In the spring of 1989, a train heaving with students arrived in Beijing. Its carriages were so packed that occupants had crammed themselves into luggage compartments and under seats. Once in the Chinese capital, they spilled on to the city’s streets to take part in pro-democracy protests sparked by the death of a popular reformist leader. One of the passengers was a 23-year-old named Li Lu.

Li, a slender, bespectacled student from Nanjing University, had boarded without a ticket. He was trying to blend into the throng of people exiting the station in Beijing when a man in uniform stopped him. Li feared the worst, but the ticket collector merely waved him through, signalling his support for the protesters by making a V sign with his hand and smiling. Grateful for the reprieve, Li followed the crowd towards Tiananmen Square.

The scale of the square is hard to appreciate without seeing it first-hand. It is so vast that, on a normal day, The Gate of Heavenly Peace appears to sit on the horizon in the far distance. The day Li arrived, it was filling with masses of human beings demanding freedom. Protesters wanted political reform, and some were prepared to starve themselves for it. Demonstrations lasted for months, during which students organised themselves into factions and held leadership elections. Despite not hailing from one of Beijing’s pre-eminent institutions, Li won a seat. He represented the radicals.

Li was born in April 1966. Soon after, his parents were sent to labour camps as a consequence of Mao Zedong’s cultural revolution. Li spent his childhood bouncing between caretakers and an orphanage. By the age of 10, he’d survived a catastrophic earthquake in Tangshan, which official records show killed 240,000 people, including all the members of Li’s adoptive family.

Though experiences like his were not uncommon among his generation, Li knew many students at Tiananmen saw him as an outsider. He didn’t bother trying to win over doubters with rousing speeches, preferring instead to work as a power broker. Wang Juntao, one of the protest organisers, watched as Li mostly remained silent during meetings, absorbing differing views. According to Wang Juntao, Li also made sure to get close to the right people. He quickly became friends with Wang Dan, a student leader from Peking University, and impressed Chai Ling, chief commander of a student group calling itself Defend Tiananmen Square Headquarters. Chai, who was more radical, nominated Li as one of her vice-commanders.

Some student leaders had spoken to Wang Juntao about Li, wondering why he’d arrived in Beijing without any ties to the organisations behind the movement and why he wasn’t carrying identification. They wondered if Li was a spy. A veteran of past protests, Wang Juntao shrugged off their suspicions. But Li did seem different. When they shook hands at their first meeting, the older activist felt in Li’s grip the rough hands of a manual labourer, not a scholar.

Wang Juntao preferred to focus on what he saw as the important role Li was playing in the students’ decision making. Most of them hoped to negotiate with the government in order to achieve political reform in China. Not only did Li not trust authorities to honour a deal, but he always seemed to advocate the most aggressive methods to hold their attention. He played a pivotal role in orchestrating a six-day hunger strike in mid-May which galvanised public sympathy but also provoked the ire of the government.

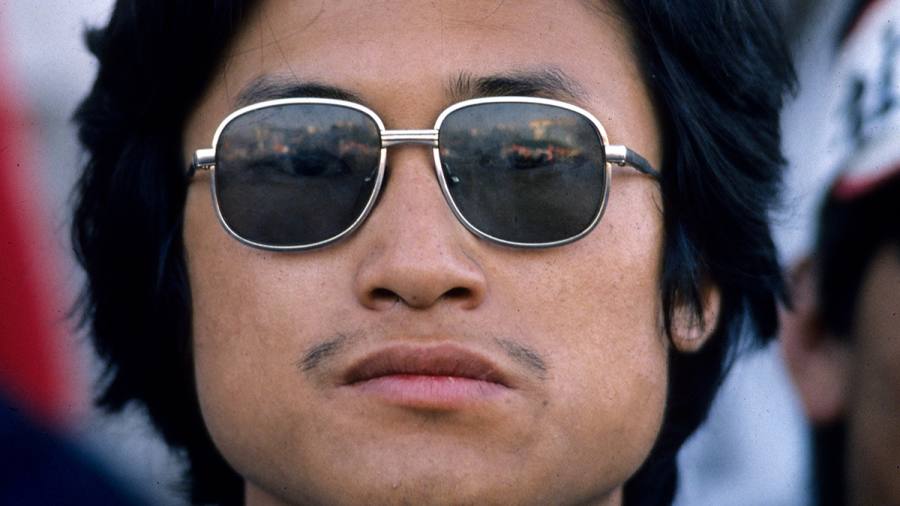

When protesters’ morale began to sag, Li announced that he and his girlfriend were going to get married in a symbolic public ceremony. In photographs from that day, Li is dressed in a scruffy tank top and boxy aviators, a revolutionary banner hanging skew-whiff around his neck. Friends cheered the happy couple with cheap liquor and a cappella wedding songs, and the stunt’s overtones of joy and hope re-energised the crowds.

