Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

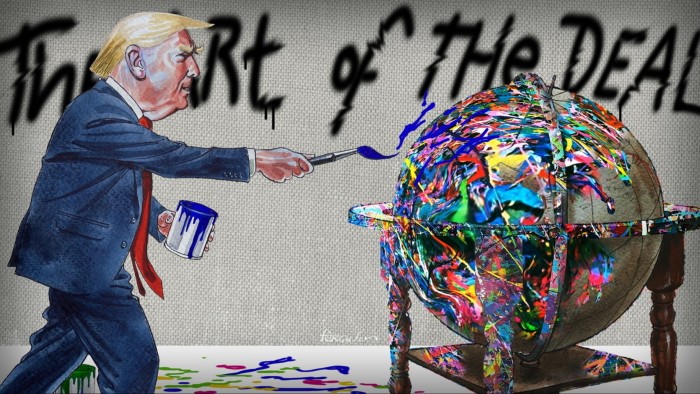

Donald Trump’s 25 per cent tariffs on Canada’s and Mexico’s exports, along with the 10 per cent tariff on China’s, change the world. This is true even though tariffs on the first two countries have been temporarily lifted. We know that, under this president, the US recognises only its own narrow interests as legitimate. That makes it bad. But, worse, its view of its interests is mad. The combination makes it a dangerous partner for other countries to trust.

In Trump’s view, running a trade surplus with another country is a “ripoff”. This is of course the reverse of the truth: such a country provides a greater value of goods and services to US customers than it receives from them. Its residents will either be using this surplus to pay countries with which it is running deficits or be accumulating financial claims, mainly upon the US, because the US is a safe place to invest in and issues the world’s reserve currency. A way to reduce US trade deficits then would be to cease providing highly regarded assets. The inflationary impact of Trump’s fiscal and monetary policies might even achieve that. Yet Trump is determined to retain the dollar’s reserve status. Paradoxically, then, he wants the dollar to be both weak and strong.

Trump’s naive focus on bilateral balances rather than the overall balance (unlike the mercantilists of old) is ridiculous. But it is a reality. So, he is using the threat of tearing up the US -Mexico-Canada Agreement he concluded in his first term to impose penal tariffs. Astonishingly, these tariffs are to be much higher on Canada, with which the US has the longest unguarded border in the world, than on China, its proclaimed enemy. In any case, we now know that being a close ally will not influence Trump. Like any bully, he will menace those he considers weak. It might not end there. Sounding like Vladimir Putin on Ukraine, he has indicated he would like to annex Canada. This is a sick joke. Why would Canadians, with far higher life expectancies and lower murder rates, wish to become Americans?

While Trump plays his games, we must ask what the implications of such tariffs might be? An analysis by Warwick J McKibbin and Marcus Noland for the Peterson Institute for International Economics concludes that 25 per cent tariffs on Canada and Mexico and 10 per cent tariffs on China, against which the latter retaliates, would hurt all four countries. But they would hurt Canada and Mexico more than the US, lowering Canada’s GDP by a little over one percentage point relative to what it would otherwise have been. Would this be enough to persuade Canada to give up its independence? No. At the same time, according to Kimberly Clausing and Mary Lovely of the PIIE, “Trump’s tariffs would cost the typical US household over $1,200 a year”.

Trump claims that Canada is a major source of fentanyl. But, according to a recent story in The New York Times, “the quantities of fentanyl leaving Canada for the US are . . . 0.2 per cent of what is seized at the US southern border”. Instead of bullying Canada, the US might instead ask itself why so many Americans are addicts.

Douglas Irwin puts these tariffs in a broader historical context in a note, also published by the Peterson Institute. If these tariffs were implemented, it would increase the average tariff on total imports from 2.4 per cent to 10.5 per cent, an increase of 8.1 percentage points. It would also increase the average tariff on dutiable imports from 7.4 per cent to 17.3 per cent, an increase of 9.9 percentage points. This would bring US tariffs to levels not seen since the early 1950s. More could follow.

A crucial objection to what Trump is doing is the uncertainty he creates. The decisions by Canada and Mexico to enter a free trade agreement with the US, just like other countries chose to open their economies within the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the World Trade Organization, were bets on policy stability. This is important for countries, especially small ones, and vital for businesses betting on reliance on foreign markets and integration into complex supply chains. Even unfulfilled threats are damaging. An inconsistent US is an unreliable partner: it is that simple.

It was not always so. Before Trump killed the WTO dispute settlement mechanism in 2019, countries used to bring and win cases against the US. The rules-governed order was not a fantasy. But it is now — thanks to Trump.

The economics are at the heart of Trump’s abuse of the tariff weapon. But it is about far more than economics. The unpredictability of the US affects every aspect of its international relations. Nobody can count on it, be they friend or foe. So, nobody can make plans based on reliable assumptions about how it will behave in future. It is possible that some allies will decide that, although they prefer the US, China is at least more predictable. That would be an insane position for these countries to be in. But it would be the almost inevitable result of Trump’s gangsterish approach to international relations.

For the closest allies, such as the UK, the situation is particularly grim. The alliance with the US has been the foundation of its security since 1941. Can it assume that this will remain the case? What are the alternatives? Is there, more broadly, a notion of a stable and committed western alliance left?

Meanwhile, what are Trump’s victims to do? Chrystia Freeland, former finance minister of Canada, suggests Ottawa should threaten 100 per cent tariffs on Teslas. But as Tim Leunig, a British economist, notes, Trump does not care about Tesla. Canada should instead threaten taxes on exports of oil and electricity. If the US threatens friends, the latter must stand up to it. That is how to deal with bullies.

Follow Martin Wolf with myFT and on X

Read the full article here