Nvidia’s purchase of a $5bn stake in Intel is not a good investment. That’s not a reflection of Intel per se. It’s perfectly possible that the US chipmaker’s shares, currently just half of their peak, could perform marvellously in the coming years. But listed businesses taking small stakes in each other is almost always a poor use of shareholders’ capital.

Companies that invest in their peers are doing something shareholders can do themselves. Nvidia bought stock at slightly below the prevailing market price. It has not claimed any special perks for its money: no board seats, no unusual voting rights. Its 4 per cent stake will be too small to stop a takeover of Intel by another, should such a thing ever present itself.

The best thing that can be said about the investment, which accompanied a pledge to make chips together, is that it’s so small that Nvidia shareholders won’t care. The company, which makes the go-to silicon for the artificial intelligence boom, had roughly $57bn of cash and easily-sellable securities on its balance sheet at the end of July. Its investment needs are minimal: its capital expenditure last year was just $3.4bn. And of course, next to Nvidia’s $4.3tn market capitalisation, the amount is a trifle.

True, gestures matter. After all, the importance of symbolism is why Nvidia chief Jensen Huang is making the investment in the first place: to show that Nvidia and Intel are aligned. Since it follows the US government taking a stake in Intel too, this also denotes Nvidia’s alignment with the political elite. Nor is it the only one spending shareholders’ money on making a statement. Goldman Sachs is buying $1bn of stock in fund manager T Rowe Price to cement their new partnership — another indication of shared interest.

Perhaps the most troubling thing about Nvidia’s investment is that it is totally in line with the free-spending financial zeitgeist. Tech companies are allocating escalating amounts to capital expenditure, and investors are largely uncritical. Five of them — Alphabet, Amazon, Meta Platforms, Microsoft and Oracle — are expected to spend $500bn a year by 2028, according to S&P Capital IQ.

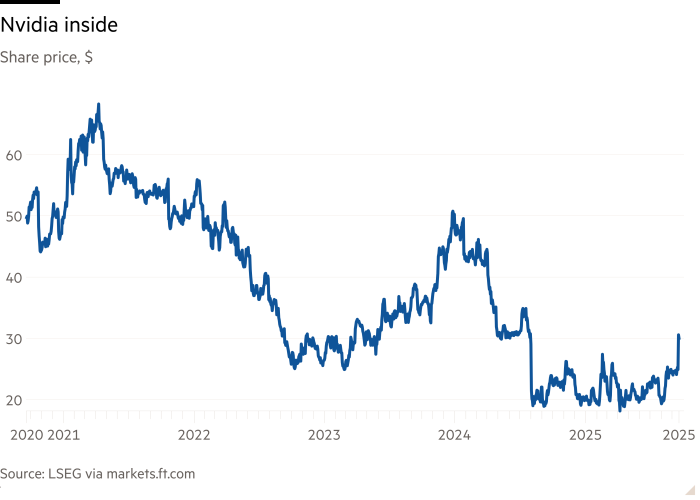

Huang no doubt feels validated by the market’s response to his investment. The rise in Intel shares in response to the Nvidia partnership, an alliance that should make sense even without a shareholding, already spawned a 29 per cent on-paper profit. But there’s a difference between exuberance and genuine value creation. In a downturn, investors want CEOs to be penny-wise; for now they can be as pound-foolish as they wish.

Read the full article here