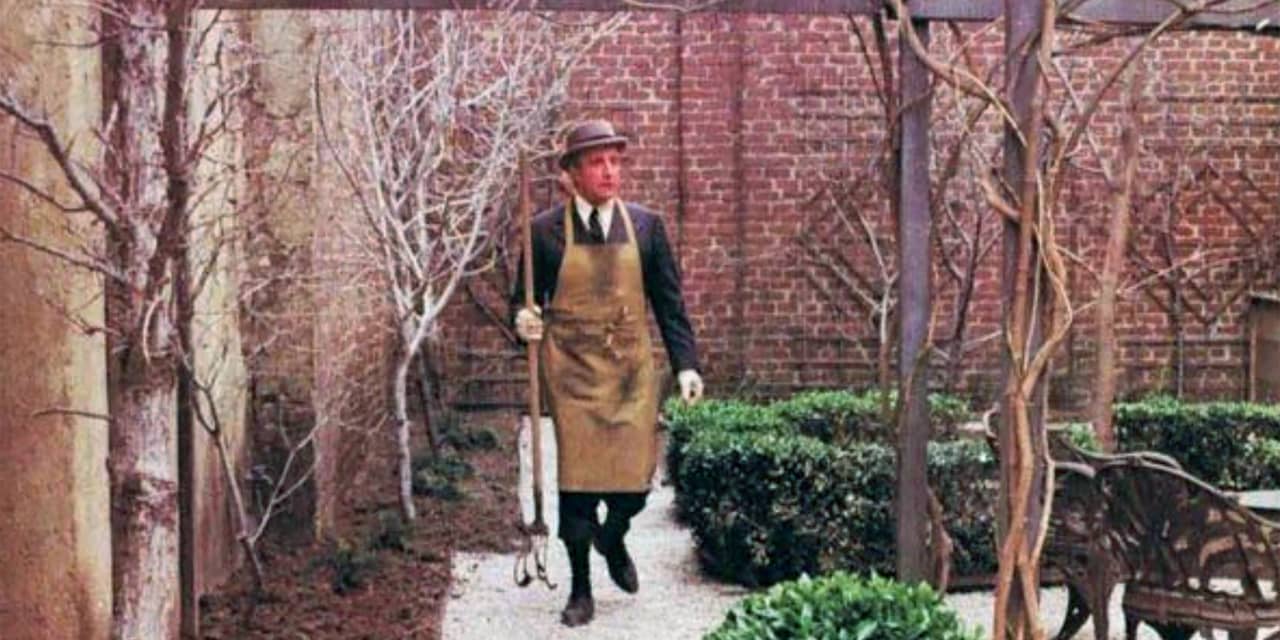

There will be cuts in the spring, to paraphrase Chauncey Gardner in the classic satire film Being There. He was, in truth, Chance, the gardener, a dimwitted savant played brilliantly by Peter Sellers. His simple utterances about growth in the spring and other matters horticultural were taken by Washington’s elite, including the president, to be profound statements about the economy.

This was called to mind by the growing certainty that the Federal Reserve will cut its key rate at its policy meeting concluding on March 20, just after the start of spring. That’s even though economic conditions don’t appear to call for monetary easing, with inflation still above the central bank’s 2% target and labor market conditions suggesting full employment.

Indeed, the Fed has lowered interest rates only five times in the past 90 years in stretches when the so-called core consumer price index (excluding food and energy costs) was growing faster than the unemployment rate, according to a research note from Bank of America’s investment strategy team, led by Michael Hartnett. With core CPI up 3.9% in the past 12 months, more than the 3.7% jobless rate in December, a rate cut now would rank among those rare instances.

More to the point, four of those cuts happened in 1969, 1974, 1980, and 1981, right around the 1979 release of Being There. And for those who weren’t there then, this was the time of stagflation, that condition of rapidly rising prices and sluggish economic growth. Much of that could be blamed on the Fed, which failed to fight inflation long and hard enough. (For the record, the other example was in 1942, during World War II.)

The BofA note cites this history in the context of what it terms the market’s “zeitgeist,” the widespread belief that the Fed will succumb under the first sign of pressure to cut. That’s why Wall Street is so “risk on,” or bullish. That is, until the market deems easing of monetary policy to be a “policy mistake,” which could be evidenced by a sharp slide in the greenback. Alternatively, Wall Street could get spooked by a decline in nonfarm payrolls in a worsening jobs market consistent with recession.

Nomura Securities analyst Yujiro Goto looked at six other Fed rate cut cycles of more recent vintage and divided them into two types: “pre-emptive” in 1995, 1998, and 2019, when no recession followed, and “full scale” cuts, during recessions in 2001, 2007, and 2020.

Bond and stock markets showed differing patterns around the times of the two types of Fed easing programs. Bonds would rally initially in either instance, with five-year Treasury yields falling in the 125 trading days before the first Fed cut, Goto found. But in the 125 trading days after the pre-emptive cuts, five-year yields basically moved sideways, while they continued to slide after the Fed commenced a full-scale rate program.

For equities, he found the

S&P 500

index typically struggled ahead of pre-emptive rate cuts, but then rallied after the Fed easing. Ahead of the full-scale rate cuts, stocks generally moved sideways and then didn’t recover once the Fed cut rates as a result of the recession.

Looking to 2024, much will depend on whether rate cuts follow the market’s expectations or hew to the Fed’s projections. The latter imply three reductions of one-quarter percentage point each by year end.

The federal-funds futures market sees an initial cut of a quarter point in March, from the current target range of 5.25% to 5.5%, with a 74.2% probability as of Friday, according to the CME FedWatch site. The futures market is pricing in at least six cuts totaling 1.5 percentage points by December.

Based on the rate-cut scenarios it examined, Nomura looks for bond yields to decline and U.S. share prices to trend sideways ahead of the pre-emptive cuts the bank sees starting in June. If total cuts are limited to three-quarters of a percentage point (consistent with Fed projections), Goto thinks yields then will move sideways and stocks will stage a clear rebound. “However, if full-scale rate cuts seem likely, we think U.S. interest rates will continue to decline and share price performance will weaken,” he adds.

Bulls think rate cuts will lure all the cash on the sidelines earning 5% in money-market funds into stocks. Much of that fled bank deposits paying basically nothing and are held by risk-averse savers, especially seniors.

If funds futures are right about much sharper rate cuts than the Fed itself projects, Nomura’s reading of history implies an unfavorable outlook for equities. To be sure, the limited pre-emptive rate cuts that the Fed projects would be bullish for stocks, but then the interest-rate markets would be wrong.

A conundrum, indeed. What would Chauncey say?

Write to Randall W. Forsyth at [email protected]

Read the full article here