A previous version of this article was published to members of High Yield Landlord on April 17.

Clipper Realty (NYSE:CLPR) is a REIT formed in 2017 by combining properties held by its principals, mainly members of the Bistricer family. They are all long-time real-estate investors in New York City.

Here are a few summary points on who and what Clipper is:

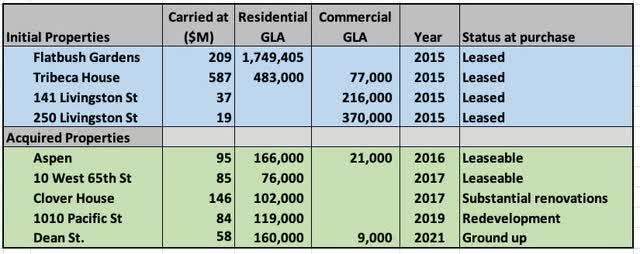

- Owner of 9 properties in Manhattan and Brooklyn (see Appendix)

- Two are purely commercial and 4 are purely residential

- Two properties are in development or lease-up

- The earliest debt maturity on mortgages for the other 7 is in 2027

- Average rents are above their 2019 values but not by much

- They focus on developing new residential properties

- Their cadence is about 1 every 2 years

- They have no credit revolver (much more on this below)

The founding principals own 62% of the common stock of Clipper and have never sold any of their own stock. (The ownership is via Class B LLC units, which reliably confuses various computers.) One point of forming a REIT was to raise capital. The IPO raised $130M and Clipper has issued no stock since.

The original holdings of Clipper include residential and commercial space. While the commercial space has fewer square feet, it contributes a substantial fraction (about a third) of total Net Operating Income, or NOI.

The focus of growth for Clipper is residential space. In particular they are a serial developer (including redevelopment) of multifamily buildings in NYC.

A second point of becoming a REIT was to protect the principals as they pursued such development activity. We will see how this works below and that the REIT transition offloaded risk from them onto shareholders. (I’ve made this point in prior articles too.)

I first wrote about Clipper two years ago. That article focused mainly on their real estate and on traditional REIT metrics.

This is typical of nearly all articles on Clipper. And all of those, including my first one, completely miss the point.

In contrast to the usual REIT article, here we will start with how and why Clipper is Strange and work our way to the more usual story of earnings from operations.

How Clipper is Strange

When it comes to sources of capital, normal REITs rely on a combination of issuing stock, investing retained earnings, capital recycling, raising debt by issuing Senior Notes, and perhaps refinancing mortgages. Clipper relies only on refinancing mortgages.

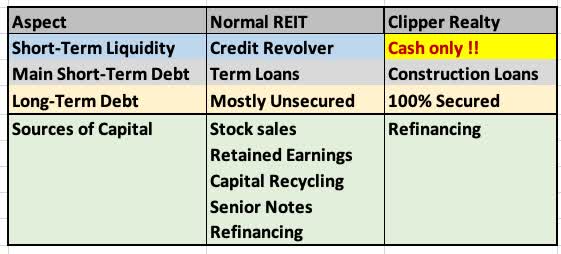

This table compares aspects of the capital stack and of capital raising for Clipper, to those of a more normal REIT.

RP Drake

The three rows below the title row relate to the capital stack. The single most unusual aspect of Clipper is that they have never had a Credit Revolver for short-term liquidity. They rely entirely on holding cash.

There is a positive reason for this. A Credit Revolver always contains covenants related to the entire business. If you violate them, the creditors can take over the company and you may end up with nothing or close to it. We have seen this play out with several REITs in recent years, for example CBL & Associates (CBL).

The downside is that you might run out of cash. At that point, if you still want to avoid general debt, your main option is to dilute shareholders. As we will see below, that is a real possibility over the next few years at least.

Having a Credit Revolver often comes along with (or requires) Term Loans, which Clipper also avoids. They do, however, have some short-term debt in the form of construction loans or short-term mortgages on development properties. These too are secured only by the properties they finance.

