World leaders are expected to make their strongest pledges to tackle dementia for 10 years at the G7 summit in Hiroshima, as degenerative brain diseases impose a growing burden on the global economy and effective treatments for Alzheimer’s begin to emerge.

Japan’s government hosted a meeting of global dementia organisations in Nagasaki on Sunday ahead of the summit beginning on May 19. Tokyo hopes the conference will pave the way for an updated declaration, matching the scope of the commitments made at the G8’s London summit in 2013.

The declaration is likely to include commitments such as increasing funding for research, improving access to care and increased international co-operation to address Alzheimer’s disease and some of the 100 or so less common forms of dementia.

“The London summit made historic commitments to improve the lives of people affected by dementia and to speed up development of disease-modifying drugs,” said Lenny Shallcross, executive director of the World Dementia Council, which was set up in 2013 to help governments meet those commitments.

“Today governments need to address different challenges, now that we have the first disease-modifying drugs, biomarkers that could show who could benefit from them and citizens who will expect to be treated,” he said.

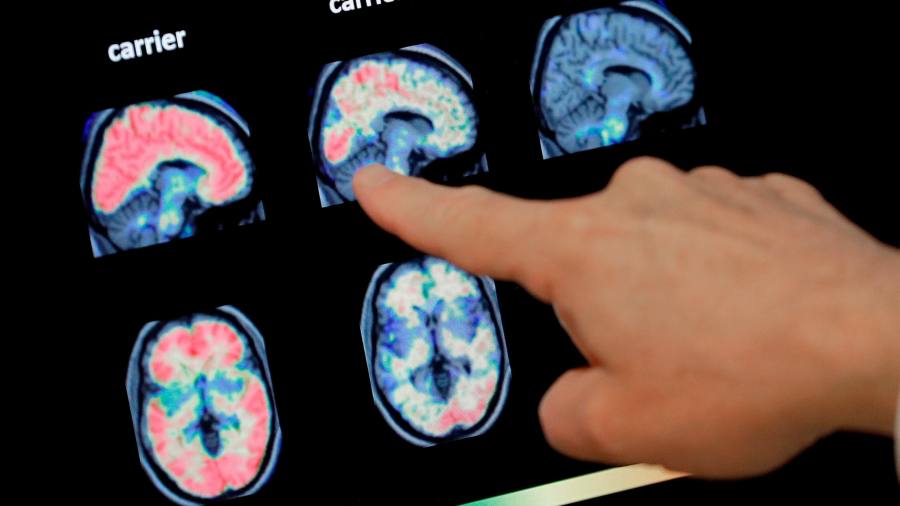

The first two drugs shown in clinical trials to slow the progression of the disease — donanemab from Eli Lilly of the US and lecanemab developed by Japan’s Eisai with US biotech Biogen — reduce the build-up of sticky amyloid proteins in the brains of people suffering Alzheimer’s.

A survey of the Alzheimer’s drug development pipeline in 2022 by Jeffrey Cummings and colleagues at the University of Nevada showed companies and academic labs globally are working on 143 medications with a wide variety of different mechanisms besides targeting amyloid.

Japan takes a particular interest in dementia, as it has one of the world’s oldest populations with about 30 per cent aged above 65.

“The summit in Japan will allow us to shine a spotlight on dementia, which has become the first or second leading cause of death in five of the seven G7 members,” said Paola Barbarino, chief executive of Alzheimer’s Disease International, a federation of dementia associations. She added that 60 per cent of healthcare practitioners “think incorrectly that dementia is not a disease but part of normal ageing”.

George Vradenburg, founding chair of the Davos Alzheimer’s Collaborative, an international foundation promoting innovation in dementia treatment, said the 2013 G8 summit had an initial galvanising effect on the field but the longer-term response was inadequate.

“I’m disappointed that governments didn’t follow through with a more co-ordinated approach,” he said.

Only the US government carried through with a large and sustained increase in Alzheimer’s research funding, rising tenfold from $400mn to $4bn a year over a decade, Vradenburg said. “Publicly funded research must be increased everywhere, including low and middle-income countries, to provide a base for the pharma and biotech industry to develop new treatments.”

Inclusion of dementia in Japan’s G7 agenda “shows governments shining more of a spotlight on the issue”, Shallcross said. Another high-level conference has been organised by the government of the Netherlands for the autumn.

“We will continue to work closely with our G7 partners on dementia research and innovation. If we are to develop new treatments, and provide better dementia care . . . international collaboration is crucial,” UK health secretary Steve Barclay said at the Nagasaki conference.

Dementia will also feature prominently at the World Health Assembly next week, Barbarino said. The Geneva meeting will address the failure of most World Health Organization member states to develop national plans for dementia as agreed in a global action plan in 2017.

“Inaction means that health systems are not prepared, despite emerging treatment breakthroughs, leaving millions unable to access the care and support they need,” she said.

Read the full article here