Abdulrazak Gurnah was so surprised to win the Nobel Prize in Literature two years ago that, when the Swedish academy called him at his Canterbury home — where he was making a quintessentially English cup of tea — he thought it was a hoax. In subsequent interviews, the Zanzibar-born retired professor, who has spent more than 50 years of his adult life in Britain, has been scrupulously modest.

“I can think of several people who are more deserving. You can come up with 10 or 15 names,” he says during our lunch in a pub-cum-restaurant near Canterbury, although he won’t be drawn on who. “I can’t answer that. I’d upset too many people.”

Gurnah makes no secret of his delight at the prize. Since the phone call in October 2021, several of his out-of-print novels are suddenly on the shelves again. There are 10 in all, as well as short stories and essays. Numerous translations have been published, including in Mandarin and, perhaps ironically, in his native Kiswahili, opening his work to new audiences, Zanzibaris among them.

“It’s brilliant,” he says of the Nobel, with a twinkle at his good fortune. “I’d recommend it.”

In truth, the prize is richly deserved. Gurnah is a master storyteller and a lyrical, if piercing, chronicler of lives lived in forgotten and violent corners of European empires. From his first novel, Memory of Departure (1987), to his most recent, Afterlives (2020), he also charts the immigrant experience, both the rupture of leaving and the shock of arrival. He understands the motives of “absolutely brilliant, agile, energetic African young men, as well as their families, who want to come to Europe” even as he mourns a life left behind.

Whether he is conjuring a chilly English seaside boarding house or an East German city, his writing drifts ineluctably back to Zanzibar. “We think we’re learning or understanding or travelling, but really we’re like fowl tied to a stick fixed in the ground,” he says of his powerlessness to resist the pull.

Sometimes he forces himself to write about elsewhere. “You can say ‘OK, now I’m gonna try and break this and move to something else.’ But sooner or later, it’s, ‘Oh. Where am I? Zanzibar.’”

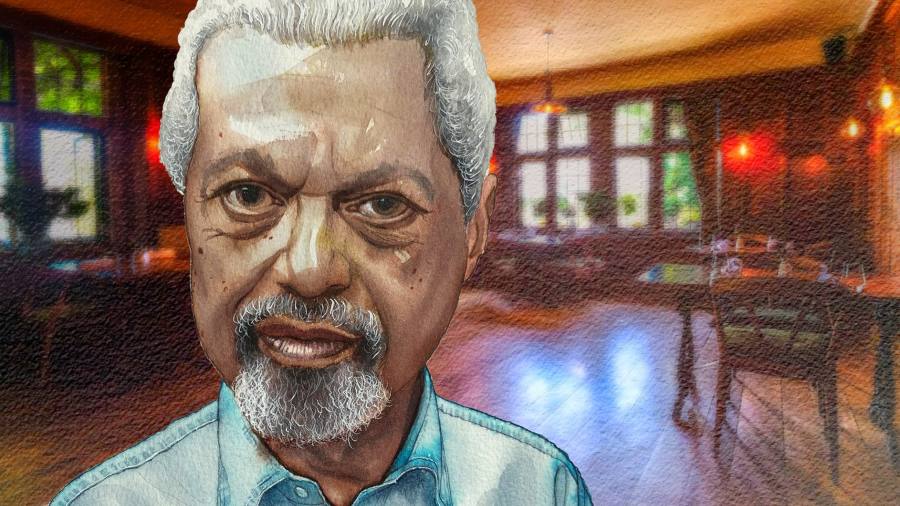

When I arrive at the Fordwich Arms, an old brick pub by a shimmering river, Gurnah is already installed in one of the plush green booths. He has a glass of white wine in front of him. There’s something of the still-life about the picture: the casually but immaculately dressed 74-year-old professor in short-sleeve shirt with trimmed white beard, twinkling glassware and summer light dancing in the translucent liquid.

On inquiry, it turns out to be an excellent Sancerre from Sylvain Bailly. I had intended to abstain, but my resolve falters and I join him for what turns out to be more than a single glass.

From the name of the Fordwich Arms, I had been expecting pub fare and was braced for sausages and mash. I’m pleasantly surprised to learn that it has been upgraded to a Michelin-starred restaurant. “I reckon it’s the best restaurant in Canterbury,” says Gurnah, adding somewhat tartly, “which is not to say a great deal.”

There’s an option for a tasting course but it’s all too elaborate. “No we won’t go there,” Gurnah says decisively. In the end, he orders turbot, with another glass of Sancerre in lieu of a starter. I opt for scallop followed by the turbot.