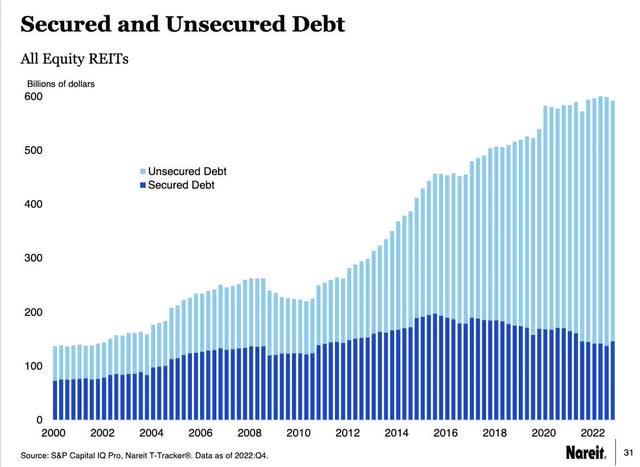

As to Long-Term Debt, the REIT industry has moved over time to primary use of unsecured debt. You can see this in the next graphic, from the NAREIT T-Tracker.

NAREIT

The Credit Rating agencies much prefer unsecured debt. So if you want an investment-grade rating you need to play along.

Clipper does not play along, relying instead 100% on secured mortgage debt. They have a mortgage on each property and emphasize that these are not cross-collateralized. Each encumbers only a specific building.

Clipper is not the only REIT to take a mortgage-based approach. Notable others include Urstadt Biddle (UBA) and Macerich (MAC). [Though Macerich got themselves in trouble in 2020 because they also maintained a substantial balance on their Credit Revolver.]

But even among this group of REITs Clipper is an outlier. Urstadt Biddle carries long-term debt at well below half their gross property value. Macerich runs around half.

As best I can tell, Clipper runs at something near 75% and wants to stay that way as properties appreciate. Of the 7 properties Clipper owned before 2018, they have refinanced 6.

The Risk from the Clipper Mortgages

There is nothing inherently wrong with the approach of Clipper. Some advantages were clear above.

If you have ever owned a house with a mortgage you know the math. If you have 25% down and the property appreciates 5%, you gain 20% on your invested equity. The downside is that prices do not always go up. I’ve met people who spent 10 years “under water” until they could sell some house and get their money back out.

In the commercial realm it is tougher. Mortgages often have a duration of only a few years with a balloon payment due at maturity.

The upshot is that in good times you can refinance and extract large gains. But in bad times you must inject more equity or lose the property. One risk with Clipper is that low property prices will create a need to inject more equity when mortgages mature.

In that scenario, sale of other properties helps little since they too would be down in value. If cash liquidity is low at such times, the job of the existing shareholders is to get diluted.

That dilution can get massive. Green Street says that apartment prices are down about 20%. That may or may not apply to NYC.

But suppose it did and suppose a mortgage on a $100M building financed at $75M was due now. The current property value would be $80M, the current equity would be $5M, and the needed equity to enable refinancing would be $15M.

How much that would dilute shareholders would depend on the Market Cap. Today if it were one building, the dilution at today’s Market Cap would be 7%.

But if seven buildings were in the same state, the dilution would approach 50%. And if the Market Cap dropped further, the dilution could become much, much larger.

Moderate dilution may not be the end of the world for long-term investors. They get back in the black rapidly with property appreciation.

My personal risk aversion has grown over the past couple of years, for reasons discussed in several articles. So today I would not sign up for a REIT using this model. But it was OK with me when I bought CLPR a couple years ago.

With the earliest such mortgage due in 2027, Clipper has plenty of headroom to wait for the right moment to next refinance those older properties. To my mind that aspect is not the largest risk. Instead, their challenges lie with financing their development cycles when such refinancing is difficult.

Let’s see how that has been going.