By late May, one million people were amassed in the square. As the police and military presence around them intensified, some students feared the army was preparing to move in to vacate the square. Chai and Li’s camp wanted to stay. Then, in the early hours of June 4, troops marched in, opening fire on activists. Tanks crushed tents with sleeping protesters inside and blocked exit routes, while soldiers arrested those who tried to flee. Officials claimed 200 civilians were killed; student leaders estimated the figure at up to 3,400.

In the aftermath of the massacre, the government named 21 students wanted for leading the uprising. Li, his mop of shaggy black hair and oversized sunglasses plastered across state media, went into hiding. Using a smuggling route established to bring contraband western goods from Hong Kong, then still a British colony, he managed to escape. Wang Dan and Wang Juntao were not so lucky. Although Li had his freedom, he was a wanted man. By the time he finally returned many decades later, he had a profoundly more complicated relationship with the Chinese state and hundreds of millions of dollars at his command.

In late-1989, Li was granted asylum in the US. New York was difficult for someone who had never been outside communist China. With no money and no English, Li depended on the generosity of people in human rights circles who admired the stand he and other students had taken. Robert Bernstein, a prominent human rights activist and chief executive of the publishing giant Random House, helped him get settled. Another campaigner, Trudie Styler, gave him a bag of second-hand clothes. They belonged to her husband, rock star Sting. Styler later produced a documentary based on Li’s life story.

Li declined to be interviewed for this article. His company, Himalaya Capital, made some executives available to shed light on the evolution of his thinking over the years.

Li’s 1990 memoir, Moving the Mountain, describes the tumultuous events of his early life in China. In an interview some years later, he summarised how they’d shaped his outlook: “I tried to identify with any family that took me in and learnt to fit into whatever environment I found myself,” he said. In New York, he was in a similar situation. He learnt English over the course of a summer, before enrolling at Columbia University, where he eventually became one of the first students to simultaneously earn an undergraduate degree in economics and graduate degrees in business and law. In class, his quiet authority and probing questions impressed others. “He was not hampered by deference to the professor like many other students are,” said one former teacher. “You got the sense he was moving somewhere.”

The question was, where? As an activist, Li had drawn attention to Wang Juntao’s plight by staging a 15-day hunger strike outside Congress in 1991. But by the mid-90s, the spotlight on Tiananmen was already beginning to fade, as more and more dissidents were being allowed to leave China. After arriving in the US, “I always had this fear in the back of my mind of how I was going to make a living here,” Li told a student group many years later. And, at Columbia, he got a crash course in American capitalism. After attending a lecture given by Warren Buffett, Li started investing his student loan in the stock market, making significant returns.

By the time he graduated in 1996, Li had successfully integrated his student activism with the need to earn a living. He’d become well known among New York A-listers with an interest in human rights, his graduation earning him a short profile in The New Yorker. Wall Street institutions queued up to offer him a job. But within a year, Li opened his own hedge fund instead.

Hedge funds were booming, riding the 1990s economic surge in the US with ever more creative and risky investment strategies. Managers such as John Paulson, Steve Cohen and Ray Dalio became stars, and Li aspired to reach their ranks. It was practically unheard of for a fresh college graduate to strike out on their own, let alone to court high-profile investors such as Jerome Kohlberg, co-founder of the renowned private equity buyout firm KKR. But most graduates didn’t have Li’s life story. The decision to invest with him, Kohlberg told The New York Observer at the time, “wasn’t my usual cautionary thing, but my admiration prevailed”.

The hedge fund, Himalaya Capital, got off to an inauspicious start. He had sought opportunities in Asia but, after the 1997 financial crisis in the region, Himalaya lost 19 per cent of its value in its first year. One of its largest investors withdrew not long after. Li soon tired of day trading and short selling, which exposed him to unlimited downside risk and could spell the death of a small fund if a target stock soared. Taking stakes in Japanese and Korean stocks that had been battered by the crisis helped Li recover and, by the mid-2000s, he had around $100mn under management. His one-man shop started hiring.

