Receive free Education updates

We’ll send you a myFT Daily Digest email rounding up the latest Education news every morning.

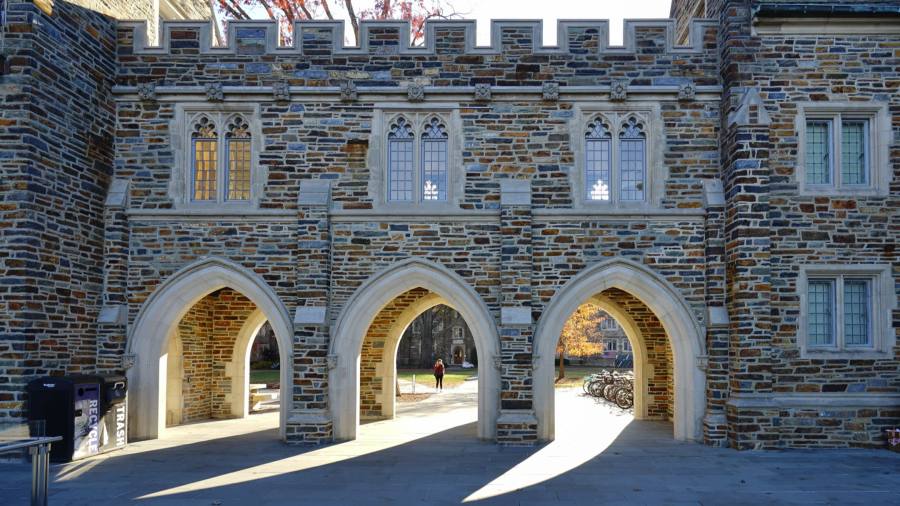

Duke University is finalising a probe into one of its most high-profile professors, sparked by concerns over his own research into dishonesty including a study claiming people were more honest after first being given a “moral reminder”.

Dan Ariely — a behavioural scientist who has written several best-selling books, advised companies and inspired the fictionalised NBC series The Irrational launching next month — co-wrote “The Dishonesty of Honest People”, a widely quoted 2008 paper that found students asked to recall the Ten Commandments were less likely to cheat in a survey.

He has denied any falsification, but others have questioned the research. A group of academics in different countries reported in 2018 they were unable to replicate his findings. Bruno Verschuere at Amsterdam university who led the attempts, told the Financial Times: “I think there is reason for retraction. Given the many uncertainties about the original methodology and the source of the data, how can we put trust in the findings?”

The Duke investigation is the latest in a growing series of probes of academic practice, including an inquiry by Stanford University released last month, which led to the resignation of its president, and another by Harvard University, which requested three retractions of papers written by one of its business school professors and other authors.

The Stanford probe did not find evidence that Professor Marc Tessier-Lavigne manipulated any findings, but he was criticised for failures in oversight and management of his team and for not acting decisively to correct errors in papers brought to his attention.

Prof Francesca Gino this week sued Harvard and Data Colada, the blog that criticised her studies on dishonesty, accusing them of defamation and seeking $25mn in damages. She said in a statement: “I have never, ever falsified data or engaged in research misconduct of any kind.”

The nuances in those two cases highlight the difficulties for external critics, and even academics’ own universities, in investigating the circumstances around studies they later question. Research such as Gino’s and Ariely’s was conducted more than a decade ago and used data apparently originally collected in written rather than electronic form.

Ariely and his co-authors retracted a separate 2012 paper after agreeing with the Data Colada blog that responses in two of the underlying studies they drew on had been falsified, but each said they had not been responsible nor were aware of any manipulation at the time.

The retraction undermined their original findings that those who signed a declaration at the start of a tax form and a car insurance company claims audit were more honest.

The Hartford, the insurer involved, told National Public Radio last week that the data it provided to Ariely was substantively different from that described in his published study. “There were significant changes to the size, shape and characteristics of our data after we provided it, and without our knowledge or consent,” it said.

Ariely told the FT: “It is unclear and of course very frustrating that we do not know how the data was falsified. What I know for sure is that I never did, nor ever would, falsify data.”

He said he also stood by his findings in the 2008 Ten Commandments research, which has not been retracted and which he said had since been confirmed in new research currently being peer-reviewed. He said the underlying data used in the original study was provided to him by the University of California Los Angeles in 2004.

But Prof Aimee Drolet Rossi at UCLA Anderson said the study he described was too complex to have been one of the surveys she oversaw at the time. She said his description of the way the study was carried out, the incentives paid and the number of participants differed from those taking place at her department.

Duke has refused to comment on its investigation into Ariely’s work, but Rossi shared emails with the FT confirming that in 2021 she was in touch with the university officials examining concerns around his work, including on the Ten Commandments study. Another individual with knowledge of the probe said findings from the investigation have been drafted and are being reviewed.

Ariely said: “While I can’t comment on the process, I am confident in Duke, as a leading academic institution, its people and their comprehensive process and professional review. I stand by my work.”

His research has been subject to criticism from other academics, including Richard Thaler, the Nobel Prize-winning behavioural economist at University of Chicago.

Remy Levin, a behavioural scientist at Connecticut university, said: “As a scientist, it is Prof Ariely’s duty to ensure that his scientific record is free of errors and falsehoods. The burden of proof lies with him to show to the scientific community and the public at large that he has told the truth about his work.”

Read the full article here