Receive free War in Ukraine updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest War in Ukraine news every morning.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has described the Soviet invasion of Hungary and Czechoslovakia as a “mistake” that harmed other nations, even as he continued to defend his war in Ukraine.

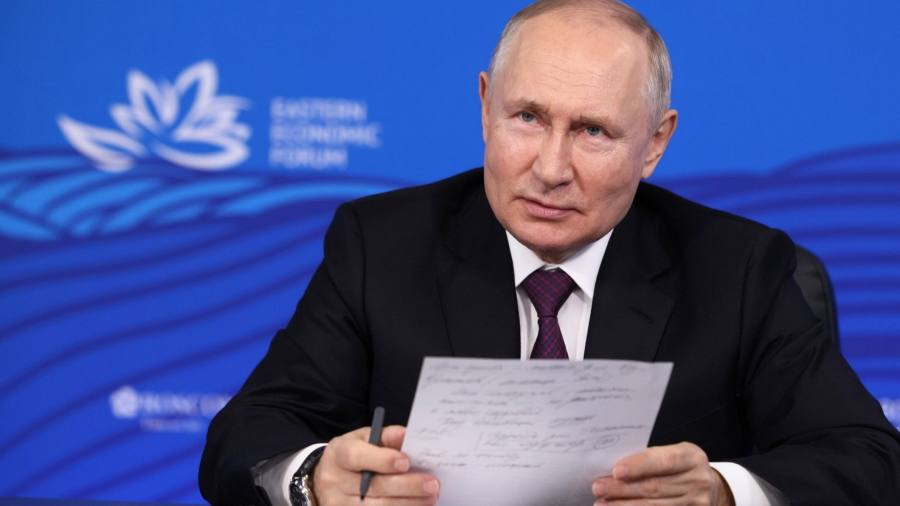

“This aspect of Soviet Union policy was wrong and only fuelled tensions,” Putin said during a panel session at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok on Tuesday. “It is not right to do anything in foreign policy that is in direct conflict with the interests of other nations.”

His remarks, while glossing over Moscow’s ongoing aggression against Kyiv, were aimed at extending an olive branch to central and eastern European countries where politicians have espoused more sympathetic views towards Russia than their western allies.

Putin had previously described the collapse of the Soviet Union as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century”. But on Tuesday, he offered a more nuanced view in response to a question about whether the Soviet Union behaved “like a colonial power” when it sent tanks to Prague and Budapest to quell pro-democracy protests.

Mass demonstrations were brutally repressed in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, resulting in the loss of at least 2,600 Hungarian lives and about 140 Czechs and Slovaks.

Even though Putin did not directly compare the Soviet actions to his invasion of Ukraine, he has built a different narrative around what he calls Russia’s ‘special military operation’ in the neighbouring country.

“It’s crucial for Putin to highlight a fundamental distinction between Soviet invasions of eastern bloc nations and the intervention in Ukraine,” said Andrei Kolesnikov, a senior fellow at Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. “While the Soviet Union was wrong, Russia now seeks to reclaim what it believes is rightfully its own, thereby restoring justice.”

Kolesnikov described Putin’s statement as a “verbal ploy” intended to demonstrate the lack of imperial ambitions. “Putin is well aware that he will never be able to bring the eastern bloc back into his sphere of influence,” he said, so why not make this gesture.

In Slovakia, Putin’s comments come at a time when some pro-Russia parties are campaigning ahead of general elections on September 30. Former prime minister Robert Fico, who leads the race, has called for an end to military aid to Ukraine while smaller Slovak parties such as Republika are demanding the lifting of sanctions against Russia.

Putin’s new stance on the Soviet Union was “quite surprising”, said Tomáš Strážay, director of the Slovak Foreign Policy Association, a think-tank in Bratislava. “This was said on purpose for a wider audience outside Russia, perhaps not only for political leaders in Slovakia and Hungary but for anybody in the western world who thinks there is still a possible dialogue with him and Russia.”

In the context of the upcoming Slovak elections, Strážay said Putin’s remarks could be used by pro-Russia politicians to claim he “isn’t such a bad guy after all”.

In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán is a longstanding Putin ally and has repeatedly staggered the adoption of EU sanctions and refused to send military aid to Ukraine.

Putin’s admission about the Soviet mistake in quashing pro-democracy protests in Budapest can be seen as a “diplomatic gesture, but hardly more than that”, said Péter Krekó, a director at the Political Capital institute in Budapest.

A new high school history textbook written by one of Putin’s advisers drew criticism both in Russia and abroad when it claimed that the 1956 Hungarian Revolution was a fascist uprising organised by the west and that the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Hungary in 1990 was a mistake.

“This sort of ambivalence, calling 1956 fascist while saying it was a mistake to crush it, has always been a part of Russian diplomacy,” Krekó said.

“If everything and the opposite is said, you can do anything because what you said can’t be held against you. This is a feature, not a bug,” Krekó added.

Over the past decade, Putin has moved to restore the memory of the Soviet Union as part of his effort to develop unifying Russian “spiritual bonds” and “traditional values”.

Although Putin spoke at an economic forum, he devoted a significant amount of time to his favourite topics, such as discussing the colonial past and what he perceives as the new colonial policies of the west.

Carnegie’s Kolesnikov said: “Putin repeatedly underscores that Russia has never engaged in colonialism, despite Russia’s historical record, which includes various forms of colonisation. Otherwise, the Russian empire would not have developed as it did.”

Read the full article here