Li’s background made him a unique figure in US investment circles — the Chinese dissident who was making a fortune by adopting western capitalist values. The pivot from “freedom fighter to Manhattan yuppie” as one newspaper put it, was bound to raise eyebrows. In 1989, he’d chastised American government officials who visited Beijing for their “cynical determination to do business with China”. Now, Li embraced his change in philosophy, talking openly about a long-term strategy to invest in China’s growth and extolling the democratising effects of the newly emergent internet. He was also making connections with other Chinese immigrants. Among them was Xiong Wanli, a real-estate tycoon who he met in Los Angeles at the end of the 1990s.

In 2003, Li was invited to Thanksgiving lunch at the Santa Barbara home of a woman he’d met through human rights work. The host’s husband was a director at Berkshire Hathaway, the conglomerate Buffett built up as he became the most successful investor in the history of capitalism. Charlie Munger, Berkshire’s vice-chair and Buffett’s right-hand man, was there too. Munger and Li struck up a conversation about stocks and were still talking a few hours later. It was the beginning of a partnership that would last 20 years. “He was a very intelligent, self-confident young man,” says Munger, who is 99 and still vice-chair of Berkshire. “He so liked being a principal instead of being an agent working for somebody else. That was immediately obvious to me and, of course, that’s how I am. So, I naturally had considerable sympathy for him. I tried to get him to work at Berkshire, but I was fighting against nature.”

Li’s drive impressed Munger. “I’m not interested in revolution,” he says. “I’m a capitalist. It was his capitalist aptitude that attracted me, not his revolutionary history.”

At the outset, Munger advised Li to fully remake himself as an investor in the Buffett mould. This meant ditching adrenaline-fuelled trading in favour of a longer-term form of “value investing”. Buffett’s approach emphasised funding undervalued assets that could be cultivated to grow over decades. Li had arrived from China with a very different view. “My impression of the stock market was that of Shanghai in the 1930s as depicted by Cao Yu’s play Sunrise — full of cunning deceits, luck and bloodshed,” he wrote years later in a foreword to the Chinese edition of Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T Munger. Adopting the Buffett philosophy, Li’s mantra became “accurate and complete information”. Complete sometimes meant going to extraordinary lengths to get a read on the CEO of a company being researched by Himalaya, such as by attending their church or talking to their neighbours, according to contemporaneous articles.

After Li started a new fund in 2004, Munger entrusted him with $88mn of family money. It was a boon to the young Chinese money manager, who would have otherwise had to hustle to fundraise while demonstrating monthly returns. “We made unholy good returns for a long, long time. That $88mn has become four or five times that,” says Munger. For example, Li bought Kweichow Moutai early. The brand of distilled liquor became the official national libation shortly after the communist revolution. As China boomed, Moutai became the drink of choice for toasting foreign dignitaries and the bribe of choice for high-ranking bureaucrats. As a stock pick, it is legendary in Asian investment circles, akin to buying Apple in the late-1990s. At times it’s been the biggest listed company in China. “It was real cheap, four to five times earnings,” says Munger. “And Li Lu just backed up the truck, bought all he could and made a killing.”

Every June brought the painful anniversary of Tiananmen. Wang Dan, who topped the Chinese government’s wanted list, spent much of the next nine years in prison before he was finally granted asylum in the US in 1998. Li’s fellow activist had played a starring role in his autobiography. Wang Juntao, the older man who’d noted Li’s hands, was sentenced to 13 years for conspiring to subvert the government. After a harrowing escape from China, Chai Ling had landed in the US and gone on to earn an MBA from Harvard. (She did not respond to interview requests.)

For the anniversary in 1999, an American news network tracked down some of the “heroes of Tiananmen”. Wang Dan said his first priority was to rejoin the campaign for change in China from his exile in the US. “My dream is that I can do something,” he said. Chai, the former radical who had been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990, was blunt: “Being a political activist is not going to change China, let’s just face it. We tried 10 years ago. We had millions of people with us. It didn’t work.” Li struck a different note. He still called himself a dissident, but admitted he had largely withdrawn from political activism, telling the interviewer it was “unrealistic” to continue demonstrating on the streets of New York.

