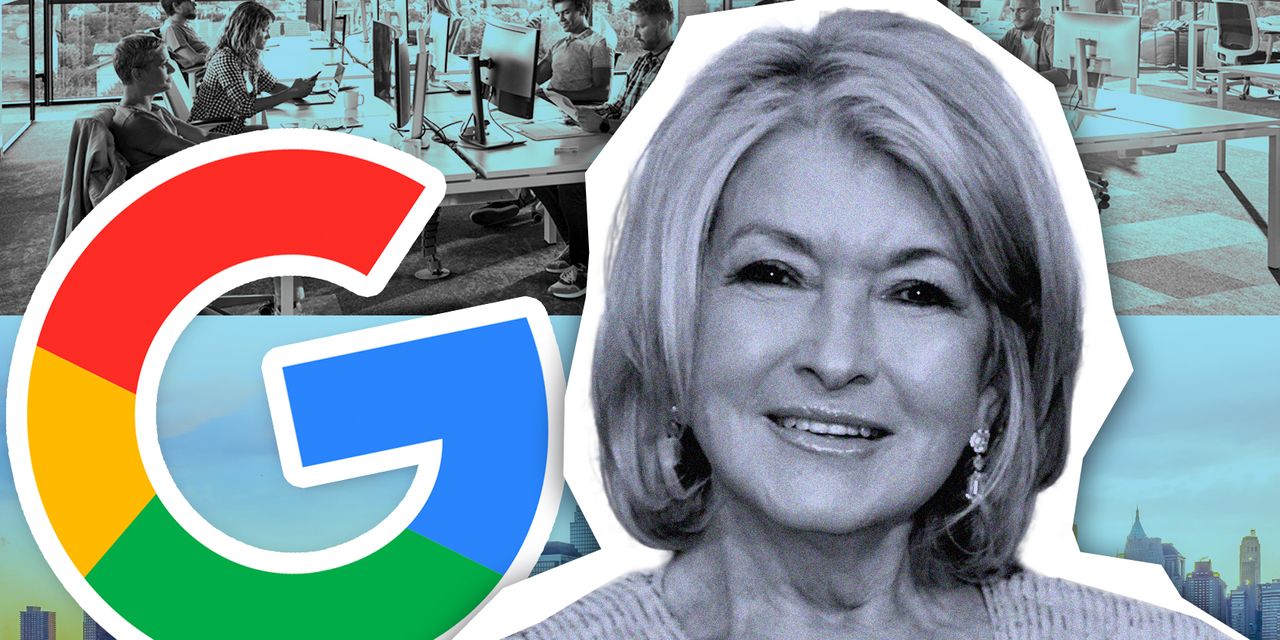

Is it possible times were simpler before and during COVID-19, a virus that turned the world upside down, and sent office workers home? Alphabet Inc.’s

GOOGL,

GOOG,

Google, Amazon.com Inc.

AMZN,

Martha Stewart, Farmers Insurance and some Wall Street banks have effectively told remote workers they’re getting too comfortable.

There’s now a rallying cry by companies to get back to those water-cooler moments, intra-silo chit-chats and face-to-face meetings during which ideas are born. That’s the theory anyway. There’s just one problem. It ain’t going so well, if recent attempts by major U.S. companies are anything to go by.

Nicholas Bloom, an economics professor at Stanford University and prominent remote-work researcher, said employers have a dilemma on their hands: How do they win over employees? He agrees that company-employee relationships are a two-way street. “Firms with bad culture should try to fix it first,” he said.

Hybrid work needs everyone on board, he said. “Indeed, culture is generally better when folks come to work on a few high-energy days and on the same days,” Bloom told MarketWatch. “Coming into a half-filled office is not great, and if anything, it is more likely to lead to cliques in some quiet side room.”

Google is cracking down, Martha Stewart is speaking up

Google is the latest to crack down on remote workers, recently calling on hybrid-work employees who are required to go into the office three days a week to do just that, and keep up their end of the bargain. Chief People Officer Fiona Cicconi outlined her stance in a company memo.

“If you’re on a hybrid schedule, you should be coming into the office regularly — 3 days per week for most Googlers,” according to Wednesday’s memo, which was reviewed by MarketWatch. The company said it will track I.D. badges, and consider action against very absent employees if they are chronically shaking off the office.

Last month, hundreds of workers at Amazon staged a lunchtime walkout in protest of the company’s policies, including a three-day in-office work requirement. A company spokesman told MarketWatch it would take time for people to readjust to a greater office presence but that more collaboration happens in person.

