Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

India’s central bank governor has defended the country’s economic resilience, saying it was “well placed” to deal with spillovers from emerging global shocks as the spectre of protectionism and trade wars looms during Donald Trump’s second term as US president.

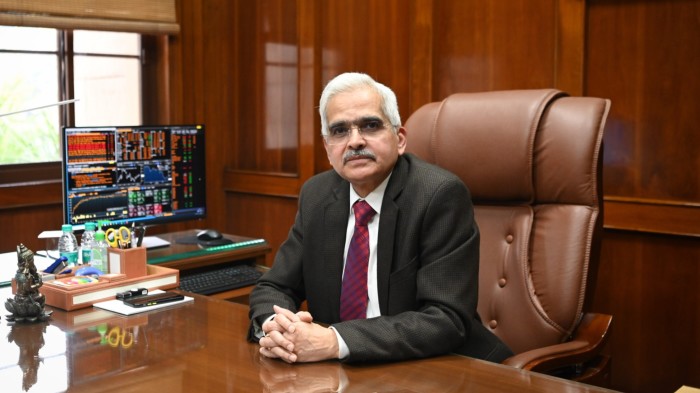

Reserve Bank of India governor Shaktikanta Das cited “protectionism and tariffs”, as well as “geo-economic fragmentation”, supply chain bottlenecks and surging commodity prices due to conflict as the biggest potential challenges for the world’s most populous country.

“These are issues on which we have no control,” Das told the Financial Times in an interview at the RBI’s headquarters in Mumbai.

But he said India was “well placed to deal with any kind of spillovers that may emanate from any external sources”, pointing to its “strong” $676bn of foreign exchange reserves and the fastest growth rate of any major economy.

“Whatever is happening within India, we can to a great extent influence, but what is happening outside, we have to defend against them,” he said.

While Das declined to comment on the incoming US administration, Prime Minister Narendra Modi enjoyed a good personal relationship with Trump during the latter’s first term in office, and New Delhi has forged a tighter strategic partnership with Washington. But Trump’s anticipated trade barriers could hit critical Indian export sectors, from drugs to IT services.

“It’s a different thing when you assume office,” Das said, when asked about Trump’s campaign pledge of blanket tariffs. “Every government the world over, when they impose tariffs they are fully mindful of what impact it will have on their domestic inflation.”

Das, whose second term expires before the year-end, is grappling at home with accelerating inflation, which breached the RBI’s upper target threshold of 6 per cent in October on the back of rising food prices.

Given those pressures, many economists expect the RBI’s monetary policy committee will hold its key interest rate at its meeting next month at 6.5 per cent, which would make it one of the few large central banks to not yet begin easing.

This month, India’s trade minister argued that the RBI should cut rates to prioritise growth.

Das said the RBI expected prices to begin moderating next month. He added that it was “very risky” to give forward guidance on rates “with so many uncertainties all around”, but noted that “headline inflation is our target and rightly so”.

India’s economy and equity markets are also showing signs of cooling. A set of weak quarterly corporate earnings, and a slowdown in urban consumption, has helped fuel a foreign investor equity sell-off that has pushed benchmark indices into correction territory from their September peak.

Goldman Sachs last week forecast that India’s economic growth would slow to 6.3 per cent in 2025 from an estimated 6.7 per cent this year. The bank’s analysts highlighted a 2 percentage point fall in bank credit growth in the third quarter to 14.4 per cent, after the RBI slammed the brakes on what Das called “exuberance” in unsecured lending.

The governor said India’s economy was “a mixed picture”, but added there was “no evidence” that RBI measures over the past year to rein in retail credit, which was ballooning at a rate exceeding 25 per cent earlier this year, were the cause of a weak urban consumption.

Das, who was appointed to helm the RBI in 2018, has been broadly praised for his stewardship of India’s economy and his management of the rupee, which has remained largely stable thanks to regular central bank interventions in the market.

Indian media have suggested that Das’s mandate is likely to be extended, which would make him the longest-serving RBI governor since the 1960s.

Das’s reappointment would mean “policy loosening is not on the cards for the time being”, said Shilan Shah, deputy chief emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, calling the RBI governor “one of the more hawkish panel members in recent months”.

“That all said, there is growing evidence that the economy is cooling and we still think that inflation will drop back over the coming months,” Shah added. “That will open the door for policy easing to begin in April, regardless of personnel.”

Das declined to comment on a potential extension of his term. “I have a monetary policy [meeting] coming up, I think my mind is preoccupied,” he said.

Read the full article here