Wang Juntao is now 65. He still refers to himself as a “professional revolutionary”. Speaking over the phone earlier this year from his office in Flushing, New York, he explained how the life of a dissident is in some ways simple, despite the considerable personal costs. “If you want to be a hero, it is easy to sacrifice yourself,” he said. By contrast, those who follow a path like Li’s have to be “complicated”. “You have to balance a lot of things.”

Roughly beginning with China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, the idea that free-market capitalism would democratise China had a good run. Though Li was still a political pariah in Beijing, his success in business made him look like a natural bridge between the two countries. As KKR’S Kohlberg put it in 1998, “I would like to see him succeed and eventually help bring China into the 21st century and be a democracy, and I think he, by then, will be uniquely qualified.”

Himalaya’s biggest early success bolstered that notion. In 2002, Li invested in BYD, then a little-known maker of electric batteries. Though he was still ostensibly forbidden from visiting the company’s factory in Shenzhen, he believed that the future lay in the manufacturing might of China and in the purchasing power of its 1.4bn consumers. He sold Munger on his vision, with Berkshire taking a 10 per cent stake in BYD in 2008. “I didn’t like the auto business,” Munger recalls. “It’s difficult to make a fortune in the auto business.” But, “it worked so well, the early investment in BYD was a minor miracle”. The company dethroned Tesla as the world’s biggest electric vehicle producer by sales last year.

Whether it was obvious at the time or not, the apotheosis of the idea that trade would lead to a freer China occurred on August 8 2008, during the opening ceremony of the Olympics in Beijing. By then, China was the world’s third-largest economy and growing. In the run-up to the Games, human rights groups tried to highlight government abuses against Tibetans and the persecution of the religious sect Falun Gong. But calls for boycotts resulted in little. After the Games, western politicians and executives flew into the country to sign trade and investment deals. The rush of foreign capital was only intensified by the meltdown in western economies caused by the unfolding financial crisis. “It’s when they forgot the June 4 massacre,” says Wang Juntao. “After 2008, if you are an enemy of the Chinese government, it is impossible to collect money from Wall Street.”

These macro forces created divisions among formerly tight-knit dissidents. But, when Wang Juntao first arrived in the US, he and Li met for coffee and to talk about China’s future. Their relationship changed after he graduated from Columbia in 2006 and travelled to New Zealand to continue his studies. Attempting to return to China in 2007, Wang Juntao was informed by the government that he would not be allowed back. “They said if I stayed in China, my life will be trouble.” He returned to the US in 2008 but hasn’t seen Li since. “I understand. No matter what decision he made,” he says. “I don’t need him, and if I approach him then I will disturb his road. Even if we have a cup of coffee and the Chinese government knows it, then the government will think it’s too much.”

Sitting on a brown leather sofa in the club bar of Fort Lauderdale Country Club in Florida, Xiong Wanli says that in 1990s-era China, “making money was really too easy”. Xiong had also attended the Tiananmen protests but, in the years that followed, he stayed in China, like most from the “class of 89”. After Tiananmen, he moved to the former fishing village of Shenzhen, which was being transformed into a sprawling metropolis. Its population today is 17.6mn, bigger than New York’s.

After working for several years at a state-owned developer, Xiong founded his own real-estate company, with the aim of leveraging the connections he had made with local and central government officials on the golf courses springing up around Shenzhen. These were the days before Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption crackdown, when close ties between politicians and executives were an accepted reality of doing business in China. “There was so much land back then,” Xiong says. He got rich in the accompanying real-estate boom.

In 2002, Xiong moved to the US to pursue a master’s degree at Harvard. He recalls how private wealth managers chased him around after he arrived, while casinos flew out private planes to take him to Las Vegas. He also believed that prosperity would be a liberalising influence in China. He’d met Li on a golf course. The two invested in Duowei, a Chinese-language media site founded by an exiled journalist named Ho Pin. The site pitched itself as the critical media that would be prepared to enter China once the country liberalised. Despite being banned in China, its scoops made it a thorn in Beijing’s side. Twice, it correctly predicted the line-up for CCP’s Politburo Standing Committee, China’s equivalent of a cabinet and a closely guarded secret in the run-up to the party congress held every five years.

Xiong saw it as an investment in China’s future. Duowei, catering to the millions of Chinese people living overseas who wanted a more critical voice than was served up by the domestic press, seemed like a good financial investment to Li. (Himalaya and affiliated investors owned just under 50 per cent of Duowei’s parent company.)