Cash and Cash Burn

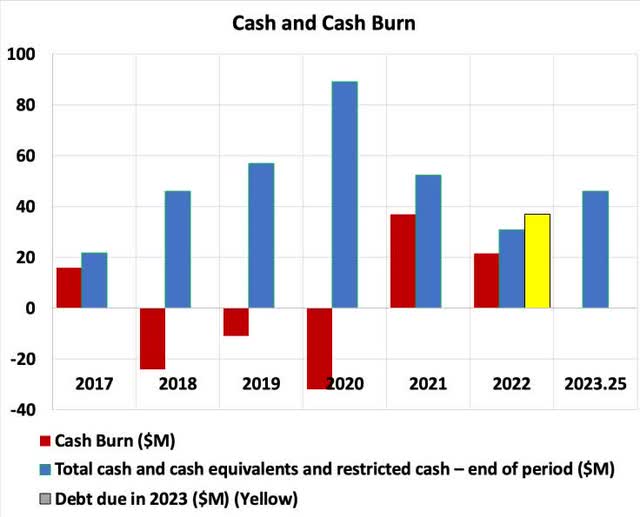

Here is the history of the cash balance of Clipper:

RP Drake

Two years ago, their $90M of cash seemed ample to provide liquidity for their needs. That cash could cover $10M of General & Administrative costs, $40M of interest expenses, and the $20M they had due in 2021 on their property at 1010 Pacific Avenue.

We will come back to how things changed from there later. The bottom line here is that Clipper burned cash in 2021 and 2022, ending 2022 with about $30M of cash, a third of what they held two years ago.

Meanwhile the annual expenses increased modestly and the debt due (in 2023) increased to $37M (yellow bar). So at the end of 2022 Clipper was technically insolvent. They did not have the liquidity to cover their debt maturing in 2023.

They fixed this by raising about $20M in early 2023, through a refinancing their newly completed Pacific St property.

Being on the edge of insolvency is not good. Let’s look at how it came about, then where Clipper can go from here.

Funds Raised and Spent

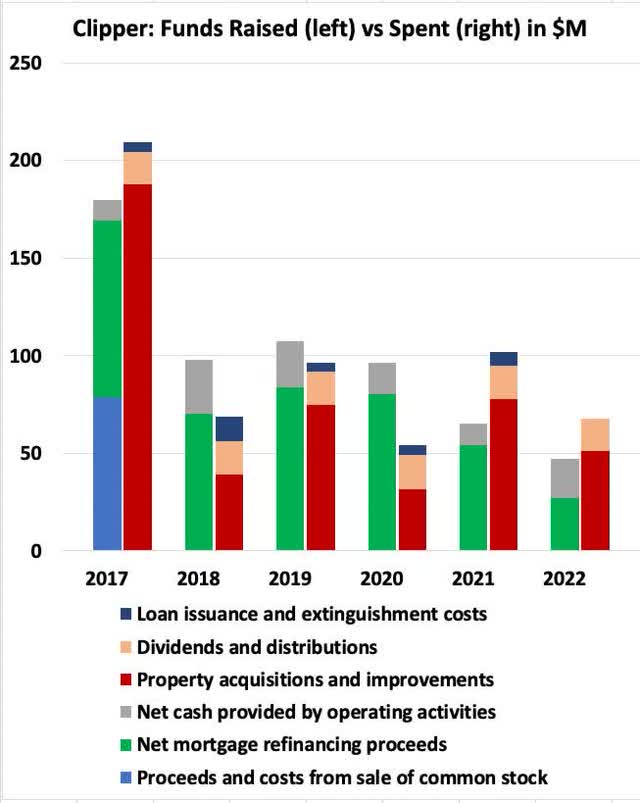

Here is the picture of fund raising and spending by Clipper, since the IPO.

RP Drake

The main colors you see are green (mortgage refinancing proceeds) and red (capex for acquisitions and development). There are two strange aspects to this plot, compared to other REITs.

First, the Cash from Operations (grey) is small compared to the funds from refinancing. Second, the dividends (beige) are small compared to the capex.

This is NOT normal but is a consequence of the business model and high leverage. Almost every article you see on Clipper, including my first one from two years ago, and in addition most of what they talk about on earnings calls, focuses on the typical REIT stuff in the grey and beige bars. All such discussions miss the point.

In the graphic, we see the Clipper business model in action. The funds raised exceeded the funds spent from 2018 through 2020, but after that the model ceased working well. This ran down their cash to its current, dangerously low level.

