Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

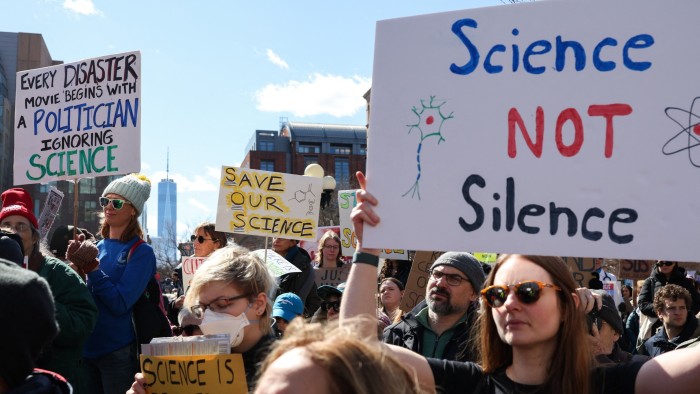

Science institutions in Europe and beyond are racing to hire researchers from the US looking to flee the Donald Trump administration’s crackdown on research agencies.

Cambridge university is among a clutch of top research institutions seeking to entice experts in fields from biomedicine to artificial intelligence as Washington pushes for big funding cuts and suppresses some areas of inquiry.

Researchers and top institutional officials in several European countries said they had been approached by US counterparts at varying levels of seniority about possible moves.

Deborah Prentice, vice-chancellor of Cambridge university, said it had “certainly begun organising”, pointing to possible funding injections for groups that “have somebody from the US who they’d very much like to recruit”.

Nations including China and France were also “gleefully” trying to attract US-based researchers to work in their universities, laboratories and industries, said Joanne Padrón Carney, chief government relations officer at the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

“There are other countries that are recognising this is an opportunity they could use in their favour,” she said.

The Trump administration has already sought to slash billions in funding from agencies such as the National Institutes of Health, although a federal judge issued an injunction this month against the biggest tranche of cuts.

The political climate in the US is “discouraging for independent investigator-driven research” and causing anxiety for European colleagues who may be able to offer a haven, said Maria Leptin, president of the EU’s European Research Council.

“What we can do is to make clear to our US-based colleagues that the European research community and its funders offer a welcome in Europe to those, regardless of nationality, who find their options for independent scientific work threatened,” Leptin said.

Sten Linnarsson, a dean at Sweden’s Karolinska institute for biomedical research, said the organisation was likely to start announcing vacancies earlier and was looking at ways to help US researchers seeking a bolt-hole.

“Our colleagues are telling us that they have colleagues in the US who are looking for somewhere,” he said. “Just to give them a place to land and find their way, we can give them six or 12 months sabbatical here — that’s very easy.”

The turmoil has led researchers in the US and overseas to ask whether the country is shifting away from its post second world war model of strong state support for wide-ranging scientific discovery as a motor for innovation and economic growth.

The chaos in US science has offered an opening to recruit researchers with connections to China, according to the Global Times, a Communist party tabloid newspaper.

“Under the pretext of ‘national security’, Washington has unsettled the field of scientific research,” read a commentary published last week.

“Facing mounting pressure, many [Chinese-American scientists] are reassessing their career trajectories and turning their attention to China, a country that is more open, inclusive and full of opportunities.”

US science faces a pincer movement from two aims of the Trump government: to cut state spending and to curb research relating to diversity, some vaccines and human causes of climate change.

Leading US scientists and administrators say that the endpoint of the process remains unclear, because of a lack of transparency, continual adjustments and legal challenges to some proposed changes.

But the uncertainty is in itself highly damaging, they add, because researchers including many younger scientists pursuing PhDs do not know if they will receive funding.

The potential transatlantic talent shift was “on the . . . radar” of leading UK scientific institutions, said Cambridge’s Prentice.

“Obviously it’s front of mind for me because many of my friends and former colleagues from the US are writing saying: ‘How do you get to Britain?’” said Prentice, a psychologist who was formerly Princeton University’s provost.

For Cambridge, she added: “It’s really about trying to make resources available for departments and units that have an opportunity to hire.”

France’s minister for higher education and research Philippe Baptiste has written to leading research institutions urging them to send proposals for priority areas to attract US-based science and technology talent.

“Many well-known researchers are already questioning their future in the US,” Baptiste wrote. “We would naturally wish to welcome a certain number of them.”

Southern France’s Aix-Marseille university has announced a programme for US-based scientists who may feel “threatened and hindered”, particularly by cuts in fields such as climate change.

Read the full article here