Jon Hillis has always been community minded. As a child, he was an avid Scout, rising to a senior national role, and it was Reddit boards and Science Olympiad discussions that helped him find pals as an awkward teen. After college, he briefly founded and ran Discoverboard, a subscription-based site much like a forerunner of Discord; the start-up’s goal was to foster smart, long-form conversations.

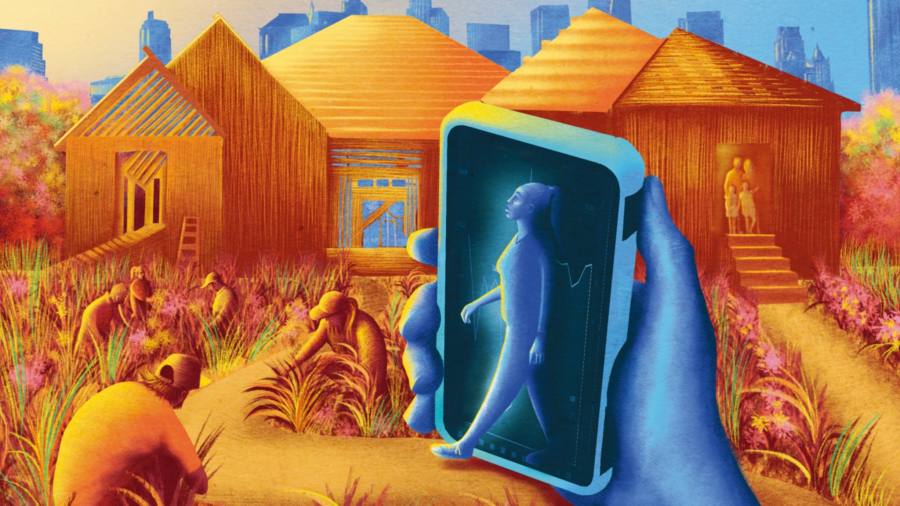

Now aged 31, Hillis has taken that community-building instinct offline via Cabin, an organisation that aims to bring the concept of a kibbutz into the broadband era.

He lives at one of the properties in its network, dubbed Neighborhood Zero, in Texas Hill Country just outside Austin. It was the first in the network and emerged from a property he had inherited from his grandmother; Hillis formally launched it in May 2021. The impetus was simple: “Bringing out great people from the internet to get together and co-create,” he says.

Initially, it was an impromptu gathering but it soon developed into a bigger, longer-term idea. Could he turn part of the 50-acre plot into a true community, where others with similar goals, values and interests could live? To find out, Hillis installed a four-bedroom shipping container kitted out as a co-living cabin, and added bathhouses, an outdoor gym, saunas, cold plunge pools and more.

The idea, he hoped, was to reinvent the concept of a community. After attracting a dozen or so like-minded people, he was encouraged that others might want to follow his lead.

In Cabin, Hillis wanted to deploy new digital technologies to help decentralise government and return power to the residents — think decision-making by committee, using blockchain technology to vote and verify membership (or citizenship, as he calls it).

His development for the like-minded is an example of a revived phenomenon, one that sees groups of people coalesce physically, living together much as they might cluster online in a Facebook group or on a Reddit board. How and why these communities are coming into being is an intriguing question driven by financial, cultural and geographical trends.

People can live in, and work from, Neighborhood Zero in several ways: they can invest or they can participate in what Hillis calls “definancialised workstays”, where labour on the project is offered in exchange for room and board and, potentially, eventual citizenship. In this way, he hopes to bring a broader group together than simply well-to-do, well-meaning people.

Once he had started on Neighborhood Zero, Hillis set out to build a community of these communities, and soon sent out word he wanted to create a co-living network that could co-operate — offering, for example, reciprocal residency rights like a private members’ club. He has now established links with more than 20 such settlements in the US.

“One of the magical parts of building an internet-native community — the right people just show up when you put out a bat signal,” Hillis says. “People who are excited about building new ways of living are drawn to it.”

The trend for community building is re-emerging elsewhere, too. Hillis is focused entirely on rural areas — “right now, the thing we can uniquely provide is a high density of great people in a natural setting” — but others are attempting to import his approach to big cities.

In Brooklyn, one couple, Andrew and Priya Rose, spent months identifying and crowdsourcing the best place for them to encourage a stealth move-in en masse, allowing their peers to transform it into a private mecca. On the Substack account where they tout the idea of what they have called Fractal to potential fellow residents, they say the ethos of their work is to combine “the serendipity of a college campus, the co-creation of Burning Man, the agency of Silicon Valley, the vigour of a Midwestern high school track coach and the culture of New York City”.

Having settled on a slightly windblown corner of Brooklyn, the group’s leaders are working to encourage more move-ins. “Living in community has been the overwhelmingly cultural norm for all of human history, and is a necessary component of human happiness and health in an otherwise isolating culture,” Priya Rose told the FT.

Another project is touting a similar return to that purported norm, this time in San Francisco; known as the Neighborhood SF, it’s planning to build a community around Alamo Square Park near the Painted Ladies colourful period houses. Neither of the areas is among those respective cities’ priciest but such efforts will still require significant financial investment to achieve their aims.

Meanwhile, on Zanzibar’s main island, Unguja, the Liberty Places project is under way. It’s an entirely different self-defined community from these but with much the same underlying impulses.

The first funder was Mike Yeadon, a British former Pfizer executive who became wealthy after selling his biotech company. He’s also an ardent Covid-19 vaccine sceptic. And, via Liberty Places, Yeadon and his ilk want like-minded folks — think anyone with a cherry blossom on their social media handle (an emoji often used by anti-vax groups) — the chance to come together, unvaccinated and unjudged. Liberty Places declined to comment on this story.

