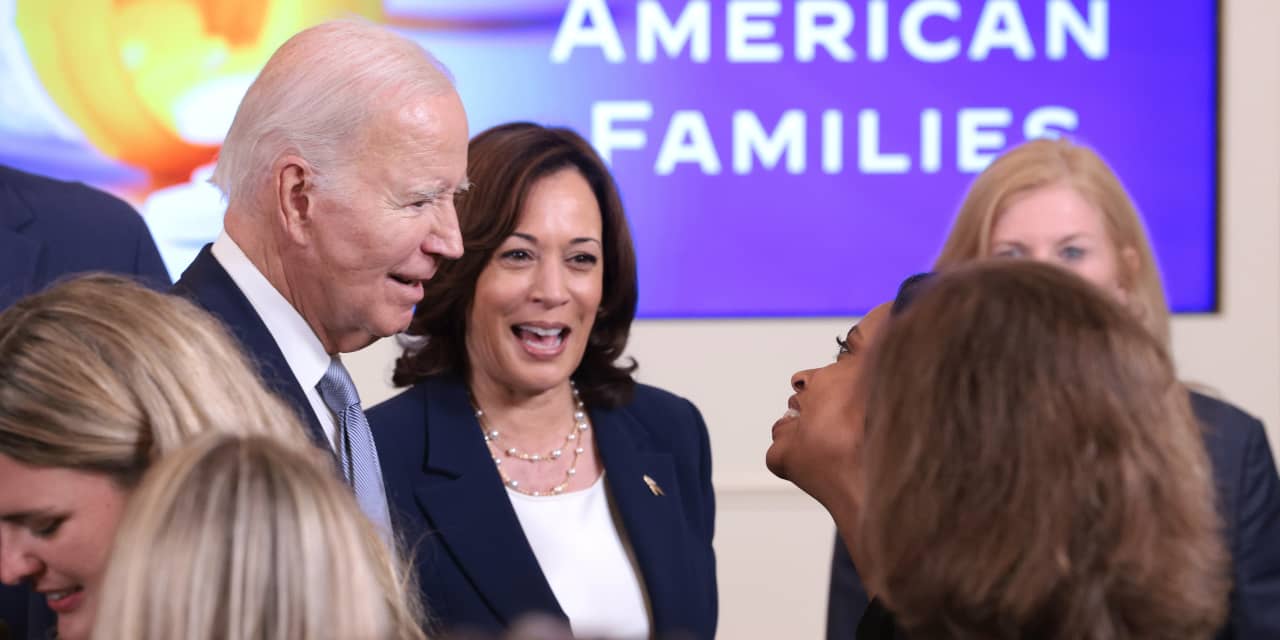

By Feb. 1, the federal government will send an initial offer for each of the 10 drugs selected for the first round of negotiations under the program, which was established under the Inflation Reduction Act and touted by President Joe Biden as part of a broader effort to drive down healthcare costs. Yet several lawsuits challenging the program could also reach turning points in the coming months, raising the prospect that some elements of the program could be stalled before they get off the ground.

Nine lawsuits filed by drugmakers and industry groups are currently challenging the constitutionality of the negotiation program, and even more are likely on the horizon, legal experts say. In at least one case, filed by AstraZeneca PLC

AZN,

the court has indicated that it could make a decision by March 1–the day before the drug companies’ deadline to either accept the government’s initial price offer or make a counteroffer.

While some drug companies are seeking court rulings that would exempt them from the program, the cases could also have a much broader impact. In its lawsuit against the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, for example, the business lobbying group U.S. Chamber of Commerce has argued that the court should block the government from implementing the negotiation program.

So far, courts have only grappled with the merits of the industry’s legal arguments in one ruling — and it didn’t turn out well for the industry, said Zachary Baron, director of the Health Policy and the Law Initiative at Georgetown Law’s O’Neill Institute. The Ohio federal court judge hearing the Chamber of Commerce’s case rejected the Chamber’s effort to halt the program by Oct. 1, 2023 — the deadline for selected drugmakers to sign agreements to participate in the negotiation process.