The other advantage of this place, he says, is that it is 15 minutes from his home in the neighbouring village of Sturry, where he lives with his wife, the Guyanese-born scholar of literature, Denise de Caires Narain. “So I can walk home after our lunch.”

Further discussion of his private life is curtailed. “Can we not talk about this? I like my life to be my own.”

The setting is all very English, yet Gurnah has been celebrated as an African writer. “When I was awarded this wonderful prize, people said who is he? Where does he come from? Is he this, or is he that?”

An FT headline had described him as Tanzanian. Was that the right thing to do, I ask, of a man who has spent five-sevenths of his life in Britain and who possesses a British, rather than a Tanzanian, passport? Besides, Tanzania, into which Zanzibar was incorporated in 1964, does not allow dual citizenship. Perhaps the FT should have celebrated him as another British laureate?

“I never said no,” he replies.

But we didn’t. Were we wrong?

“I don’t really know how to answer that. It’s not up to me. But it would have been fine if you’d have said, ‘Hey, one of our boys has won the prize’.”

He was brought up in the old port city of Stone Town. Zanzibar had been an overseas territory of Oman from 1698 when Omani soldiers defeated the Portuguese in Mombasa and for centuries it had been a babble of languages and influences.

From his house he could see the harbour master’s flag proclaiming the arrival of dhow sailing ships on the seasonal musim winds. Boats carried dried fish, nuts, dates, cloves and perfume from Pakistan and Iran. Karachi and Bombay seemed closer than Paris or London, although the presence of the British, including soldiers parading in their bearskin hats, left no doubt as to who was in charge.

The winds linked Zanzibar with other cities along the Swahili coast from Lamu, Malindi and Mombasa in Kenya, to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and Sofala in modern-day Mozambique. His mother was from Mombasa and his father from Yemen.

A waitress returns with snacks in various boxes, elaborately presented and with descriptions to match.

“We know that the earliest Muslim presence was probably on a small island called Manda, which is just off Lamu. They reckon that was maybe the ninth century,” he says. Shards of Thai pottery from even earlier and of Chinese pots from Admiral Zheng He’s 15th-century expeditions still litter the coast. “There was a pattern of trade which goes back way beyond what we know.”

Zanzibar had also been the hub of a much grimmer trade — in African slaves. In Paradise, Gurnah’s 1994 novel, which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, a young boy, sold by his father into indentured labour, goes unwittingly on a slave-trading expedition into Africa’s interior. From Zanzibar, enslaved people, often women, were sold to traders from India, the Middle East and even Indonesia. Later there was trade to the plantation islands of Madagascar, Mauritius and Reunion, and as far away as Brazil.

Gurnah grew up in the decolonisation period and remembers the excitement of rallies calling for the expulsion of the British. When they finally did leave Zanzibar in 1963, the island erupted in a revolution to remove the sultanate. Many of the Arabs who had lived in Zanzibar for generations were killed, imprisoned or expelled. Property and business, including that of Gurnah’s father and uncle, was expropriated.

“It all became incredibly violent and racist,” says Gurnah, his voice quivering with what are still evidently traumatic events. “It didn’t have to be quite as cruel as it was. But it was. And when these things are out of control they’re out of control.”

Eventually schools were closed. At 18, Gurnah saw no option but to leave. “I just thought, something better than this is possible.”

He acquired false documents and flew via Dar es Salaam to England, having borrowed the £400 necessary to present himself as a tourist. His cousin was studying for a PhD in agriculture at a campus outside Canterbury, so that’s where Gurnah ended up.

Several of his characters, including the boy in Paradise who bids farewell to his mother with barely a word, fail to realise the momentous implication of departure. So did Gurnah.

“I remember waking up because we arrived late at night thinking, ‘What am I doing here?’” he recalls of his first night in Britain. “‘Why are we here? I don’t know anything about this place.’”

Having left Zanzibar illegally, there was no possibility of return. Thus began what he calls “a prolonged period of poverty and alienation” in a country whose people frequently made him feel unwelcome. There was the constant background hum of racism. Once he’d started university, he would enter the classroom to find pictures of cannibals chalked on the board.

Years of slog would eventually take him, via a PhD and a stint of teaching in Nigeria, to a position lecturing in English and postcolonial literature at the University of Kent.

While I’m eating my scallop, served in the shell in a delicate broth, he tells me about his early years in England. He threw himself into reading. In Zanzibar, he had been brought up first on the Koran and then on abridged versions of books such as Robinson Crusoe or One Thousand and One Nights, often in Kiswahili. English was very much a second language.