The two-year-old Liberty Places has announced plans to work with Passivhaus architect Sean Clifton to develop sustainable homes there. Like Cabin, blockchain technology will help create a transparent digital economy in its jab-free Eden.

Blockchain is also the foundation for so-called Crypto Rico on Puerto Rico. Bitcoin acolytes have flocked there in the past two years, swapping tips and advice, often living together in some of the wealthier gated communities. The ringmaster for those keen to leverage such benefits is former child actor and crypto poster boy Brock Pierce, who also ran for US president on an independent ticket in 2020.

Pierce says he came here to set up a bank in late 2013 and has become an evangelist for would-be internal expats. He has even tried to corral funding to create a standalone capital for Crypto Rico. “One of the ideas was to build the smart city of the future here, to see if we could buy a big chunk of the old naval base so that, instead of being a symbol of the military-industrial complex, it could be a symbol of the future.”

It has not progressed past the concept stage but Pierce is undaunted. “Rome wasn’t built in a day — it’s a long process,” he says.

What drives the impulse for such niche utopianism? Though many adherents now suggest a mould-breaking mindset, anthropologist Setha Low draws direct comparisons to an unlikely forebear: the gated community. Low is a professor at City University of New York, with a speciality in environmental psychology, and is the author of Why Public Space Matters.

Despite their idealistic overlays, she sees these settlements as new iterations of that idea, which gained popularity in its current form in the US from the 1960s. The older developments lacked the ideology that helps Liberty Places and the like to cohere; rather, they thrived by allowing municipalities to shift the cost of expanding housing in unincorporated land on to developers.

These companies would create both homes and infrastructure at no cost to the city; new residents who moved in would then increase the annual tax base, bolstering its coffers as a result. Still, once someone lives in a like-minded community with a sense of separation from the world, groupthink will emerge.

“The gating ideology develops once you live there,” Low says. “And the kind of interiority we see developing now exaggerates being with like-minded people and rejects diversity.”

Why should such ideas re-emerge now? One theory is that rising rents and mortgage rates have created instability and uncertainty around traditional housing. Collective living, with the peer support it implies, including sharing overheads, could offer affordable security.

These new communities are conceptually borrowing from lower-income social housing. “But they’re taking that model and applying it in an antisocial way — it’s maybe the aesthetics of pro-social and the economics of antisocial,” says Samuel Stein, author of Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State.

“They’re shutting out the outside world: let’s create our own universe, live in it and thrive and we won’t have to worry about what other people will say.”

There is a cult-like aspect to such gatherings, says Janja Lalich, a researcher with a speciality in extremist groups who spent several years as a member of a cult in the 1970s.

“It’s a basic human trait to want to belong and to have purpose but, with everything that’s going on in our society, not knowing what’s going to happen next, people think they’d better sign up with some people to be protected. They think: ‘Yeah, I’ll be a little isolated, but that’s the best way to be safe right now.’” There’s a superiority implicit in membership, too, she adds, in being convinced you’re on the right path.

Proponents of these new communities reject comparisons with cult-like settlements, however, emphasising that there is no requirement, explicit or implicit, to conform to any given parameters. These are bridging rather than bonding communities, intended to bring a disparate but compatible group together rather than to coalesce groupthinkers.

Fractal’s Priya Rose points to a recent Substack post published by her husband, “Avoiding Cultification: A Comprehensive Guide”.

“It’s not a cult,” she adds. “It’s literally just a bunch of friends trying to live near each other and work on creative projects together.”

Yet qualms around cultish elitism connect with another potential consequence of such communities: gentrification. Efforts often focus on locations where property is cheap enough to move in as a large group. In New York, for instance, Fractal identified a tranche of Brooklyn where the average monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment is $3,850, according to Renthop; in nearby Greenpoint it is $4,495.

Advocates for the idea counter that other issues have greater impact on gentrification — the general lack of housing supply, for example.

Boston-based urban geographer Loretta Lees has researched self-created communities around the world. She notes that the efforts of founders can be simultaneously productive and destructive, especially when carving out a district within a wider city.

“They’re trying to create this techie hippie Friends sitcom-type community,” she says of efforts such as Fractal in New York. “But they both want to be part of the city and not — they’ve already talked about putting in ‘stop’ signs on the streets . . . and that’s just suburbanising.”

Priya Rose disagrees. “We don’t want to live alone in the suburbs,” she says. “Living in community is a rational, cultural response to an absurd housing scarcity and a loneliness epidemic.”

Greg Lindsay is a senior fellow of NewCities, a Canadian urban planning non-profit. Of self-created communities, he says: “They’re overly utopian, and it’s about community management, who are the glue figures.”

Back in Texas, Jon Hillis sees things differently. He says social organisations, such as Elks and Rotary clubs, declined in the US in the late 20th century, leaving a few outliers still in operation, such as college fraternities and sororities. He doesn’t want to replicate the hazing or harshness that can take place in such groups but he is happy to re-energise their sense of social cohesion.

Unlike gated communities, he adds, Cabin is more inclusive, as it allows anyone to join — whether using their money or their muscle.

“You need a barrier — you can’t say anyone from the internet can show up anywhere any time but there’s no single gatekeeper in our community, any member can vouch for another person” if they want to join, Hillis says.

The next stage for Cabin’s team: creating a consulting arm to help those interested in starting from scratch, steering them in a co-buying programme, where individuals can pool resources to follow his lead. Hillis is yet to launch it as he is still workshopping individual elements. What is clear is that they will share a simple, three-pronged ideology.

“Fast internet, access to nature and a strong community — those are the core things that make for a Cabin neighbourhood,” he says. When you put it that way, it’s hard to entirely deny its appeal.

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram

Read the full article here