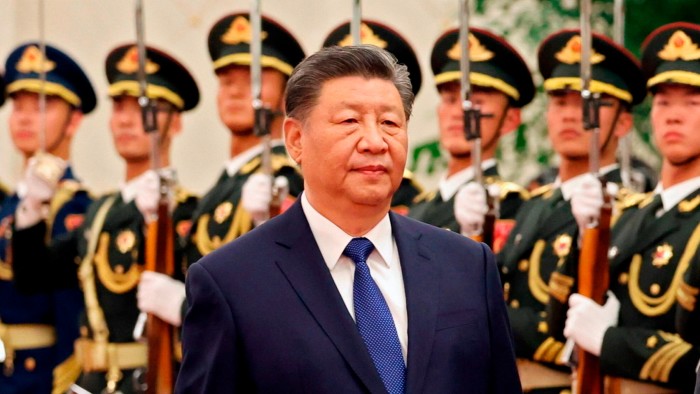

Chinese leader Xi Jinping is under heightened pressure to better secure his country’s interests in volatile regions around the world after a bomb attack by Pakistan separatists last month claimed the lives of two Chinese engineers.

With total Chinese investments estimated at US$62bn, the China Pakistan Economic Corridor is the largest cluster of projects under Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative but a spike of violence by the Balochistan Liberation Army is putting that commitment at risk and fuelling debate over Beijing’s failure to get to grips with the problem.

While Chinese investors are protected by a mix of Pakistan government and Chinese private security, the latter is hindered by Pakistan’s ban on armed guard services by foreign security contractors and Beijing’s tight grip on military and policing functions, even overseas.

“I think this is the tipping point where Beijing is demanding something more from Islamabad in terms of a Chinese role in providing security,” said Alessandro Arduino, an expert on BRI security and private security contractors.

“The evolution in Pakistan will also be a litmus test for Chinese private security companies around the world, and how Beijing wants to secure its citizens and assets worldwide.”

Islamabad has allocated big and growing forces to guarding China’s massive investments. Two special security divisions with more than 15,000 personnel in total and a naval unit stationed at Gwadar port protect CPEC projects and Chinese workers throughout Pakistan. Provinces have also provided special police units. Part of the cost of this protection is covered by China’s defence ministry, according to two people familiar with the situation. But it has not produced the security China is hoping for.

“We don’t trust that more Pakistani soldiers will keep us safe . . . we would prefer it was Chinese,” said one Chinese businessman, who works on a project in the province of Punjab but has been in the country for almost a decade. “Many Chinese want to leave, there’s not as much opportunity and the security is bad.”

Those concerns were further underscored when a Pakistani security guard shot and injured two Chinese workers in Karachi last week.

Beijing is not content with local security either. “The central government issued an internal directive to ‘let Chinese take care of the security of Chinese’,” said Zhou Chao, a Chinese executive who managed security services for the Lahore Metro Orange Line project after China Railway Group and Chinese arms exporter Norinco won the tender in 2015.

Chinese private security companies have typically followed state-owned enterprises to guard their construction and resource projects abroad. Some observers expected them to grow into the equivalent of US military contractor Blackwater or Russian mercenaries Wagner Group, but Chinese experts say they are held back by a lack of support from Beijing and complex regulation.

Pakistan bans foreign security contractors from providing armed guard services. “As a solution, we would station Chinese security officers at the project company, two at a time, and hire 400 to 500 local guards,” said Zhou, who worked for China Cityguard at the time but has since moved to China Soldier Security Group.

Other executives said they relied on Chinese security engineers to develop a security plan, handle incidents, conduct background and document checks, gather intelligence and hire local guards for armed patrols.

The October blast, the latest in a string of attacks, has fuelled discontent with the current security set-up. “Our government has been discussing with Pakistan whether they can allow Chinese security companies in but have been explicitly rebuffed several times,” said a Chinese executive.

In a joint statement with Pakistan during Chinese Premier Li Qiang’s visit on October 15, China “stressed the urgent need to adopt targeted security measures in Pakistan to jointly create a safe environment for co-operation between the two countries”. Last week, Chinese ambassador Jiang Zaidong called it “unacceptable” that Chinese citizens had been attacked twice within six months. He warned that security had become a “constraint to CPEC”.

While overall Chinese finance and investment engagement under the BRI increased last year, according to the commerce ministry, it dropped 74 per cent in Pakistan. Frontier Services Group, the security contractor backed by Blackwater founder Erik Prince, said in its 2023 annual report that due to the instability in Pakistan, the Chinese government had encouraged employees of Chinese companies in Pakistan to return home. This has led to delays and abortion of projects.

“The government is failing to comprehensively solve this security problem. [Our] risk consultants in Pakistan warned us about certain things, which later really happened, and I don’t know why our government could not prevent those,” said an executive at a large Chinese security company.

A big hurdle is the belief of the Chinese Communist party — which came to power through armed revolt — that it must retain a strict monopoly on military and policing functions. Beijing keeps tight restrictions on private security companies at home including a ban on carrying arms. Although existing legislation does not explicitly cover the contractors’ overseas expansion, it has hampered them.

According to Cheng Xizhong, a South Asia expert at Chinese think-tank Charhar Institute and former diplomat and defence attaché who also advises Chinese private security contractors, the Chinese embassy in Islamabad has a police counsellor telling security companies in Pakistan what should and should not be done.

“Some people see Chinese security contractors who go abroad as proxies for the Chinese People’s Liberation Army,” said a security company executive. “But unlike international military contractors that thrive on government contracts . . . we don’t get any . . . support.”

The latest uptick in casualties could add to pressure on Beijing to update legislation regulating private security companies. Amendments are expected to include clearer reference to overseas operations and be guided by an international code of conduct for the industry, according to scholars consulted on the draft amendments.

“A large portion of our overseas investment flows into” countries that it deems high risk, said the founder of one Chinese private security contractor. “So it really is high time that our government empower us to expand there.”

Additional reporting by Tina Hu and Wenjie Ding in Beijing

Read the full article here