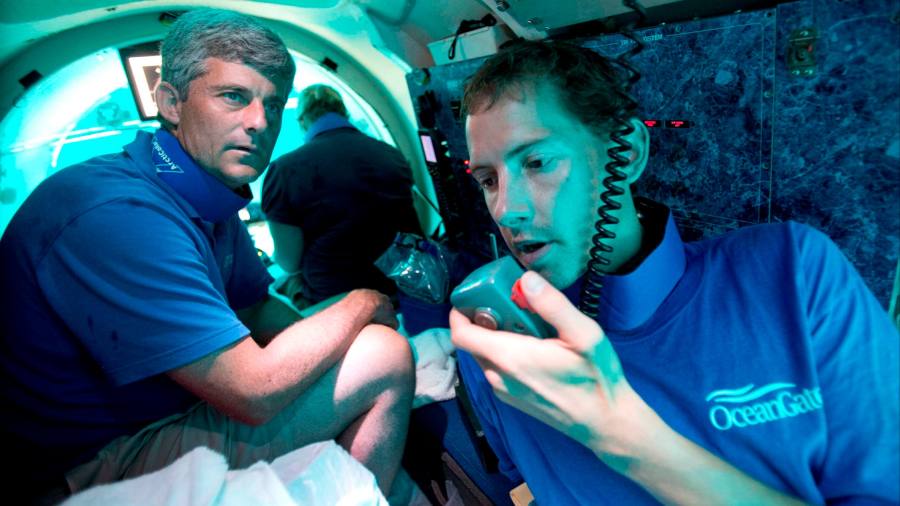

Stockton Rush launched the manned submersible operator OceanGate with vast ambition. “Stockton was opening up a new realm for humanity,” said businessman Fred Hagen, who twice visited the wreck of the Titanic with OceanGate.

Yet that vision proved difficult to fund, and ultimately appears to have cost Rush his life. The 61-year-old was one of five people on board OceanGate’s Titan submersible when it lost contact with its mother ship, the Polar Prince, during a dive on Sunday to the 3,800-metre depth where the Titanic’s wreckage lies.

Search and rescue teams discovered debris in the area on Thursday, which the US coast guard described as “consistent with a catastrophic implosion of the vessel” as it offered condolences to the victims’ families. OceanGate said it believed that those on board the craft had died.

OceanGate was founded in 2009, but Rush had set his sights on extreme travel decades earlier. In an interview with the Smithsonian magazine four years ago, the entrepreneur recounted how, as he was growing up in a wealthy family in San Francisco, he wanted to be an astronaut. His parents assured him he would grow out of that.

“I didn’t,” he told the interviewer.

Rush trained as a pilot, qualifying at just 19, and spent his college summers serving as a co-pilot on commercial flights, according to OceanGate’s website. He later became a flight test engineer on F-15 fighter jets; as long ago as 1989, he built his own experimental aircraft.

Later, entrepreneurs such as Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson began developing commercial space travel, but Rush turned his sights elsewhere. Shannon Stowell, chief executive of the Adventure Travel Trade Association, of which OceanGate is a member, said Rush had a “passion for the deep sea”, calling him “definitely a pioneer”.

Hagen said he could be “very stubborn, very adamant on how he was going to proceed”.

However, the project appears to have struggled with making economic sense of operating in the deep oceans. In an interview last year, David Pogue, a journalist for the US network CBS, asked Rush if he was making money on the operation.

“No,” Rush replied. “Not yet.” The OceanGate founder said others might describe $250,000 — the price per person of a trip to the wreck of the Titanic — as “a lot of money”. But he added: “We went through more than $1mn of gas.”

At the same time, Rush made no secret of his distaste for traditional safety measures, telling a CBS journalist last year that “at some point” safety was “pure waste”. In the earlier Smithsonian interview, he described the underwater submersible industry as “obscenely safe”.

“It also hasn’t innovated or grown — because they have all these regulations,” he said.

Hagen said Rush was “taking great risks, but doing them as carefully as possible”. He recalled of his own trips: “It was made extraordinarily clear that it was an experimental and unregulated vessel and that we were putting our lives at risk by participating.

“The word ‘death’ appeared three times on the first page — but like most people, you read it and you think: ‘Well, that’s not gonna happen to me’ . . . That’s the human response. To be honest, on my dive there were some tense moments where it flickered through my mind [that] we may not get up to the top again.”

The need to improve the economics of the operations appears to have been behind a key, and highly risky, design decision. The Smithsonian profile said Rush had chosen to make the Titan from carbon fibre because it would be far lighter, and easier and cheaper to transport, than a more traditional metal design.

The safety of the carbon fibre design appears to have been a flashpoint in the relationship between OceanGate and David Lochridge, the company’s former director of marine operations.

In a legal action filed in 2018 over his dismissal from the company, lawyers for Lochridge said he had expressed concern about the level of testing carried out on the carbon-fibre hull. Lochridge’s team said Rush insisted a real-time monitoring system in the hull would warn travellers if it began to crack, giving enough time for those inside to return safely to the surface.

However, Lochridge cautioned that the system might issue its warning only “milliseconds before an implosion”, the legal document said. He also warned that repeated use of the vessel could weaken it.

“Rather than address his concerns . . . they immediately fired Lochridge,” the legal action claimed.

OceanGate did not reply on Thursday to requests to comment on Lochridge’s action, which was brought after OceanGate sued him for allegedly leaking company secrets.

Rush’s push to develop commercial trips in a realm dominated by scientific expeditions worried others in the field. The manned submersible committee of the US’s Marine Technology Society wrote to Rush in March 2018 warning him of the potential risks of the company’s approach.

“Our apprehension is that the current . . . approach adopted by OceanGate could result in negative outcomes (from minor to catastrophic) that could have serious consequences for everyone in the industry,” wrote Will Kohnen, chair of the committee.

The committee was especially concerned that OceanGate had not submitted its design for certification by a classification society — organisations that provide a key link in the world maritime security system by documenting shipbuilders’ and operators’ adherence to construction standards.

Kohnen pointed out in an interview this week that there are only 10 vessels worldwide certified to carry humans as deep as 4,000 metres below sea level.

Tommaso Sgobba, an expert in safety systems who is executive director of the International Associations for the Advancement of Space Safety, said such independent scrutiny was vital because organisations tended to become biased towards their own way of thinking — and to be over-optimistic.

“No matter how good you are as an organisation, you need at some point an independent reviewer,” he said.

At the same time, Rush found an eager band of like-minded exploration enthusiasts, including through the Explorers Club, a New York-based group where he sat on the board of trustees.

Guillermo Söhnlein, who co-founded OceanGate with Rush but stood back from day-to-day operations in 2013, wrote on LinkedIn this week that “our annual science expeditions to the Titanic are his brainchild, and he is passionate about helping scientists collect data on the wreck and preserve its memory”.

Anthony Eddies-Davies, who runs Adventure Consultancy, which provides advice on safety in adventure tourism, said the Titan disaster would rebound on other ventures. “It will have a rattle on effect” for “anything to do with the deeper water side of things . . . it will definitely have a shock factor,” he said.

But even after the sub was lost, some supporters continued defending his approach — including Hagen. He compared Rush’s vision to that of the Wright Brothers, inventors of powered flight.

“Do you know how many people died trying to figure out how to safely get an aeroplane in the air and to create the aviation industry as we understand it today?” Hagen said. “That’s exactly what Stockton was doing was trying to democratise the depths and allow humankind to explore the last great frontier.”

Read the full article here