Surviving 2023

We saw above that about $100M of cash is needed to have a reasonable amount of liquidity. But the kicker is that this is needed at lowest-cash moment of their development cycle, when maximum capital is tied up in a construction project that has yet to be refinanced.

In addition, we can see that the Cash from Operations is not reliably bigger than the dividends. In other words, there is no money from operations to help with the shortfall (more later on that). So it is all about mortgages, as always with Clipper.

For 2023, it is likely that only two of Clipper’s 9 properties are in play. Six of the 7 others have been refinanced at least once since the IPO. And the current credit and property markets leave them unlikely to be able to refinance and take cash out on favorable terms.

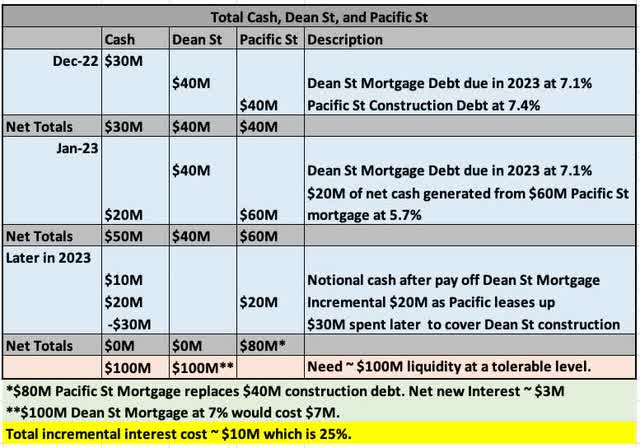

The two properties in play are Pacific St, just finished with construction, and Dean St., just starting construction. So we take this look at cash and at the debt on those two properties, with a likely future displayed in this table.

RP Drake

We see in the top section of the table where things stood at the end of 2022. All numbers are rounded to the nearest $10M. There was $30M in cash, $40M in mortgage debt on Dean St and $40M in construction debt on Pacific St.

The second section shows what happened in January 2023. They raised $60M from Pacific St., paid off the construction loan, and netted $20M in cash. This left Clipper with $50M in cash, $40M in mortgage debt on Dean St and $60M in mortgage debt on Pacific St.

The third section shows some of what will transpire later in 2023. Paying off the Dean St. mortgage will leave them with $10M in cash. Increased leasing of Pacific St. will free up an additional $20M on that mortgage, adding to cash. And construction on Dean St., in addition to the $70M they already have in it, will require the $30M of cash they have accumulated (my estimate).

This will leave Clipper, notionally, with no cash, no debt on Dean St, and the $80M mortgage at 5.7% interest on Pacific St. It seems clear that they will seek to re-establish their liquidity via a post-construction mortgage on Dean St. If not this year, this might be in 2024.

The incremental debt on Pacific St. is costing about $3M per year. If a $100M mortgage is placed on Dean St., at a 7% interest rate, the total incremental interest expenses would be $10M.

On the one hand, regarding capital, this could put Clipper back where they were 3 years ago, with $100M of liquidity and small debt at most. From their past patterns, it would not be a surprise to see a next acquisition as Dean St. nears completion.

What I failed to focus on in early 2022 was the cash burn and later cash from refinancing new buildings, across their construction cycle. This was hidden until recently by the steady influx of funds from refinancing older buildings.

Without such refinancing, their liquidity dropped to about zero at the low point through their construction cycle. This has left these guys dancing on a zero-liquidity tightrope without a fricking net.

If the markets had been evolving so that Clipper could take more cash out of their other properties, the present insolvency threat would likely have been avoided. But working off new properties only, we would see their liquidity go from near $100M to zero across their development cycle. This is too close to the edge for me; you have to decide whether it is for you. I sold as soon as the story became clear to me.

From a capital resources point of view, one sensible course of action now would be to dilute shareholders by $100M (~30%), which would put the capital stack on a sounder basis. This is one way that it plays out that the shareholders are the security for the principals of Clipper.

Another alternative would be to enter a Joint Venture and sell part of one or more properties. But at present market prices, there may not be much value there at the moment.

Beyond all that, though, things get worse….

