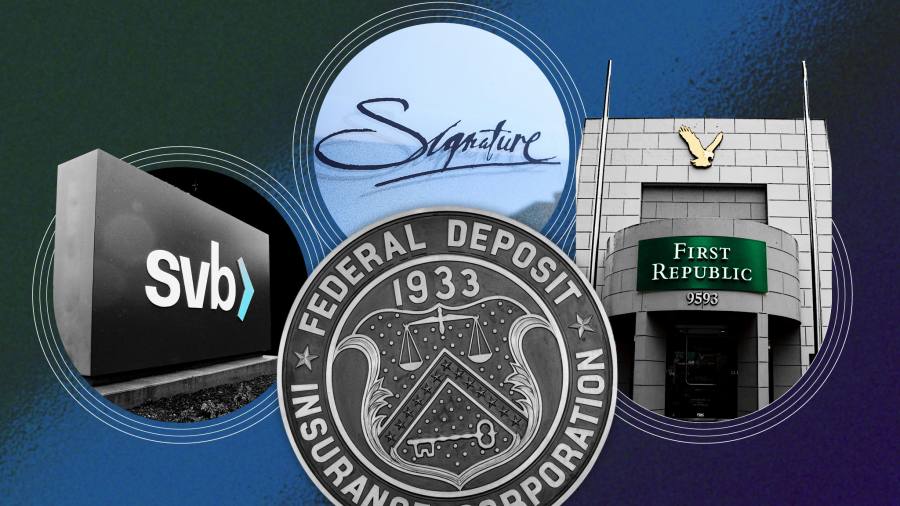

Although the March 10 collapse of Silicon Valley Bank helped spark First Republic’s implosion on Sunday night, US regulators took a markedly different approach to cleaning up the mess this time around.

When SVB failed in March, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation — the agency that manages US banking collapses — shut it down in the middle of a work day before it had lined up a potential buyer. That meant it had to set up a so-called bridge bank run by regulators until it brokered a sale of SVB more than a fortnight later.

Fears over what would happen to SVB customers with deposits above the $250,000 level covered by federal insurance had sparked runs at several other banks. That forced the Biden administration to declare that SVB and Signature, another lender that failed at the same time, were a systemic risk, allowing it to guarantee all deposits.

Conversely, First Republic had been teetering for weeks and the FDIC was able to take the bank into receivership and quickly broker a deal with JPMorgan to take on all the deposits — including accounts with very large balances.

This is the FDIC’s preferred playbook for closing banks. JPMorgan will pay $10.6bn to the regulator while the FDIC will provide JPMorgan with a $50bn five-year fixed-term loan. The agency estimates the deal will cost the insurance fund $13bn.

Why was JPM allowed to buy First Republic?

Under normal circumstances JPMorgan, the largest US bank, would been forbidden from buying First Republic on competition grounds. US regulators are not allowed to approve any deal that results in an institution holding more than 10 per cent of insured deposits in the US.

JPMorgan already sat above that threshold. However, regulators had an obligation to sell the bank to the party making the best offer for the FDIC. One person briefed on the transaction said JPMorgan had “received a waiver because it was by far the best deal”.

The ultimate decision to waive the rules was taken by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, an independent bureau within the US Treasury that ensures lenders comply with laws and regulations, according to Jeremy Barnum, JPMorgan chief financial officer.

Was this a ‘private sector’ solution?

Not quite. While the government’s fingerprints are harder to find on First Republic than other recent bank failures, it would be wrong to argue it was resolved by industry alone.

Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan chief executive, on Monday said his institution had switched sides from adviser to First Republic to buyer only after the government asked the bank to “step up”. And the final deal included the $50bn line of credit for JPMorgan as well as a loss-sharing agreement with the FDIC.

What’s more, First Republic’s failure and sale to JPMorgan will result in a loss of $13bn to the FDIC. Had it not taken the hit, some depositors — including large banks that had parked $30bn in First Republic as part of an ill-fated rescue attempt — would have lost money.

JPMorgan on Monday morning said it expected the deal to result in a slight immediate net gain for the lender. Had it completed a transaction without government assistance, it would have had to recognise billions of dollars of losses on day one.

Why did the Biden administration take a back seat?

In the weeks since the failures of SVB and Signature, top Biden administration officials had become increasingly confident that a flight of deposits from small and midsized lenders had started to stabilise.

First Republic was an exception that had to be dealt with. But the White House, Treasury and Federal Reserve — all of which were heavily involved in the other two banking collapses — took a more hands-off approach. Instead, regulators at the FDIC were firmly at the forefront of deciding the fate of the latest fallen lender.

Officials had wagered that there was less of a risk of broader contagion this time. The Treasury did not have to invoke the system risk exception because all of the deposits have been assumed by JPMorgan.

Less involvement from top officials could help shield the administration from any political backlash, including claims that the deal has further strengthened JPMorgan, a bank already deemed to be too powerful by some leftwing politicians and campaigners.

“All depositors are being protected, shareholders are losing their investments,” Joe Biden said in the Rose Garden of the White House on Monday. “Critically, taxpayers are not the ones that are on the hook”.

Has there been much political fallout?

In the aftermath of SVB’s implosion, Republicans criticised the FDIC’s decision to opt at first for a government-led solution and asked whether a bias against big banks getting bigger had helped scupper a sale.

So far, Republicans have been more complimentary about the First Republic resolution.

“I’ve long expressed concerns over broad, taxpayer-funded government intervention, so I’m glad the FDIC heeded my concerns and secured a private market solution for First Republic,” said Tim Scott, the top-ranking Republican on the Senate banking committee.

Republican Patrick McHenry, chair of the House financial services committee applauded the “quick work of regulators”.

Meanwhile, progressive Democrats seized on the failure of another US bank to bolster their calls for tougher regulation, including more robust capital and liquidity requirements. Sherrod Brown, the Democratic chair of the Senate banking committee, said First Republic’s collapse showed a need for “stronger guardrails”.

Progressive Democratic senator Elizabeth Warren said the failure of First Republic underscored “how deregulation has made the too big to fail problem even worse”.

“A poorly supervised bank was snapped up by an even bigger bank — ultimately taxpayers will be on the hook,” she added.

Read the full article here