In April 2008, Duowei’s leadership team gathered for a routine board meeting. Xiong dialled in from Wuhan. Over the crackly line, he heard Li’s voice announce that he was selling his stake. The pronouncement shocked Xiong, who asked Li to sell him the stake instead. But Li sold to Yu Pun-Hoi, a Beijing-friendly media baron. Xiong says he suspects that Li sold to Yu to ingratiate himself and improve his chances of becoming a conduit for Wall Street in China. According to a Himalaya spokesperson, the decision to divest from Duowei was part of a broader wind-down of its venture capital fund; Yu’s bid was accepted as the highest offer.

In the years since, it has become clear that the idea that trade would create a democratic China was a fantasy. President Xi has consolidated his grip on power, purging political and business rivals in a crackdown billed as a populist anti-corruption drive. He abolished term limits in 2018. Beijing’s increasingly aggressive foreign policy and military posturing towards Taiwan, alongside its repression of minority groups at home, have prompted western governments and companies to distance themselves. Embracing aspects of market capitalism has led to a vastly more wealthy and powerful China but, ultimately, a more successfully authoritarian one.

Amid the changes, Duowei moved its headquarters to Beijing and, while it remained banned in China, the site became more cautious in its coverage of the regime. Last year, it shut down, citing financial difficulties.

In late September 2010, a blurry photograph taken on the leafy BYD campus in Shenzhen appeared in a Hong Kong newspaper. The picture showed rows of the company’s uniformed managers and government officials lined up behind famous guests from the US. Sitting in the front, clad in casual attire, were Microsoft founder Bill Gates, Buffett and Munger. At the end of the row sat Li, wearing a pair of dark sunglasses. Though its coverage of the trip mostly featured photos of Buffett, Chinese state media confirmed the reports of Li’s presence. It was the first case of one of the exiled students from the government’s list of 21 being granted re-entry.

China was keen to court foreign investors — and there were none more prominent than Gates and Buffett. Powerful allies in the US lobbied for Li to join the trip, according to a person involved, which helped smooth his passage. It was agreed that Li would avoid publicity. But sitting there, positioned between the US billionaires and representatives of Chinese power, Li looked like the bridge builder he’d been spoken of as 20 years earlier.

The experience was revelatory for Li. For one, he finally got to see inside his prized investment, BYD. Although China’s authoritarian regime remained in place, what Li saw of the economically transformed country validated his attitudes towards Beijing, according to the person who took part in the trip. “The protests accelerated the pace of reform,” this person argued. “Some of those demands turned into reality, although not all. Ordinary people’s lives have improved.”

Li made subsequent trips to China, visiting companies and delivering lectures on value investing at Beijing’s top universities. In 2014, he joined the microblogging website Weibo, where he posted on Chinese development and attributed its unprecedented economic rise in part to a governing party with “extraordinary executive power and talents”. He became something of a celebrity in Chinese business and finance, a revered example of a person born in the era of the cultural revolution who managed to become a success both in China and the US. In 2019, Li gave a seminar at Peking University, not far from the square where he had risked his life to achieve political change three decades before. In China, he carved out a new public persona, writing books about investing and essays on Chinese modernisation devoid of references to his student days.

To Wang Dan, the friendship forged with Li on the square in Beijing is now a distant memory. After the Clinton administration secured his release from China, Wang Dan became an academic. He says that he and Li were close friends for a time when Wang Dan was living in the US, meeting to discuss the prospects of Chinese democracy. He was one of the best men at Li’s next wedding. They grew apart after Wang Dan went to Taiwan to teach, ceasing communication entirely after Li’s first visit back to China. Speaking over the phone from his home in Maryland, he said Li had “chosen to co-operate with the government. He has the freedom to make this choice, but it isn’t a moral choice. Li’s wealth today is related to the Tiananmen Square movement. He benefited from that movement. It is very unethical to stand with the government officials who killed the students back then.”

Beijing has also reaped political dividends from Li’s transformation, Wang Dan believes. “The government needs to prove that the students in 1989 have admitted their mistakes,” he says, echoing Xiong’s criticisms. “They are using Li Lu as a model.” Since being interviewed for this article, Wang Dan has stepped down from a teaching post in Taipei, following accusations of sexual assault. He denies the allegations. A source close to Li Lu says he was able to raise money because of his track record of investing, beginning while he was at Columbia. “It was on this basis that he was able to build Himalaya Capital, not because he was a student protester.”

