As we near the end of what has historically been the worst performing two months of the year for the stock market, and the pullback intensifies, the chorus of warnings from the bear camp grows louder. The economic data is perceived to be either too hot, suggesting interest rates will stay higher for longer, or too cold, raising concerns about a recession in the months ahead. I think the reality is that the data in aggregate is just right, continuing to trend in the direction of a soft landing for the US economy in 2024. While there were virtually zero expectations for that outcome at the beginning of this year, a growing consensus of economists on Wall Street now see it as a distinct possibility.

Edward Jones

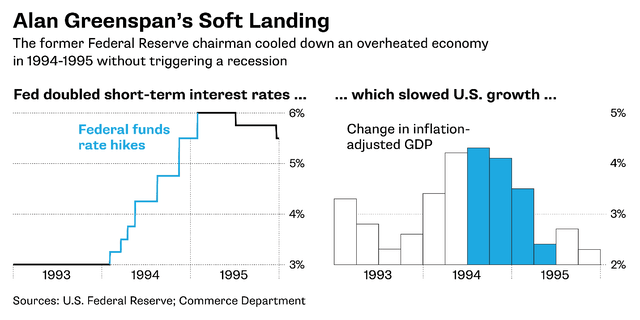

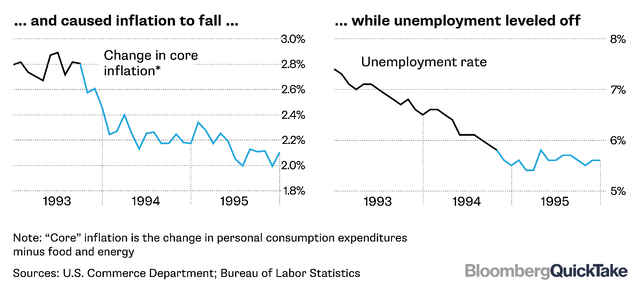

A soft landing will occur if the Federal Reserve succeeds in slowing the rate of economic growth, primarily though increasing borrowing costs with higher interest rates, to the extent that the rate of inflation falls to its target of 2%. The other side of the equation is that it must avoid stifling the rate of economic growth too much, and increasing the unemployment rate to such a degree that it causes a recession, which is defined as two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. The reason there have been so many doubts about the potential for a soft landing is that they do not happen very often. Arguably, the last one to occur was in 1995 when Chairman Greenspan doubled short-term interest rates from 3% to 6% in an effort to slow an overheating economy.

Bloomberg

That cooled the rate of inflation from nearly 3% to the Fed’s target of 2% without seeing a meaningful increase in the unemployment rate.

Bloomberg

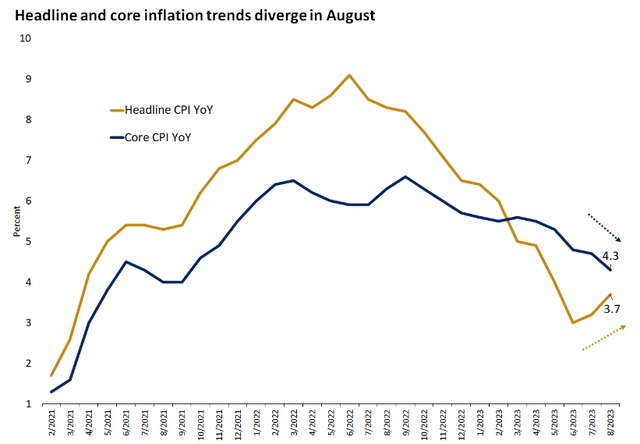

Chairman Powell has been faced with a far more formidable task, considering that the rate of inflation rose to more than 9% last summer, forcing the Fed to raise short-term rates from near zero to 5.25%. The rate of economic growth has slowed to approximately 2% over the past year, while the unemployment rate has risen from a multi-decade low of 3.4% to 3.8%. Impressively, the rate of inflation has fallen as low as 3.2% before rising more recently to 3.7%, due entirely to the spike in oil prices, which I do not think is sustainable in a slowing-growth environment. The core rate, which is the Fed’s primary focus, should continue to decline, as wage gains and shelter costs keep easing over the coming months.

Edward Jones

The naysayers claim that the rise in oil prices will continue and spread throughout the economy, forcing the Fed to raise interest rates more, or at least hold them high for longer, to sap demand further. Yet this assumes that the increase in oil prices is demand related when it is not. The recent spike is due to supply cuts from Saudi Arabia and Russia, which has fueled speculative demand for oil futures contracts. That can shift on a dime, and it probably will because sluggish growth in China and softer growth rates globally are not likely to support $90-plus oil for long. The Fed has no control over this, which is why it focuses on the core rate.

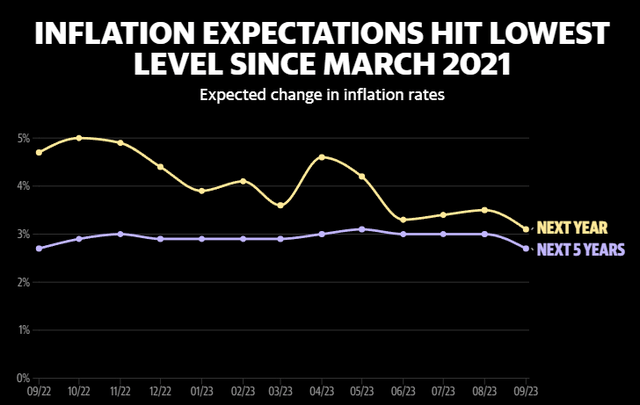

More importantly, the Fed focuses on inflation expectations, and there was more good news on that front last week from the University of Michigan in its Survey of Consumers. Americans see inflation averaging 3.1% over the next year, which is down from 3.5% last month and the lowest reading in two and a half years. The five-year expectation fell from 3% to 2.7% This is notable progress for the Fed.

YahooFinance

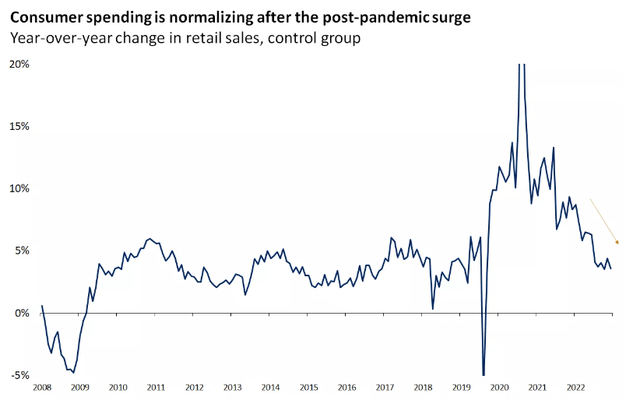

As the disinflationary trend continues, we also continue to see signs of economic resilience. Consumer spending growth is returning to pre-pandemic levels just as there are early signs of a recovery in manufacturing. The Empire State Manufacturing Index for September came in sharply higher than expected with expectations for future business conditions rising to its highest level in more than a year. I think this is a harbinger of things to come for the sector, which will be greatly needed as consumer spending on services starts to wane this fall.

Edward Jones

It is easy to poke holes in the narrative for a soft landing, because any individual incoming economic data point can be viewed as either too strong or too weak on a standalone basis. We must look at them in aggregate to see continued disinflation combined with a below-trend rate of economic growth that allows the Fed to start loosening its restrictive policy next year and returning its benchmark rate to a neutral level.

Read the full article here