In England, by contrast, books were everywhere. “I really read every damn thing I could find,” from Saul Bellow, James Baldwin and Herman Melville to Tolstoy and Stendhal. Later, because he taught them, he read the English classics, starting with Hardy and Dickens.

He also began to write. At first this was a private act of therapy, a way of reconnecting with the lost world of Zanzibar. But gradually he began to fictionalise events and, after many drafts and false starts, his first novel took shape. It was published 20 years after his arrival in Britain.

Loyal editors and fans kept him going. The former indulged him. He insisted, for example, that words from Kiswahili, German or Arabic, which dot his prose, should not be italicised. “It was a response to perhaps an over-energetic desire from editors to put every word they didn’t know in italics. But it’s not foreign in the context. So let me use italics when I want emphasis and not to say, ‘This is a foreign word’,” he explains. “To my astonishment, they let me do it.”

Our main course arrives. “You have the south coast, line-caught turbot,” begins the waitress, presenting cowboy-hat-sized plates with tiny portions of snow-white fish. There’s something that sounds like a “chap on a plate” (I don’t dare ask for clarification) and “some tempura battered belly”, which turns out, indeed, to be the belly of the fish.

“Do you have to spend hours learning that,” Gurnah asks.

“It’s a sort of learn-as-you-go type situation, or make-it-up-as-you-go,” the waitress deadpans. Then, more seriously: “We have a whiteboard.”

The elaborate descriptions notwithstanding, the cooking expertly brings out the natural flavours and succulence of the fish.

Since his first novel, Gurnah has produced a steady stream of others. He has compared his writing to the activity of a gardener, coaxing and arranging words. Does he feel as though he has perfected his craft? Not at all, he says. “All the time, you work at it, work at it, work at it.”

He retired from teaching in 2017, but remains emeritus professor. “It’s just a polite way of saying you can have access to the library.”

Ironically, the Nobel Prize has stopped him from writing. Since its announcement his life has been a blur of travel and promotion. This month he will finally get back to the novel he had started when the Swedish Academy came calling.

We pass on dessert. I suggest coffee, but Gurnah has developed a taste for the Sancerre — as have I. “Do you think I could stretch your budget to another?” he says, waving an empty glass. “We should have ordered a bottle.”

Our talk turns to immigration, which has become an issue in Britain as people cross the Channel in small boats from France. “Only now are you experiencing the presence of these people in this terrified way, enough to allow governments to act with this kind of inhumanity — like these barges,” he says, referring to a recent government decision to house immigrants on floating accommodation.

He finds it ironic that a government willing to do what he calls “these cruel things” is led by people, including Rishi Sunak, the prime minister, Priti Patel, the former home secretary, and Suella Braverman, her replacement, whose families have a recent experience of immigration. In some cases, “their very parents were people who had to leave rather suddenly from dangerous places,” he says. “I can’t understand, really, how they forget that.”

What would a humane policy look like, I ask. “Well I don’t know. If I did know I would be running for parliament,” he parries. But he favours more legal routes. “There has to be a process. Now there is no process and therefore the only way to do it is to risk your life.”

He writes poignantly about the sadness of crossing continents. One of his protagonists, a shop owner from Zanzibar, arrives at Gatwick airport to seek asylum. He has taken another man’s name and pretends to speak not a word of English. By the time the immigration official confiscates his one memory of home — a fine box of incense — he has been stripped of everything that made him who he was.

The fictional immigration official, Kevin Edelman, is the son of a Romanian, but doesn’t consider himself to be an immigrant. He is modelled on Michael Howard, the then hardline UK home secretary, whose father was also Romanian. “I thought it must be that if you are a European you can’t feel that you’re an immigrant. That’s the narrative I guess of Edelman,” he says. “He’s not black.”

The mass movement of people from the “global south” northwards, a relatively recent reversal of a 400-year-old pattern that saw Europeans heading south, is what he calls “the phenomenon of our age”. I quote a line I had jotted down from By the Sea: “The same gate which had released horses that went out to consume the world and to which we have come sliming up to beg admittance.”

“There’s a better one. We are here because you were there,” he says. “The intervention of Europe into all these places doesn’t just stop. It continues in various ways. It continues with the havoc left behind, but it also continues with those who have been carried away by it, or seduced by it.”

Weren’t you one of those people, I ask.

“Well I came here because I wanted to make a new life for myself. Then what I realised, which I hadn’t realised before, is that having done that I had no other place to go. So, then I learned to love Britain.”

David Pilling is the FT’s Africa editor

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on X

Read the full article here