But Li’s mentality had changed. Over the years, he’d come to see himself as an immigrant rather than a refugee. “If you continue to view yourself as a political refugee, life is harsher,” says one person familiar with his thinking. “You’re dealing with a different reality where you still consider China as home . . . That is not an easy life.” Says Munger: “He’s changed. He was looking for a way to succeed mightily in the world. Li Lu is no longer a revolutionary. He’s a capitalist. You can’t find a more capitalistic capitalist than Li Lu.”

Visitors to Himalaya’s offices on the 21st floor of a tall block in downtown Seattle would be forgiven for thinking they’d stumbled into a library. Save for a rowing machine tucked in one corner, the office is missing some of the usual trappings of high finance. Bloomberg monitors do not tower over the analysts, nor are there TVs streaming financial news. Himalaya moved from Wall Street to Pasadena, California, in 2007, in order to be closer to Munger, before settling in the lower-tax Washington state in 2018. Each time, the office set-up was carbon copied from Berkshire Hathaway, where teams of analysts cover a handful of companies in detail and report directly to a central decision maker. “We all serve one purpose: to help Li Lu make investment decisions,” says Gene Jing Chang, Himalaya’s COO and longest-serving employee, after Li.

The firm currently manages $14bn of assets. In contrast to his early period in the media spotlight in the US, Li doesn’t actively court new investors, having found a steady stream of high-net-worth individuals and pension funds to back Himalaya. Many of them gather in Omaha every year for the Berkshire Hathaway general meeting, the ultimate gathering of value investors. Much of Li’s personal wealth is tied up in the fund. Its defining bet remains its investment in BYD.

Li prefers solitude over crowds, these days. Those who know him say he has a voracious appetite for reading. He doesn’t like taking meetings in the morning, preferring to save that time for absorbing company reports and financial news. From his office, lined floor to ceiling with books, he calls analysts for one-on-one meetings to discuss investment ideas. “We joke that Himalaya is an academic institution, where Li Lu is the professor, I’m the teaching assistant and the analysts are the students,” says Chang.

Recently, as relations with the US have deteriorated, it has grown more difficult for Wall Street to advocate for closer ties with China. Some large US endowment and pension funds are downsizing or divesting entirely from the country. Top executives at many of the US’s biggest companies have sleepless nights thinking about how to manage through the tension. BYD doesn’t sell its passenger cars in the US for political reasons. Three decades after student activists, including Li, lobbied for the US to cut ties with the country, a partial decoupling is taking place. Li’s last visit to China took place in 2019, just before the pandemic began.

Those close to his thinking argue, however, that the two countries’ fates are more intertwined than ever. When news of Covid-19 first emerged from Wuhan, Li mobilised his connections on both sides of the Pacific. Initially, he sent medical supplies from the US to China and then shepherded deals for BYD to sell face masks in the US. Millions of American shoppers who picked them up off the shelf at Costco became more familiar with BYD’s circular logo as a medical brand than as a car company.

In the office, Li started hosting team lunches over video daily, says Caroline Kim, Himalaya’s head of investor relations. “He was so concerned about the employees, a lot of whom don’t have family in the US. It feels very much like a family.” Later, Li co-founded the Asian American Foundation, raising $1.1bn to counter an outpouring of anti-Asian racism in the wake of the pandemic.

Now 57, Li has been in the US for over half his life and an American citizen for nearly 30 years. He has described himself as both 100 per cent American and 100 per cent Chinese. He owns cowboy boots and is fond of talking about the American dream that made him wealthy. Yet it would be absurd to compare Li’s journey with that of most immigrants, both for the historic circumstance in which it began and where it ultimately took him. With his employees, Li does not talk about the past much. It is “a very small part of his personal history”, says Chang.

In his autobiography, Li wrote that he and his fellow revolutionaries pledged they would meet again in Tiananmen Square 50 years after the movement. “We would bring out grandchildren and our diaries to show each other,” he wrote. But if that band of exiled revolutionaries, including Wang Dan, Wang Juntao and Chai Ling, sought to make good on that promise today, only Li would be able to set foot on Chinese soil easily. Who did Li Lu have to become in order for that to be the case? He told the National Museum of American History for an oral history project in 2016. “I am a survivor,” he said.

Eleanor Olcott is the FT’s China technology correspondent

Follow @FTMag to find out about our latest stories first

Read the full article here