Operations in 2024 Do Not Help

It is natural to think that the leasing up of Pacific St. and Dean St. would make a positive difference. But with the likely increase of interest expenses (about $10M), there will be little if any impact.

My estimate is that those two properties will increase total revenues by 13%. This is based on their gross leasable area and assuming their rents per square foot are like those of the higher rent Clipper properties.

This is what you get for 2024 operations, by comparison with 2022:

RP Drake

The first row shows total revenue (shaded blue). The next four (shaded orange) show expenses. The sixth row (shaded blue) shows an estimate of Adjusted Funds From Operations, or AFFO.

Lower rows show shares, AFFO/sh, Dividend/sh, and the AFFO Payout ratio. That ratio typically has been over 100% for Clipper. These examples are in the normal range.

The implication is that Clipper has drawn and will draw on their liquidity to top off their dividend. So the dividend seems unlikely to be cut, unless perhaps after a significant dilution. But the operations overall do not help their liquidity position.

Net Asset Growth Has Slowed

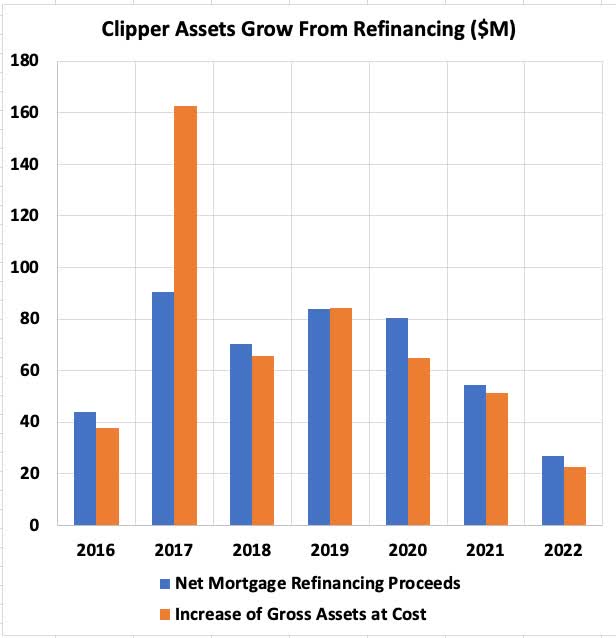

My second article on Clipper, a year ago, focused on understanding and documenting the business model described above. That article showed how it is refinancing that drives the increase in Gross Assets at Cost. Updating the plot:

RP Drake

Once sees that the connection between these two elements continues. But the annual magnitude has dropped.

For 2023, the net mortgage financing proceeds include raising a net of $40M on Pacific St. and paying down the same amount on Dean St. So net proceeds, if any, will come from further loans on Dean St.

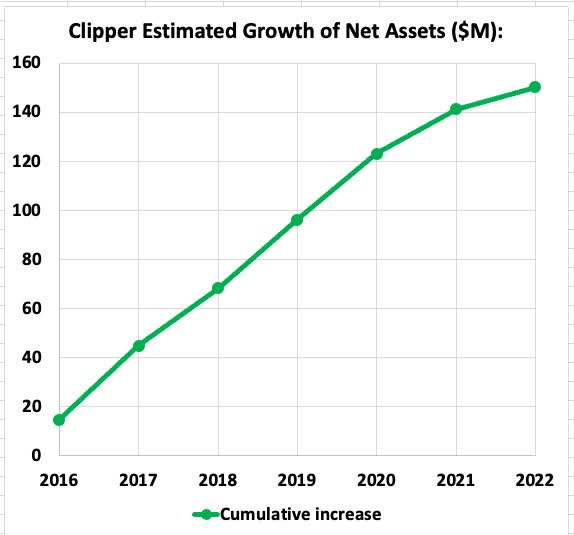

In addition, that second article evaluated the impact of leveraged refinancing. It concluded that the growth of Net Assets that enabled the new borrowing was in the ballpark of 1/3 of the funds raised.

We can think further about [the growth of assets] based on loan to value. This is necessarily an approximate calculation but still worth doing.

Consider that loan to value for commercial mortgages like theirs is somewhere near 75%. In each year, Clipper can borrow 3/4 of the increase in actual Net Gross Assets.