Others are taking a gentler approach: From June 12 to June 23, Salesforce

CRM,

will donate $10 for every day that staff members go to the office, Fortune reported this week, and it hopes to raise between $1 million and $2.5 million for charity in the process. Some described it as “a cute gimmick.”

Martha Stewart, meanwhile, recently said remote workers would cause America to “go down the drain” and likened not going back to the office as “not going back to work.” Those working from home are presumably padding around in their slippers. (Coincidentally or not, she gave that interview to Footwear News, a trade publication.)

“Is it possible times were simpler before and during COVID-19, a virus that turned the world upside down, and sent office workers home?”

Some might say it’s a bit rich for a multimillionaire who does not have to commute to work five days a week, and sit at a desk for eight hours a day, to tell others to do just that, while others may contend that Stewart is where she is today because she showed up to the office in person.

Bloom sees her point. But he also suggested the push-and-pull to get employees back to the office is a three-way street, if not a spaghetti junction. Employees who turn up in person and sit under those harsh lights for eight hours could be doing a lot of the heavy lifting for the remote workers, he said.

He believes hybrid work represents companies and employees taking the high road. “You pay top-market rates for top-talent, and to keep them productive you have them hybrid in the office typically Tuesday to Thursday for mentoring, innovation, building culture etc.,” Bloom said.

And the low road? “Closing all offices and letting employees work anywhere, including possibly abroad,” Bloom said. In this scenario, he added, it’s an unequal relationship. “Under this you save, maybe, 20% of costs by having no space, possibly another 20% to 50% on labor costs, but take a big hit on productivity.”

West said, just like with a family, employees representing all levels of seniority and different teams need to work together. “Offices full of people who are all at one level of the hierarchy don’t have the vibe people need,” she said. “You need to be able to network up and over, and with people outside of your team, across different parts of the organization.”

Health relationships need consistency — not unpredictability

Sudden U-turns in agreements are not popular at home or at the office. Farmers Insurance Group told employees that they could work remotely. Some staff members bought houses, but that soft approach changed when Raul Vargas took over as CEO of Farmers Group, and effectively called them back by September.

In a piece outlining a “revolt” by employees, The Wall Street Journal quoted one worker’s response: “I sold my house and moved closer to my grandkids. So sad that I made a huge financial decision based on a lie.” The company said the move will impact approximately 60% of Farmers’s workforce.

What was once a delicate dance between manager and employee has turned into a slew of ultimatums. What are their employees returning to, and what are they resisting? They may miss certain things about office life — brainstorming at lunch and friendly banter. But perhaps there are other things they don’t miss.

Employees have a lot to lose too, West said. “But without careful attention to these costs, and a plan to fix them, no one will want to come back. And simply saying, ‘but creativity happens at work,’ isn’t enough. How, in this company, does face-time promote creativity? What are people losing by not coming back?”

Management needs to tell remote employees they will miss out. “No one will feel FOMO if an in-person event was sad, poorly attended and in a dimly lit room that could double as an FBI interrogation room,” West added. “The office needs to be bright, vibrant, and have a mix of quiet spaces and happening ones.”

“What began as a delicate dance has turned into an ultimatum. What are their employees returning to, and what are they resisting?”

Do offices need to scrap oppressive fluorescent lighting and be more welcoming? Silicon Valley firms may have a head start on creating a warm environment. Google’s offices are famous for mimicking home, with lounge areas, massage chairs and green spaces. Rather than being white and sterile, they have multiple textures and colors.

But sweet treats, soft drinks and relaxation rooms with plants may not be enough at many office spaces, which are — frankly — less inviting than many people’s homes, especially if they are commuting for nearly 30 minutes one way (the average commuting time, according to the U.S. Census Bureau). Plus, some notable tech companies have been cutting back on perks in a bid to reduce costs, in another sign that the connection between workers and employers has long exited the honeymoon stage.

The comparison between the workplace and domestic relationships may not be so far fetched. Some 69% of workers said their managers impacted their mental health, matching the portion of workers who said their spouses or partners impacted their mental health, according to a study released in January by the Workforce Institute at UKG, which researches workplace issues.

What’s more, offices with a toxic culture may just get worse with some employees working from home and others showing up. In fact, almost half of workers still feel pressured to engage in office politics, a recent study, “Backstabbing, Credit Snatching and Blame Gaming,” from researchers at Pepperdine University found.

The bottom line: Office culture, like “setting up house,” incorporates the physical and cultural environment. West said no relationship works if you don’t spend time together. “There needs to be networking time and work time, formal and informal contact, and chances to make your invisible work turn visible,” she said.

Emily Bary contributed.

Read the full article here