Participation in Medicare, “no matter how vital it may be to a business model, is a completely voluntary choice,” U.S. District Judge Michael Newman wrote in the late September ruling. As there is no constitutional right or requirement to do business with the government, Newman wrote, “the consequences of that participation cannot be considered a constitutional violation.”

A decision on the full set of claims in that case could come in the next several months, Baron said. No matter how courts rule in this and similar cases, legal experts say, the decisions are certain to be appealed.

The negotiations and surrounding legal battles will play out in an election year when costs and affordability are among voters’ top healthcare concerns, pollsters say. “Voters are extremely frustrated and exasperated by healthcare costs in this country,” Jarrett Lewis, partner at political and public affairs research firm Public Opinion Strategies, said during a Wednesday healthcare policy panel discussion hosted by Bipartisan Policy Center. But they’re also focused on the short-term, with little interest in policy shifts that may take effect in 2026 and beyond, Robert Blendon, professor emeritus at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said during the panel discussion. The first Medicare-negotiated drug prices are set to take effect in 2026.

The negotiation program brings drug companies into line with other healthcare industry players who do business with Medicare, advocates say. “What the Inflation Reduction Act does is the same thing the government has always been able to do with other healthcare providers”–specifically, negotiating the rate that Medicare pays, Kelly Bagby, vice president of litigation with AARP Foundation, said at a press briefing Wednesday. “This is not novel.”

Outside the courtrooms, pharmaceutical executives say IRA provisions are already affecting their decision-making. A top concern, they say, is that the law subjects small-molecule drugs to negotiated prices once they’ve been available for nine years, while more complex biologics have 13 years. “When my team is working on corporate development transactions, whether it’s a licensing or an M&A deal, small molecule opportunities are inherently worth less now,” Gilead Sciences Inc.

GILD,

chief financial officer Andrew Dickinson told MarketWatch.

That’s a concern, Dickinson said, because most new product approvals in the industry now spring from external innovation outside big pharma, and the major drug companies are relying on accessing that innovation to fuel their future growth. Yet the law “provides a huge disincentive” for smaller companies to develop small-molecule drugs, Dickinson said, and far fewer of those early-stage companies will pursue that path “unless they really have incredibly transformative data.”

Merck & Co. Inc.

MRK,

CEO Robert Davis also warned of the law’s drug-development impact in comments to reporters on the sidelines of last week’s J.P. Morgan Healthcare conference in San Francisco. “Much of innovation happens after the initial launch,” Davis said, noting drugs’ limited time on the market before they become subject to potential negotiation. He pointed to Merck’s blockbuster cancer drug Keytruda, which was launched in 2014. Today, “we’re just probably a little over halfway through the total clinical programs for Keytruda,” Davis said.

What’s more, it can take seven to nine years to get clinical data, particularly overall survival rates, for earlier lines of therapy, Davis said. “If you only have nine years for a small molecule, who’s going to pursue that?” he said. “So I worry about the unintended consequences to drug development.”

Merck last June became the first drugmaker to sue the federal government over the negotiation program. Its diabetes drug Januvia was among the first 10 drugs selected for negotiation.

While the court cases play out in the public eye, the actual drug-price haggling will happen largely behind the scenes. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the federal agency that administers Medicare, won’t publicly discuss ongoing negotiations, including the initial offer, unless a drugmaker decides to disclose details on the process, a CMS spokesperson said. CMS is set to publish maximum fair prices for the selected drugs on September 1 and a public explanation of those prices by March of next year.

Depending on the status of the first wave of lawsuits, even more litigation could pile up next year when the next batch of drugs is selected for negotiation, Baron said. Given the time and resources the industry has already devoted to thwarting implementation of the program, he said, “I don’t expect them to just take the ball and go home.”

Read the full article here