Turning this around, the increase in actual Net Gross Assets is 4/3 of the new borrowing. After leveraging this increase at 75%, the retained increase in actual net gross assets is 1/3 of the new borrowing.

Here is the updated version of the resulting plot:

RP Drake

The discussion in that article would put the Net Assets near $240M in 2016, so they grew at about a 10% rate from then through 2021. However that growth slowed to less than 5% in 2022.

From the discussion above, growth this year will include perhaps $12M from the Pacific St completion. Dean St. will also contribute assuming there is refinancing after construction.

The Bottom Line

The Clipper business model features using funds from new and refinanced mortgages to provide the cash to fuel new development. By comparison, cash earnings and distributions are small potatoes. Clipper also by intent operates without the usual safety net of a credit revolver, relying on their cash balance for all their liquidity.

For this model to work, the refinancings must sustain the cash balance at a level adequate to cover potential costs of debt and operations if events move against them. The model has broken since 2020.

When (not if) some unexpected expense of some tens of $M comes up, Clipper may not have the money to cover it. In this context it is worth noting that the leases on their office properties expire in a few years. If these are not renewed, retenanting is likely to cost a lot of cash that Clipper does not now have. This is another source of possible dilution.

In retrospect, to protect shareholders, Clipper should have raised another $100M in cash to start with. This would have meant that they had sufficient capital at the low point of their development cycles to protect against adverse events at least to some degree. It would have also freed them from needing their older properties to always appreciate so they could keep refinancing them.

But perhaps the principals don’t care; they can be sanguine about all this. They did an IPO, pushed the value of the real estate owned by Clipper up more than 50% over six years, and then may have to take a 30% dilution.

But they are still operating above water, barely, and can tap shareholders if a bit more cash is needed. The cash flows of their properties are increasing and this will end up reflected in property values in the long run.

The capital markets will return to sensibility and they will be able to extract their share.

One remaining angle is Flatbush Gardens. The failure of NYC to allow redevelopment there is an enormous disappointment. Clipper announced within the last year that they are now seeking to sell the property. But more recently they said on the recent Q1 2023 earnings call that they have taken Flatbush off the market.

It would not be unreasonable for a long-term investor to hold CLPR today. The risks involve whether the capital and real estate markets will enable them to execute their strategy without massive dilution of shareholders, and also how long it will take to recover that value if they do dilute.

Part of that is normal real estate risk, with regard to demand for their properties and their success in executing their model. My view is that there is no likely problem here.

But part of the risk is also a macro-economic bet that the capital markets will mostly cooperate throughout the next decade. Time will tell about that.

As my own understanding of Clipper has evolved, so have my investment theses.

- My 2021 thesis: The NYC insiders who run Clipper will keep finding ways to grow NOI by 10% per year, and they likely will get approval to renovate Flatbush.

- My 2022 thesis: Clipper will sustain their cycles of new development funded by refinancing and will grow steadily.

- My 2023 unthesis: The Clipper development cycles bottom with too little cash for this cowboy.

My personal disappointment lies in not having seen this coming. On the one hand, clearer thinking about coming cash needs a year ago might have revealed what was likely.

On the other hand, a year ago M2 growth had already slowed (it has since reversed) so it was clear that inflation would come down. To me, it seemed unlikely that the Fed would persist in trying to kill the economy even after inflation was easing. But they are.

Continued turmoil in the credit markets and high interest rates are headwinds for the Clipper business model. Shareholders may ultimately pay for that.

Appendix: The Clipper Properties and Price History

Here are the Clipper properties:

RP Drake

There is a lot of history on Flatbush Gardens, which the Bistricers bought at the behest of NYC. There were apparently promises to let the redevelop it and expand the GLA, but nearly 20 years later nothing has happened.

Here is the price history of CLPR since the IPO:

YCHARTS

It seems to me that the pre-pandemic high prices likely assumed that Flatbush would be redeveloped. With hope seemingly gone for that, we may never see such prices again.

In contrast, the Net Asset Value estimated above corresponds to $9 per share, so perhaps a return to the post-pandemic high would be reasonable with a recovery of the property and credit markets.

Read the full article here